Patrick O'Duffy's Blog, page 15

June 16, 2013

A hiatus in E minor

Hiya folks,

After much thought, I’ve decided to take a break from regular blogging for a while.

Come on, it’s not that bad, I promise.

It’s just that I have a lot on my plate now – day job, Raven’s Blood, some freelance editing, a semblance of a social life – and taking the time to write two posts a week is really eating into what I have left. (Especially as, despite all my sensible advice, winter weariness and SAD is kicking my butt right now.) Something’s gotta give, and for the next while it’s going to be the 2-3000 words I spend blogging every week.

That doesn’t mean no blogging at all, because having a platform for saying what I think (even if no-one’s listening) is more addictive than blue meth – so I’ll probably pop up now and then to spout off. But the usual two-posts-a-week schedule is getting retired for about, hmm, two months or so. Hopefully that’ll be enough time to really knock off a big chunk of the novel, get some other projects out of the way and build up a head of energy again for sharing my feelpinions.

Please. It’ll be okay. I’ll be back soon enough. Just like Dan Harmon.

June 13, 2013

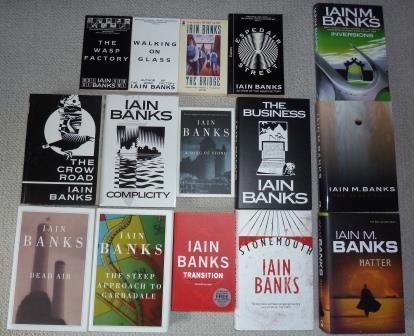

Remembering Iain Banks, 1954-2013

I don’t remember my past all that well, so I can’t put my finger on exactly when I read The Wasp Factory. It was written in 1984, when I was 13, but there’s no chance that anything so transgressive and disrespectful would have been in any libraries in my old home town. So it must have been after I moved to Brisbane, when I was 18 or 19. That sounds right, that feels right; that’s the right age for having Iain Banks blast out the back of your head for the first time.

At age 19 I also lived and breathed science fiction, so I imagine I would have immediately read Consider Phlebas, although that memory is still vague. I do recall reading The Player of Games and The Bridge at around age 20, and not liking either of them as much as the other two but still thinking they were pretty damn cool.

At age 19 I also lived and breathed science fiction, so I imagine I would have immediately read Consider Phlebas, although that memory is still vague. I do recall reading The Player of Games and The Bridge at around age 20, and not liking either of them as much as the other two but still thinking they were pretty damn cool.

Then I read The Crow Road and Use of Weapons as they were published, and that was it – I was an Iain Banks fan, whether he was writing mainstream or science fiction, whether he had an M in his name or not.

And now Iain Banks is dead, cut down by gall bladder cancer this last weekend, two too-short months after publicly announcing his illness.

–

Others have done fine duty eulogising Banks, such as Kieron Gillen and the UK Telegraph; io9 has a good essay on the lessons writers (especially SF writers) can take from his work. But I don’t want to eulogise and I don’t want to think like a writer; I want to think like a reader. My memories can be like fog, but when I think about Banks’ work I remember all that I got from his books as a young man.

I remember marvelling at the forward-backwards progression of Use of Weapons that spiralled into the horrific darkness at its heart.

I remember the final goodbye of The Crow Road and how I kept coming back to that book as my relationships came together and fell apart.

I remember reading the Eliot quotes in Consider Phlebas and thinking that I had to read more of this guy’s poetry at some point.

I remember cruising through three out of every four chapters in Feersum Endjinn and then grinding to a halt on the fourth, slowly working my way through the phonetic, accented prose – but being drawn in by that effort rather than thrown from the story.

I remember hitting that scene in The Wasp Factory and putting the book to one side, needing to walk it off for a while – and then coming back to see if he could top it. And he did.

I remember pressing his books on friends saying you’ve got to read this, and then them coming back saying holy crap, do you have any more of his stuff? And I did. I always did.

I remember my 20s in music, in beats, in dance floors – and in Banks novels, the prose soundtrack for my life.

And memories like that are all readers can ever hope to be granted by an author.

–

I didn’t like Banks’ later work as much as his earlier books; I started to drift away around the time of Look to Windward and Dead Air. But that was my fault, not his; I stopped resonating with the themes and ideas he wanted to talk about, and he was determined to write what he wanted rather than what I (or anyone else) wanted to read. To write honestly, and snarkily, and passionately about what he thought was important; about visions of the best and worst we could be.

He wrote as he would. He lived as he would. And we were fortunate for it.

But not any more.

He’s away the crow road now.

June 10, 2013

What writers can learn from filthy roleplayers

It’s been thirty years – holy crap, thirty years – since I found a copy of Basic D&D in the local gift shop. I’d seen ads for it in the back of X-Men comics and wanted to find out what it was, so I bought it with my birthday money and spent the next week trying to figure it out.

Now, after a hundred campaigns, a thousand sessions and about a million words in various sourcebooks, I still don’t know whether I’ve truly figured roleplaying games out. But I’ve enjoyed trying, and that’s the main thing.

Thirty years is also about how long I’ve been writing fiction, all the way back to my first SF story written at age 12 – and, setting the stage for my entire career, handed into my teacher long after it was due. So for me those two pursuits have run in parallel almost my whole life. My writing informs my gaming, mostly in how I approach plotting and in the language I use when GMing; listen to me run a game and you hear the same turns of phrase that pepper my fiction. But gaming has also informed my writing, because there’s a lot that writers can learn from playing and running games.

What you can’t learn from gaming, just to be clear, is how to write well – decades of gaming fiction have proven that. While there are rare writers who bring style and craft to gaming fiction, like Greg Stolze or Don Bassingthwaite, the vast majority of it is workmanlike at best and utterly dreadful at worst. Hell, Gary Gygax invented the whole damn hobby, but look at his Gord the Rogue books – or better yet, don’t, because they’re terrible. Really fucking terrible. Like a whole new level of terrible 1d6 layers below the regular terrible of other game novels and patrolled by wandering 3d8 awfuls all armed with +3 glaive-guisarmes of suck.

What you can’t learn from gaming, just to be clear, is how to write well – decades of gaming fiction have proven that. While there are rare writers who bring style and craft to gaming fiction, like Greg Stolze or Don Bassingthwaite, the vast majority of it is workmanlike at best and utterly dreadful at worst. Hell, Gary Gygax invented the whole damn hobby, but look at his Gord the Rogue books – or better yet, don’t, because they’re terrible. Really fucking terrible. Like a whole new level of terrible 1d6 layers below the regular terrible of other game novels and patrolled by wandering 3d8 awfuls all armed with +3 glaive-guisarmes of suck.

