Patrick O'Duffy's Blog, page 14

September 23, 2013

A month of maps – Exile Empire

Sorry for being a day late, folks – I spent yesterday playing D&D with my crew.

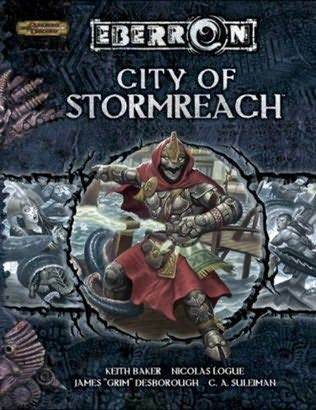

And hey, speaking of that, let’s make an incredible obvious segue into tonight’s post! Because rather than rough up another map for a story I’m writing / was writing / should be writing, I’d like to talk about the map I used for my D&D game – an urban Eberron campaign called Exile Empire. It’s been pottering along erratically for more than two years, and the city map I use has been the single biggest influence on the shape of the game. And I think the way I’ve used that map can inform not just gaming but storytelling in all forms.

So put aside your novels, slip on your d20-emblazoned boxer shorts and come check out this here map of Stormreach:

A few thoughts:

Oh, so pretty

Now that’s a proper map. It has streets and borders and funny-shaped buildings and everything. Who could help but get inspired by something like this, or this map of Freeport (partially shaped by yours truly) or any number of the gorgeous maps of Middle-Earth out there in the wilds?

There’s certainly value in an attractive map to the reader, but what value is there for the writer? How is this better than my godawful Word scribblings? Well, for one thing it’s actually interesting to look at, and anything that keeps you engaged in your work and your world is a good thing. Another strength is that it’s got genuine detail – you can see a lot more about the flow of movement and the change in local geography from this image, and that makes it easier to reflect in prose. And third, a good map does some of the work of evoking the setting for you. You’d have to read City of Stormreach to realise most of those buildings are overturned boats or hollowed-out giant stone heads, but this map still helps you communicate colour and shape, helps get across the feel of life in a seaside town that occasionally gets menaced by flying jellyfish from a dimension of madness.

Yes, that was a major campaign plotline. It was great.

Come selector

Come selector

The joy of a map with all the bits filled in – whether you did all the world building or you bought the city off the shelf – is seeing all the different places and locations spelled out for you, waiting to be used. You have the opportunity to select a story, rather than create one – or, if that’s too strong a statement, to create one using the building blocks that have already been assembled. Your world is rich in stories and potential stories; you can tease out and develop any one that you wish, leaving the rest for another time.

Is that a good way to write stories, though? Opinions will vary. I find it a difficult concept to consider – I want to write the story that explores my world and ideas, rather than just one of a variety of stories. Other writers will disagree, and want to benefit from the richness of a world that can bear multiple narratives. It’s certainly a powerful approach for writing short stories, especially if you’re sharing the sandbox with other writers – as in the old Thieves’ World series, which I also have some experience with. And it’s great for gaming, of course – which often is a lot like writing in a shared world anthology, with some co-writers at the table and others at the other end of whatever sourcebook you’re using.

The tyranny of the interesting bits

The thing about having all those engaging story elements pre-defined for you is that it can blind you to the power (or occasionally the necessity) of creating new elements in the moment. This is something I stumble into a lot in gaming – with so many toys to play with, why go to the trouble of making my own? Well, because those toys might have more direct relevance to the players, or their characters, or the themes I want to explore. And so it was with Stormreach. We had a lot of fun running around the Harbour District getting into fights, or setting fires to various taverns (okay, being in various taverns when they were set on fire), but it was when we went off the map to break a siege in the jungles that the campaign took a turn and several characters went through meaningful changes.

If you’ve put the work into creating a map, or a setting, or a court full of intrigues all before you start writing, that’s great – but don’t feel limited by the things you’ve already done. There’s always room to add a new location, introduce a new character, complicate or eliminate or double down on an existing relationship – and the stuff you make in the moment is at least as interesting to your readers/players as the stuff that was there all along. Maybe even more so.

Movement is story

When the Order of the Emerald Claw attacked Master Aedan in the Temple District, his student Slaine was in Cross, and it wasn’t until she’d come through the Marketplace that she came home to find him bleeding out. When the Storm Hammers opened a dimensional portal in the undercity, the heroes had to track down an entrance in the old Rubble Warren in Greystone. And when a giant fell taint bled lumps of diseased telepathy into the river, the adventurers had to race through a city beset by sickness and madness to hire a skiff, sail upriver and fight the horrible squishy thing.

A defined map has both locations and information about where those locations are in relationship to each other. The best stories are never set entirely within one place – they always involve movement from A to B, and that movement goes through C. The joy of a defined map is the chance to explore the transition between locations as well as the locations themselves – because that movement lets you see the world around the characters and locations, the effects events have on those interstitial spaces, and how they’re changed by the actions of the characters. It’s in that travel from one place to another that story happens and stakes raise for when you reach your destination.

Spin it round

Spin it round

What’s the northernmost location shown on this map? The district of Whitewash at the top? Nope – it’s the Foundry, location number 1 off to the right. That’s because the compass rose down in the bottom corner has north off to the right, while up the page is west.

For whatever cultural or neurological reasons, we always assume the top bit of the map is north, and it’s a disorienting wrench to re-align north to the left or right, and nearly impossible to spin it 180 to the bottom. If you want to disorient your readers, turn your map 90 degrees before it hits the page so that they’re always uncertain about how to translate the words ‘and then they walked six blocks north’ into something visual. However, if you prefer not to give your readers conceptual vertigo, skip the silly buggers and just make north the bit that goes up. It’s easier.

–

Hope y’all found that excursion into a different kind of map (and purpose for a map) interesting.

‘cos we’re doing it again in a few days, except completely differently.

Comments welcome, as always.

September 16, 2013

Month of maps – The Obituarist

Having put up my cruddy Word-drawn map of Crosswater last week to deafening acclaim – I must be deaf as I didn’t hear anything – I’d like to follow up with my map of Port Virtue, the seedy seaside city that is the setting of The Obituarist. It’s equally cruddy, but I think it shows how different stories have very different priorities, and how place can work very differently.

And now, through the magic of , I give you:

What the hell kind of map is this? I mean, last week’s attempt was a bit rubbish, but it least it had some proper features like rivers. This is just some words and an arrow pointing north – might as well be a mind map!

Well, yes – and it nearly was a mind map, but that started getting messy.

Tone first, geography second

When I looked back through The Obituarist to make this map – because I’d never drawn or envisioned one while writing it – I discovered that there was only one statement about a physical direction in the entire book. (Someone says ‘west side’