Well. Maybe not that much. But lord, they’re not good.

But what you can learn from roleplaying games – especially the new breed of drama-focused indie games (but also from plain ol’ D&D and its kin) - is how to tell a coherent, engaging story, along with a few tools that can carry across to telling stories in prose. And tonight, prompted by a suggestion by my mate Dan a while ago, I want to look at some of those things.

Distinctive characters…

One of the great challenges of gaming is reconciling the creative and aesthetic visions of everyone involved, and nowhere is that more apparent than when the players create their characters. But that process also ensures that each of the player characters comes from a different place and sensibility, making them distinct and unique, portrayed with different voices and styles – and equipped with distinct, different abilities. Run a session of a game, any game at all, and you’ll see those disparate ideas come together and find an equilibrium, one where each character is immediately identifiable and has a different set of tools for shaping play. This doesn’t mean you should outsource the creation of your novel’s characters to other people, of course; instead, focus on creating characters that aren’t all cut from the same mold, that have different priorities and purposes in their conception, their interactions with the story and what they can achieve.

…with meaningful abilities

The other good thing about character creation in RPGs is that it delineates what a character can actually do. In some games this is very rigidly and ‘realistically’ defined, outlining exactly how much a character can lift/learn/stab; in others it’s more narrative and handwavey, broadly outlining an archetype or describing the strength of their relationships. No matter the approach, though, all games find a way to define the things that are important in play and then shape the characters so that they interact with those things. This means that players produce characters that can attempt to solve conflicts in different ways and that those ways can all be useful and meaningful in some way. That’s an excellent set of priorities for fiction writing – make sure that the different things characters do all have some impact on the story, even if not in every scene, and that they align with the themes and motifs that you’re trying to define as important in the narrative.

Pacing

Oh god, there is nothing so important and vital I have learned from gaming as pacing, and I have learned it the hardest way possible – by boring the shit out of my players. Whether it’s four-hour combat scenes where hit points are slowly ground away, shopping scenes where some players weigh up the merits of equipment while others drink all the beer in the house, conflicts that are rushed through so people can catch the last train home or just playing out situations that no-one gives a shit about, I’ve made every pacing mistake there is to make. And I’m glad, because I have passed through the fire and burned away my flaws (and possibly my eyebrows). There is a rhythm and flow to pacing, to compressing the dull-but-necessary bits and expanding out the thrilling bits while making sure they stay thrilling, and nothing teaches this to you like your small audience showing its displeasure or engagement by paying attention or falling asleep. And all of that translates directly to prose writing.

Scene framing

This is a vital pacing tool, but it’s also important enough to the narrative to warrant a special mention. ‘Scene framing’ is the simple act of setting a scene for play – deciding on the environment, situation and stakes and then determining the characters’ involvement. Depending on the game, it can be a naturalistic outcome of events – ‘you open the door and there are six demons playing poker’ – or a cut to a new situation ‘it’s two weeks after your wife left you and you come home to find the cat on fire’. Good, assertive scene framing is important because it a) sets up a scene for immediate conflict, b) trims away all the narrative fat from before the scene to focus on the core, which is good for pacing, and c) gives every character in the scene a hook or purpose for being there, which can come from the player or from the GM. Using these principles to set scenes makes for engaging play – and for engaging reading when you carry the same approach over to fiction.

Engaging conflicts

I know I keep saying this, but drama is all about conflict, and RPGs are great at conflict. Admittedly, most of them focus on one kind of conflict, which is the punching/shooting/swording etc kind. RPGs started life as a spin-off from wargames, and that legacy is why many games have a 60-page chapter of combat rules and four paragraphs on how to talk to people to get what you want. But all kinds of conflicts come up in games, and many games have systems or frameworks for exploring them in an enjoyable way. More importantly, RPGs are about pushing conflicts to find some kind of concrete outcome, from killing the troll to convincing the sheriff of your innocence, and it’s wanting to find what that outcome will be that keeps players engaged rather than seeing the whole thing as a speedbump – and the same goes for fiction readers. Some indie games go so far as to set explicit stakes before gaming through a conflict, which is something worth considering for your fiction – but then again, the naturalistic approach of ‘person left standing at the end decides what happens next’ can also make for strong writing. What really matters is that the conflict is meaningful to the characters and the outcome is in doubt; that’s what keeps people reading.

Exploring consequences

And what are the outcomes of the conflict? How do they shape the story that follows? Actions have consequences, and pretty much every RPG is based around following the track of those consequences. A linear dungeon crawl still works its way through a chain of consequences, be it ‘we beat the dragon, took its treasure and spent it on booze and a helm of alignment change‘ or ‘we all got killed by goblins and now the village is on fire’. A twisty, intricate urban horror fantasy might juggle a dozen subplots, but the overall progression of the game will still hinge on how the outcome of one plot has a knock-on effect on another and then feeds into a third, a fourth, a tenth. A dull conflict is one whose outcomes don’t go anyway, like a ‘trash mob’ fight in an MMO; a good conflict is one where the consequences shape play a dozen sessions later, even if only in a minor way. And it pretty much goes without saying that this same principle applies to fiction; that the seeds sown by the very first situation are reaped (along with many others) at the end of your book.

–

Huh. Usually I manage to include more (allegedly) humourous asides in these posts. Guess I have my serious pants on tonight.

There are other tools that can come across from gaming – world-building is a big part of game design, and a lot of that translates well to doing the same in prose – but these are the big ones for me. More pertinently, these are ones that come out in actual play, rather than the planning stages, and ones that get honed and refined the more actual game playing or GMing you do.

And because of that, these are tools and skills that you learn by doing – the best, the only way to pick up the strengths of gaming and bring them to prose writing is to get in there and play or run a game (and preferably a lot more than one). If you’ve not tried roleplaying but you’d like to give it a try and see what you learn, there are a number of fantastic games out there that can demonstrate all the things I’ve been talking about – check out Dungeon World, Fiasco, Smallville (yes, really), the various World of Darkness games, Don’t Rest Your Head, Fate Core or Fate Accelerated, Mutant City Blues or straight-up Dungeons & Dragons (4th edition is my favourite). All of these are great games that showcase some or all of the concepts I’ve been talking about.

And because of that, these are tools and skills that you learn by doing – the best, the only way to pick up the strengths of gaming and bring them to prose writing is to get in there and play or run a game (and preferably a lot more than one). If you’ve not tried roleplaying but you’d like to give it a try and see what you learn, there are a number of fantastic games out there that can demonstrate all the things I’ve been talking about – check out Dungeon World, Fiasco, Smallville (yes, really), the various World of Darkness games, Don’t Rest Your Head, Fate Core or Fate Accelerated, Mutant City Blues or straight-up Dungeons & Dragons (4th edition is my favourite). All of these are great games that showcase some or all of the concepts I’ve been talking about.

Hell, if you live in Melbourne and you want to give ‘em a try, leave a comment. I can always do with more players.

(And if you’re interested in reading more about my gaming adventures and ideas, check out my gaming Tumblr Save vs Facemelt and the ongoing story of my D&D campaign Exile Empire over at Obsidian Portal.)

June 2, 2013

We pause for radio station identification

It occurs to me that this blog has been going for about two years now, give or take a month, and that new readers may be stumbling over it every now and then due to links on Twitter or Googling ‘Batman and grammar pedantry’ or something similar. According to Google Analytics, 75% of the visitors to the site in the last month were new – and sure, while most of those were spambots, there may be a few new readers who came for the writing essays and stayed for the geekishness and swearing.

So for those new readers, here’s a bit of a breakdown of my various books, what they’re about and where you can get them.

(Meanwhile, maybe you established readers could link to this page on social media and tell everyone you know to buy my stuff. Come on, this trip to Paris isn’t going to pay for itself.)

–

The cleaning lady eats time. The manager mourns his multi-gendered parent. A pirate radio DJ listens for God. An accountant prepares to kill again. And that’s only in four rooms of the Hotel Flamingo, where the room service is terrible and reality flakes and crumbles around the edges.

The cleaning lady eats time. The manager mourns his multi-gendered parent. A pirate radio DJ listens for God. An accountant prepares to kill again. And that’s only in four rooms of the Hotel Flamingo, where the room service is terrible and reality flakes and crumbles around the edges.

Come to a part of town where the dealers meet, where the forgotten people hide, where reality cracks and peels like cheap wallpaper. Where normal is a dirty word. And while you’re here, come stay at the Hotel Flamingo – a refuge for resentful angels, feral symbols, disgraced magicians, broken-hearted foundlings, bad dreams and many others.

Hotel Flamingo is a weird fantasy/horror novella that I originally wrote as a serial on my LiveJournal back when people had LiveJournals. It’s what I call a ‘mosaic’ novella; each of its 22 vignette-chapters focuses on a single character at the Hotel, giving a snapshot of their unique and bizarre life and then tying that thread into the larger story until it all comes together at the end. It’s a story about fate and destiny, the power of symbols, good intentions and bad decisions. It’s got some of my favourite bits of writing in it, and a lot of people have told me they really loved it, which makes me very happy.

Hotel Flamingo is available as a 99-cent ebook from the usual places – Amazon, Smashwords, Barnes & Noble, the Kobo Store, the iBookstore and so on.

–

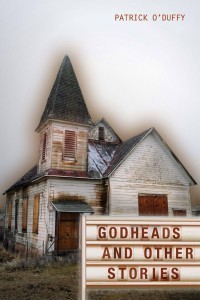

A man wakes up to find he’s turned into a Franz Kafka novel. A couple get high on illegal gods before going out dancing. An author tries to prove the existence of fictional ghosts by creating his own. A weary traveller realises that people keep disappearing from his late-night bus. A fledgling paranormal investigator is confronted by the ghost of a ghost. And two pensioners wait for the bus to take them to the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

A man wakes up to find he’s turned into a Franz Kafka novel. A couple get high on illegal gods before going out dancing. An author tries to prove the existence of fictional ghosts by creating his own. A weary traveller realises that people keep disappearing from his late-night bus. A fledgling paranormal investigator is confronted by the ghost of a ghost. And two pensioners wait for the bus to take them to the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

Godheads and Other Stories is an anthology of six weird fantasy and horror stories. They’re all stories, in their own way, about the intersection between high weirdness and low mundaneness, and how even the very strange can see normal once you get used to it.

There’s a pretty wide range of tones and voices in the stories in Godheads, which were written at different times in my life. The titular story is one of my earliest polished pieces, and clocks in at about 5000 words, while other stories are more recent and much shorter. Some stories are funny, some are sad, but they’re all meant to be unsettling to some degree or another. Who knows, maybe you’ll spontaneously turn into a piece of early 20th-century literature one day. Chilling, no?

Godheads and Other Stories is also available as a 99-cent ebook wherever you would normally buy ebooks - Amazon, Smashwords, Barnes & Noble, the Kobo Store, the iBookstore and so on.

–

This one is very straightforward – nine flash fiction stories for 99 cents.

This one is very straightforward – nine flash fiction stories for 99 cents.

What kind of stories? There’s some horror, some fantasy, some comedy, some more literary slice-of-life stuff. Topics include doll dismemberment, rock band murder, ghost moustaches, giant spiders, unicorns, cooking for ogres and Godzilla sex, and each story is less than 1000 words.

There’s not a lot more to say about a flash fiction collection, is there? I always compare flash fiction to Ramones songs – short, punchy, often rough around the edges and then BOOM DONE start the next one and then wrap up the set. And that’s as both a writer and a reader – flash stories are quick to cook, quick to digest, and if they leave you with a pleasant aftertaste then I think I’ve done my job.

So if you’re keen to read ‘Got the Horn’, ‘Ghost (Moustache) Story’, ‘Dear Penthouse Forum: I Fucked Godzilla’ and the other six stories in this collection, you can get it for less than a dollar from Amazon, Smashwords, Barnes & Noble, the Kobo Store and other places. It’s not on the iBookstore yet for some reason, though, and I wish I knew why.

–

Kendall Barber calls himself an obituarist – a social media undertaker who settles accounts for the dead. If you need your loved one’s Twitter account closed down or one last blog post to be made, he’ll take care of it, while also making sure that identity thieves can’t access forgotten personal data. It’s his way of making amends for his past, a path that has seen him return to the seedy city of Port Virtue after years in exile.

Kendall Barber calls himself an obituarist – a social media undertaker who settles accounts for the dead. If you need your loved one’s Twitter account closed down or one last blog post to be made, he’ll take care of it, while also making sure that identity thieves can’t access forgotten personal data. It’s his way of making amends for his past, a path that has seen him return to the seedy city of Port Virtue after years in exile.

But now Kendall’s past is reaching out to drag him back into the world of identity theft, just as he gets in over his head with a beautiful new client whose dead brother may have been murdered – if he’s even dead at all. Chased by bikers, slapped around by Samoans and hassled by the police, all Kendall wants to do is close the case and impress his client without winding up just as deceased as the usual subjects of his work. Will the obituarist have to write his own death notice? Or can Kendall turn the tables and put this body to rest?

The Obituarist is a crime novella about identity theft, the digital afterlife industry, death and redemption. It’s my attempt to write a Chandleresque detective story, except with more humour, and to examine the growing issue of what happens to the online portion of our lives when the offline portion comes to an end. I had a lot of fun writing it and a lot of people seem to have really enjoyed it, so I’m planning on writing a sequel later this year.

The Obituarist is available as a $2.99 ebook from (here we go again) Amazon, Smashwords, Barnes & Noble, the Kobo Store, the iBookstore and etc.

–

Free short fiction

Sure, 99 cents isn’t a lot of money, but you still don’t want to shell it out without some idea of whether I can actually write or not.

Sure, 99 cents isn’t a lot of money, but you still don’t want to shell it out without some idea of whether I can actually write or not.

That’s why I have six short stories available totally free to download from your preferred ebook seller! Well, unless your preferred seller is Amazon, as they don’t distribute free indie material. Poops. But you can get Kindle-compatible versions from Smashwords instead.

The stories I have up at the moment are:

‘The Descent’: When Mister Smith looks out the window of a plane and sees a man standing on a cloud, nothing else in life seems to matter as much anymore.

‘Watching the Fireworks’: A mirror breaks, a marriage explodes, and all the fine things they once collected and showed off now serve to demonstrate just what went wrong.

‘The Recent 86 Tram Disaster as Outlined in a Series of Ten Character Studies’: What caused the recent explosion on the 86 tram? Who were the people who witnessed the event? And how does the omniscient viewpoint of a narrator affect the lives of those characters it describes?

‘Hearts of Ice’: You come home one night, worn out by another day of hard work and not falling back into bad habits, to find the woman you love has left you. What now?

‘Pension Day’: Dunny thought that he was onto a good thing when he stole that cab and used it to rob old-age pensioners. But today he may have picked up the wrong passenger…

‘The Obituarist: Inbox Zero’: Kendall Barber has discovered something an email set up to be sent after a man’s death. What is in the email – and why is his client, the dead man’s brother, so eager to find out? This short story is a stand-alone mini-sequel to The Obituarist.

There’s some weirdness, some crime, some metatext and some just plain old storytelling there, all in a variety of formats. The easiest way to find them is from my author page on the various sites – Smashwords, Barnes & Noble, the Kobo Store and the iBookstore. The first four of those stories are also on the Downloads page here as free PDFs; the last two will go up there sometime soon once I get the time to format and upload them.

–

If you haven’t read any of these books or stories, then I hope you’ll go check some of them out. I think they’re worth your time.

Once you have read them, and assuming you like them (oh please god like them), it’d be great if you told other people about them on social media, gave them positive reviews on store sites, pressed them upon friends and relatives, sent me the spare change behind your couch cushions and generally did all the things that help independent writers let the world know that they exist.

It would also be cooler than cool if you liked my Facebook page, followed me on Twitter, rated my books on Goodreads and – more than anything else – left the occasional comment on this here blog to let me know that you liked my stuff and/or think that my latest blog entry is a pile of wank. Both are good, as long as you’re a human and not a spambot.

If you are a spambot, that’s okay. We can still be friends. Just not close friends.

Thanks for your patience, folks. Next week we’ll talk about something else!

May 30, 2013

Pods and paxes

Howdy gang,

Just a quick heads-up to let you know that I’m a guest on the Taleteller Podcast this week! My first ever podcast! An opportunity to listen to my voice and realise how often I say ‘um’ and stumble over my sentences!

Anyway, wince-inducing vocals aside, I had a good long chat to host Philippe Perez about writing, travel, discipline, short fiction and a bunch of other things. It was a lot of fun! I hope some of you will give it a listen and maybe even get something out of it.

–

Moving into the near future, here’s another heads-up for anyone going to PAX Australia in July – I’ll be on a panel talking about role-playing games! I’m on there with Chaosium writer/editor Mark Morrison and Paizo/Pathfinder writer Mark Goodall, and we’ll be talking about writing games, running games, developing ideas, working for publishers and anything people ask us about. The PAX schedule doesn’t seem to be set as yet, but I think our panel is on the Sunday afternoon. So if you’re there and want to hear us talking about the best way to really get into the head of a 13th-level Half-Dragon Anti-Paladin and sell him to an audience, drop on by.

–

Also, I have a cold.

That’s not so much news as just me whining, though.

May 26, 2013

Editors in the wild – a public service announcement

I’ve seen some confusion around the traps of late about the different roles covered by the tag ‘editor’, so I thought it’d be useful to give y’all a breakdown on what editors are and what they do in the book publishing business.

KNOW YOUR EDITOR. YOUR LIFE MAY DEPEND ON IT! You will not be able to see his eyes because of Tea-Shades, but his knuckles will be white from inner tension and his pants will be crusted with semen from constantly jacking off when he can’t find a rape victim. He will stagger and babble when questioned. He will not respect your badge. The Editor fears nothing. He will attack, for no reason, with every weapon at his command – including yours. BEWARE. Any officer apprehending a suspected editor should use all necessary force immediately. One stitch in time (on him) will usually save nine on you. Good luck.

Wait, that’s not right. Let me start again.

This is actually a tricky business, because different companies, industries and countries have different names for the same role, or the same name for different roles. But I’m just gonna roll with what I know.

Proofreader

This is a person who reads proofs, just like it says on the tin – ‘proofs’ being the laid-out pages from the typesetter that then get printed as the final book. A proofreader’s job is to go through proofs and mark up any typographical or layout errors they find so that the typesetter can correct them and then send the pages to print. And that’s it. They don’t make changes themselves, they don’t suggest improvements, they don’t alter the text in any way – it’s all about pointing out errors that someone else can then fix. This is why proofreaders provide the cheapest editing service, but also the one that’s least useful for most writers, because all you’re catching are basic errors and you still need to clean them up yourself.

Copy editor

This is what folks often muddle up with proofreaders – the people who get into a piece of writing and fix up any problems. Copy editors look for spelling, grammar and punctuation errors, as well as oddball formatting things like a paragraph being underlined for no reason, and they correct those things before the MS is typeset or laid out. Depending on the project, they might also apply styles and format text, but then again they might not. The key thing about copy editors is that they work on a sentence level, fixing up technical problems, but without looking at the text as a whole; they don’t care if the collective makes sense or is worth reading, just whether the individual bits work on their own.

Substantive/development/content/critical/I’ve-probably-missed-one editor

Or, as they’re often called, ‘editors’. This is the big umbrella of folks who look at the entire manuscript, tell you what’s wrong with it and (depending on the agreement) fix/change it as needed to make it the best book it can be. In non-fiction, development might mean bringing the MS in line with a specific structure, re-ordering material, updating details and (possibly) fact checking. In fiction, it can mean changing plots and characters, tightening language, requesting additional content from the author and more. Substantive editing is the Big Fun Exciting Editing, at least as far as I’m concerned, but it’s also the one that requires a strong relationship with the author, a shared vision and an assumption of trust. Otherwise you get your author copies when the book’s published to find your teenage protagonist has been replaced with Starscream.

Technical editor

Technical editors are kind of like substantive editors, but they’re attached more to the production/design/layout end of things than the writing end. Fact checking and content editing is probably a concern, but so is consistently styling of headings, layouts, images, fonts, page breaks and other structural features. If you’re writing or contributing to a highly designed book, like a technical manual or textbook, then a technical editor is probably going to make sure all your work fits that design; if you’re writing fiction, then there isn’t the same need.

Compiling editor

If you ever pick up an anthology and it says ‘edited by BLAH DE BLAH’, then that person is a compiling editor, a role that (perversely) doesn’t really involve any editing at all. A compiling editor who assembles material probably doesn’t actively edit any of it, and if they do it’s usually only the lightest of edits done in consultation with the author. What a consulting editor provides is a consistent vision for what the book/project is and what pieces of text should be in there, usually then going to individual authors and asking them to contribute. That’s no small job. And it gets your name on the book cover, which is pretty sweet.

Series/line editor

‘Vision’ is also the job of the series editor, a job mostly found in work-for-hire or media-based properties. Akin to the showrunner of a TV show, a line editor makes sure that the material submitted by authors fits the vision for the property, both right now and as part of future plans and developments. If it doesn’t, the editor may need to rewrite it themselves or push it out to another writing for revision. When the series editor has a light touch and gives writers room, you can get great, unique stories. When they’re hamfisted commanders of the IP who view writers as interchangeable word engines, you get New 52 DC comics OOH SICK BURN

They made Captain Carrot grim and gritty WHAT THE HELL PEOPLE

Permissions editor

If a book has copyrighted material in it that wasn’t created by the author – quotes, song lyrics, images – then the publisher needs to get permission from the rights holder to use it, usually paying for it. A novel might have only a couple of such items (or none at all), while a textbook could have like a thousand. Sourcing and negotiating for that material is the job of the permissions editor. It’s a job that involves working with image libraries and other publishers, tracking down rights holders, grappling with legislation and a bunch of other tasks. I wouldn’t do it for quids.

Project editor

If your contact in a publishing house is called a project editor, that means they’re working on 5-10 other books at the same time as yours. Project editors are in-house editors who juggle a set of books for the company, hiring freelancers to do the copy or content editing while they give what oversight they have time to provide, all the while working with the publishing and production department. It’s a big workload and one that requires a lot of organisational skills, while still demanding a fair bit of editorial input and direction. So be patient if they don’t answer your emails right away.

Commissioning/acquisitions editor

The last one really isn’t an editor at all, for the most part; this is another word for ‘publisher’, used mainly to distinguish between the person and the company as a whole. Commissioning editors are the ones who choose the books that get published, whether by going out and commissioning work to be written or deciding to acquire already-written texts for their house. They’re the ones who build relationships with writers, the ones you submit your work to, the first ones to read it and decide whether it’s good or not; everyone else listed above follows after them on the road to getting a book in print. This is what I do for a living, although rather than work with boring old fiction I work in the sexy, sexy world of commissioning high school maths textbooks hey wait come back I wasn’t done.

–

Got all that? Well, good, but don’t rely on it too much; different places break roles down in different ways. There’s a lot of crossover between these jobs, especially once you get inside a publishing company. A commissioning editor probably also acts as a substantive editor; a compiling editor might also handle permissions; the line editors I’ve worked with also did a bunch of copy editing on my first drafts. Pretty much the only thing consistent across the board is proofreading.

Let’s not even get started on how there are totally different roles and breakdowns of duties in periodical/newspaper/magazine editing, online editing or other specialist forms of print media. And film and TV editing is COMPLETELY DIFFERENT AGAIN. Fuck it, let’s all go get drunk.

The key thing to take away is this: saying ‘I need an editor’ isn’t enough. Not when looking for someone to work on your book, not when thinking about what needs to be done to your book, not when talking to whoever’s changing your work to fit their remit. If you’re self-publishing, work out exactly what kind of service you want before you hire someone, or you may end up paying a tonne of money for work you didn’t want or need. If your book is being handled by a publisher, work out who’s doing what to your work so you know who to talk to and how to supply the direction and feedback they need, rather than wasting time/effort with the wrong person or at the wrong stage of the process.

And if you end up working for me, please don’t submit your diagrams in longhand. Redoing that stuff digitally eats up my whole freaking week.

May 23, 2013

Got my hands full

Hey space cadets,

I’m kind of distracted right now because I’m working on my pitch/application for the Wheeler Centre’s Hot Desk Fellowship, a great program where the Centre gives writers a desk, a quiet space and a thousand bucks and asks only that they knuckle down and write in return. If that sounds cool, you should apply for consideration, as they have several slots free; just make sure to a) get it done by Monday and b) not push me out by being better than me. I WILL take that personally.

I’m also distracted by my aged mother, but the less said about that the better. It’s all a bit crazy up in here.

Anyhoo, in lieu of me entertaining you this evening, how about you go read the AMAZEBALLS responses to Text Publishing’s editorial want ad, download the new Splendid Chaps podcast and check out Subatomic Party Girls over at Comixology. That should keep you going until Sunday night.

May 20, 2013

The winner takes it all

Hey folks. Last weekend – using ‘weekend’ as a synonym for ‘Monday night’ because shut up – I talked about writing stories about failure, or that drove towards failure. You know, the sorts of stories that most people don’t want to read.

What do people prefer? Stories about success, unsurprisingly; stories about protagonists who overcome conflicts and succeed at their goals. Sometimes those protagonists are regular people; sometimes they’re Superman or Commander Shepard (FEMSHEP 4 LIFE). You know, stories that are fun rather than being a massive downer; stories that have a satisfying climactic ending rather than a gear-shifting anti-climax.

And yet, for all the fact that people (myself included) love these sorts of stories, they’re very easy to do badly. I’ve read too many stories and seen waaaaay too many movies where success seems pedestrian rather than exciting, where heroic competence is dull rather than engaging, and where the climax feels safe and predictable rather than exhilarating.

And yet, for all the fact that people (myself included) love these sorts of stories, they’re very easy to do badly. I’ve read too many stories and seen waaaaay too many movies where success seems pedestrian rather than exciting, where heroic competence is dull rather than engaging, and where the climax feels safe and predictable rather than exhilarating.

So once again Mister Tells-You-How-to-Write-Despite-Never-Finishing-Anything is here to give you some tips, this time on writing a strong story about a successful, engaging character. Trust me, I’ve read a lot of Batman comics, I’ve played a lot of D&D; I know how this shit works.

Success comes from competence

You have a main character and she’s awesome. She has two guns and she can pick any lock. And when she gets to the secret base to steal the gold-plated McGuffin, she walks in and out unmolested because Count Bad Guy trips over a staircase and knocks himself out rather than fighting her. Is that an exciting story?

The key to drama is conflict, and the key to an engaging, meaningful conflict is that victory has to be earned rather than given away. It’s important that the character succeeds through their own skill, ability and effort, not just through lucky breaks or through their opposition stuffing up. A hero who wins the day thanks to their rival’s incompetence or because she walked through the right door isn’t interesting, and their conflict (and victory) feels false. So when bringing your character out on stage, show off her skills – don’t hide her light under a bushel. Let her be aware of what she’s good at, let her use those abilities and let them be effective in overcoming obstacles and conflicts.

Failure comes from someone else’s competence

You want your character to win at the end, yes, but along the way it’s good for them to have a few setbacks and take a couple of knocks, if only so that they can bounce back from the defeat and learn from it. But if those setbacks are due to them not being skilled or strong enough to have a chance in conflicts (your hero has two guns but doesn’t know how to shoot them), or if she fails due to bad luck or random chance (her lockpicks get stolen by pigeons along with her lunch), then she doesn’t come across as a credible hero, she comes across as a schmuck.

The way to frame defeats, then, is to give your character competent opposition, antagonists or dangers that are simply greater than even her skills can overcome. She’s a crack shot with her pistols, but Count Bad Guy has bulletproof handwavium skin; she can read minds, but that doesn’t help when her yacht hits an iceberg. Situations like this position your antagonists and dangers as being meaningful and relevant, rather than just set dressing or minor speedbumps, because we never know if or how the hero will prevail. But prevail she will, because these conflicts can’t stop the narrative short; instead, the character can find new ways to get around the obstacle, either through improving skills (making armour-piercing handwavium bullets) or applying different abilities (picking the lock of the frigid prison at the heart of the iceberg).

Randomness brings narrative opportunities

So if you can’t use bad luck or external events to make your character win or lose, then what are they good for? Glad you asked. These externalities - sudden rainstorms, food poisoning, everyone in Chicago turning in a werewolf – open up new avenues for conflicts. A gunfight on the top of a burning skyscraper, with no way of getting off, is a lot more engaging than a gunfight in an empty street on a sunny day. Your hero can pick any lock with the right tools, but her picks were stolen by pigeons (remember?); now she had to improvise tools from bits of frozen scraps before the ice prison sinks. The context of the conflict changes, the parameters of description change, and everything gets more interesting.

External factors like this are also a good way of opening up new directions for the story, because they allow for different consequences and to explore the reactions of the main characters to those consequences. Your hero didn’t set that skyscraper on fire herself, and in fact got burned in the blaze, but now everyone blames her and she must avoid the police while seeking medical treatment. She escaped from the frozen prison before it sank, but now she’s stranded in the Arctic and the ice wolves are coming. None of these things are her fault, but they keep the dangers and conflicts flowing even after she’s succeeded to doing what she needed to do – she reacts to them, rather than them being reactions to her.

Flaws and weaknesses increase the awesome

It goes without saying that flawed characters are more interesting than perfect ones. (And in case it doesn’t, I’ll state it quickly - flawed characters are more interesting than perfect ones.) But flaws need to have an impact on the story to feel meaningful; your character being frightened of octopi doesn’t matter if the entire story takes place in the desert. A good way to make those flaws meaningful is for them to open up new conflicts as the character reacts against them – like an external problem, but internalised. Your hero hates Nazis, so she goes out of her way to bust up a ring of Illinois Nazi werewolves, and now she has to take them on at the same time as fighting Count Bad Guy. If she could have left well enough alone… the story would have been duller.

The other good way of making weaknesses work is to use them to raise the stakes in conflicts. Your hero has a bad temper, so when a contract negotiation goes bad she kicks over a table and calls the Pope a motherfucker. Now this negotiation is a lot more complex and difficult, and if she can’t mollify the Pope he’s gonna open up a can of white smoke on her arse – and won’t lend her the Vatican Guard to help her fight the Illinois Nazi werewolves. Which is going to really hurt when the ice wolves come for her in the Arctic… Flaws exist to get your character into trouble; trouble exists to make conflicts feel more important.

The other good way of making weaknesses work is to use them to raise the stakes in conflicts. Your hero has a bad temper, so when a contract negotiation goes bad she kicks over a table and calls the Pope a motherfucker. Now this negotiation is a lot more complex and difficult, and if she can’t mollify the Pope he’s gonna open up a can of white smoke on her arse – and won’t lend her the Vatican Guard to help her fight the Illinois Nazi werewolves. Which is going to really hurt when the ice wolves come for her in the Arctic… Flaws exist to get your character into trouble; trouble exists to make conflicts feel more important.

Victory has a price

Nothing in this world comes for free; victory needs not just hard work but sacrifice. For success to feel important, it kind of has to suck for the hero; she needs to give up something in the process. It might be love, happiness, her left arm, the chance to live a normal life or even her life, but whatever it is, it has to hurt; it has to be a price she would rather not pay. This is where too many blockbuster films slip up – the hero works for a victory (often by punching/shooting lots of people) but never sacrifices anything, never has to lose anything important to her to save what’s important for others. There’s no note of sadness (or at best a temporary one) in the relentless bugling of success.

And this, in turn, is the flip side of last week’s discussion. In a story of failure, the protagonist gives up the big goal for the small goal; they choose to fail at one in order to succeed at the other. It’s exactly the same in a story of success, but the priority remains as it was at the start of the story; the main goal is achieved, but the secondary, personal goal is forever lost. Batman can never be happy; Ripley never gets to build a life with Hicks and Newt; Commander Kirk can never just spend his days banging hot aliens. (Well, not unless the film is dumb.) Maybe it comes down to a choice, maybe it doesn’t; maybe the price is paid early, maybe right at the end. But winning has to be a kind of loss; that’s how you know it was worth it.

–

I really should workshop this gun-toting Nazi-werewolf-fighting cat-burglar concept more. There’s at least a novella in it.

–

Come back next week when I talk about editing! Or something else if I change my mind!

May 13, 2013

Fail to win, win to fail

No one in the world ever gets what they want and that is beautiful

Everybody dies frustrated and sad and that is beautiful

No, I’m not depressed (I’m pretty much never depressed), nor am I quoting They Might Be Giants lyrics just because I saw them live earlier this month (an excellent gig). It’s just that I’ve been thinking about failure, as I am often wont to do, particularly on those days when I blow my own self-imposed schedule of writing blog posts on Sunday nights.

I like stories about failure; I like books where the main character sets out to do one thing at the start and ends up doing something fundamentally incompatible with that at the end. You know, books like Michael Chabon writes; pretty much all his novels are about failure on some level, especially Wonder Boys and Telegraph Avenue, both of which I loved. (His other main theme is dysfunctional father-son relationships, so it’s really like he’s writing books just for me.)

I like stories about failure; I like books where the main character sets out to do one thing at the start and ends up doing something fundamentally incompatible with that at the end. You know, books like Michael Chabon writes; pretty much all his novels are about failure on some level, especially Wonder Boys and Telegraph Avenue, both of which I loved. (His other main theme is dysfunctional father-son relationships, so it’s really like he’s writing books just for me.)

Stories about failure aren’t that popular, which is hardly surprising; we tend to prefer stories about success and overcoming odds, which are cathartic and dramatically satisfying. Last night we saw Star Trek: Into Darkness, for instance, which was well-produced and thrilling enough (albeit a bit ordinary on the whole), but there’s nothing in that movie about failure, and nor should there be. That wouldn’t be much fun. Still, sometimes you don’t want fun; sometimes you want to taste that human sadness, and a story about failure has that salty flavour.

So if you want to write stories that melt like mediocrity on the tongue (yep, taken the metaphor too far again), here are a few pointers on how to mix the recipe (doing it again PULL OUT PULL OUT):

Tell the right story at the right length

Genre stories of almost any stripe are rarely appropriate for fail-stories. You could say it’s because genre stories are about plot and fail-stories are about character, but that’s too reductive. Better to say that genre is about exploring ideas and seeing them through to fruition; fail-stories are is about swerving away from that fruition. We want to see the Dark Lord defeated, the mystery solved, the hot plumber nailed harder than Jesus; dash that expectation and there’s not much point in continuing. So fail-stories are generally the traffic of lit-fic; you can pull off something downbeat and melancholy and frustrated in genre, sure, but if you’re not Ursula le Guin maybe it’s best to try something else.

The other thing about fail-stories is that they tend to be either short or long, not medium-sized. Short stories are good fodder for fail-stories, because you can get in, set parameters, subvert them and then get out before anyone has a chance to get disappointed, like jazz in a minor key. Longer stories give you more opportunity to build connection and empathy for your main character (see below), which makes the process of failing more viscerally satisfying. Going for something in between, like a novella or a serial fiction, is trickier.

Focus on building empathy

Like I said, it’s not about prioritising character over plot, except that I lied and it totally is.

If we don’t care about a character, their failures are just boring; if we do care about them, their failures consume us. If we can put ourselves in their shoes and want what they want, need what they need, then their inability to gain those things hurts us, reminds us of all the times we fell short ourselves. To hit that point, we need more than just interest in or enjoyment of a character; lots of people like James Bond but a film where he failed to save the world would not make us happy.

What we need is to identify with the character, rather than idolise them. They need to be someone at our own level, be that conceptually or emotionally or what-have-you; they need to be someone sharing our skin. We need to understand their choices and their pain; we need to be able to nod knowingly and think yes, I’d have done the same thing, damnit. Without that sympathy, we don’t care that Jane Doe didn’t find true love among the dugong-people of Neptune and instead became a Venusian hermit, we just feel frustrated that all that hot manatee-love didn’t materialise and oh God this example has gone very wrong.

Small victories, meaningful failures

The small victories / The cankers and medallions whoops sorry sudden Faith No More lyric let’s start again.

Look, no-one wants to read a book where the protagonist just gets his face rubbed in dogshit for 200 pages and then it’s the end. (If you do, please stop reading my blog, you’re creepy.) An engaging narrative has a constant escalation of challenge-response-challenge, a rising tension throughout the story’s arc – and to keep that arc rising in a fail-story, your protagonist still has to meet and overcome some of those challenges, just like in a regular and-then-he-saved-the-world-from-the-Star-Groaties novel. And no, you can’t just have him win at everything and then fuck up at the final hurdle, because that would just be shithouse.

Instead, your protagonist needs to win at the things that don’t matter to him and fail at the things that do, and what that means will vary from story to story. If the hero has to solve a crime while also keeping his marriage intact, you need to decide which of those is what matters to you, and thus which is what will matter to the character (and the reader). That usually means the one that’s most emotionally meaningful; a story where the detective gets closer to the killer while his marriage falls apart is more interesting that one where he can’t make sense of any clues but his husband can’t wait to go on dirty weekends with him. Go back to empathy; we understand those personal, human failures more than the fictional ones, so that’s where the focus needs to go.

Set stakes and then reset them

At the start of a story’s arc you define the conflicts and the stakes; this is what’s going down, this is the opposition, this is what will happen if the hero can’t get her shit together – and, most importantly, this is what the hero will have to sacrifice to reach her goals. This isn’t new; this is Storytelling 102, after the course in hey-maybe-your character-should-have-limbs. (Unless it’s important for the story that he doesn’t have limbs, which is cool too.)

The key manoeuvre in a fail-story is revisiting those conflicts and stakes around or just past the halfway mark of the arc and giving the character the opportunity to question them – to say ‘shit, maybe I’m not prepared to give up the thing that matters to me to obtain my goal’. I don’t mean that abstractly; I mean that the character has to confront that dilemma within the narrative, to question everything they’ve done before that point. And that’s the point where you posit new goals, conflicts and stakes; that’s the point where you lay out signposts to an alternative ending, one that both the readers and the characters can see.

Failure is a choice

And once those signposts are in place, you put it on your protagonist to decide while the reader is screaming in his ear no no turn back not that way! Because failure due to incompetence or intellectuality isn’t fun to read about, it’s just frustrating; it’s like a gaming session where the player rolls a 1 in the final session and bang there’s two years of the campaign fucked. Failure matters when it’s deliberate, when the hero throws in the towel, turns her back on the fight; when she decides that the TKO isn’t as important as going back to art school, or whatever.

Because in the end, an effective story about failure is a trick - it’s about success after all. It’s just that what ‘success’ means by the end of the story isn’t what it meant at the start. For example, Wonder Boys starts with Grady Tripp defining success as finishing his novel; by the end he defines it as being a decent husband and father, even if that means giving up on his life’s work. He fails at his first target, but that’s okay, because it stopped mattering to him as much as the second one – and because Chabon built empathy and immersed us in Tripp’s head and heart, that’s what matters to us too. Through an act of narrative aikido, the direction of the story’s desire is turned upon itself, and the character makes the choice to be flipped onto the mat.

Because in the end, an effective story about failure is a trick - it’s about success after all. It’s just that what ‘success’ means by the end of the story isn’t what it meant at the start. For example, Wonder Boys starts with Grady Tripp defining success as finishing his novel; by the end he defines it as being a decent husband and father, even if that means giving up on his life’s work. He fails at his first target, but that’s okay, because it stopped mattering to him as much as the second one – and because Chabon built empathy and immersed us in Tripp’s head and heart, that’s what matters to us too. Through an act of narrative aikido, the direction of the story’s desire is turned upon itself, and the character makes the choice to be flipped onto the mat.

It’s not failure. It’s just realising that you prefer the taste of defeat. And the reader, hopefully, will too.

–

I hope all that made sense. It’s been a long day. If not, I admit defeat OH SHIT YO SEE WHAT I DID THERE ah never mind.

As a counterpoint, next weekend I’ll talk about narratives of awesome success and how to make them not suck.

Because if anyone knows about awesome success, it’s me.

May 9, 2013

Don’t read this post

Just keep walking.

Don’t stop here.

This is bat country.

…come on, you know I never write anything worthwhile on a Thursday night.

Instead, go read one (or more) of these awesome things.

Author Peter Ball is liveblogging the progress of his new urban fantasy novella Claw (sequel to Horn and Blood) and it’s a fascinating look at the writing process. Peter has a dedication to the work that I can only envy and fear, taking whatever tiny sliver of time he can find in a day to sit down and pound out wordcount. This is great reading for anyone interested in writing; it’s also worth noting that Peter is a) a bloody good writer, b) one of the organisers of GenreCon, and c) excellent people, so keep reading everything he does.

You could be forgiven for thinking the federal election was next week, rather than four months away, as both major parties are in fullblown election mode. It’s tempting to just retreat into fiction for the duration and then just draw draw a dick and balls on the ballot paper come September 14. But I’m a big believer in informed, tactical voting, which is why I follow The Tally Room, Ben Raue’s breakdown of every federal electorate and analysis of its voting patterns. It’s never too early to work out how your neighbours swing, after all.

The Emerging Writers Festival starts in just two weeks! I’m not involved as a panelist or contributor this year, but don’t let that put you off. The EWF remains the most exciting, most inspiring and most educational writing event in Melbourne, and if writing is your passion (but not necessarily your main source of income) you absolutely need to go along to some events. I know I will, even if it’s just the ones held at pubs.

The Emerging Writers Festival starts in just two weeks! I’m not involved as a panelist or contributor this year, but don’t let that put you off. The EWF remains the most exciting, most inspiring and most educational writing event in Melbourne, and if writing is your passion (but not necessarily your main source of income) you absolutely need to go along to some events. I know I will, even if it’s just the ones held at pubs.I rabbit on about writing schedules and dedication and blah blah blah all the time, but my friend Dan directed me to this great blog that presents powerful tools for building routines in like a third of the space I would take. Go check it out.

I gave up on the forthcoming 5th/Next edition of D&D very early on, because it looks like balls and because 4th edition is my flavour, but I’m glad people are sticking with the ongoing playtest/pre-marketing and poking at it. One of the most interesting lines of criticism is coming from Tracy Hurley, aka Sarah Darkmagic, who tempers optimism over 5th‘s system with concerns about the game’s handling thus far of gender issues and presentations. There’s some smart, insightful talk over at her blog that’s well worth a look. Sadly you can’t leave comments, because Sarah is a woman talking about gaming and as such the comments section gets regularly trolled and poisoned AND THIS IS WHY WE CAN’T HAVE NICE THINGS.

Everyone knows about Kickstarter now, and we’re all tired of seeing campaigns that are totally bullshit, but this one’s the real deal – legendary comics creators Greg Rucka and Rick Burchett with a plan for a deluxe hardcover of their steampunk airship western fantasy comic Lady Sabre and the Pirates of the Ineffable Aether. If that’s the kind of genre celebration that appeals to you, get in there and pledge; they smashed their carefully-considered target in a matter of hours and are now into stretch goals. And if you’re not sure whether the comic’s good (it is), then go read it – the whole series is free online.

Everyone knows about Kickstarter now, and we’re all tired of seeing campaigns that are totally bullshit, but this one’s the real deal – legendary comics creators Greg Rucka and Rick Burchett with a plan for a deluxe hardcover of their steampunk airship western fantasy comic Lady Sabre and the Pirates of the Ineffable Aether. If that’s the kind of genre celebration that appeals to you, get in there and pledge; they smashed their carefully-considered target in a matter of hours and are now into stretch goals. And if you’re not sure whether the comic’s good (it is), then go read it – the whole series is free online.And speaking of e-comics, albeit not free ones, ex-Comics Alliance writer Chris Sims is writing a new series for Monkeybrain called Subatomic Party Girls, which appears to be ‘Josie and the Pussycats versus space pirates’ – and you’ve either recoiled in horror or immediately pulled out your wallet at that high concept. More details, and more of Chris’s varied writing, at the Invincible Super-Blog, a must-read for anyone who likes Batman, video games, sarcasm or reviews of superhero-themed pornography. Which is probably all of you.

One of my favourite bloggers (and best friends) is pregnant. And blogging about it. AND IT IS FUCKING HILARIOUS.

God bless the internet, that provides us with so much wonderful stuff.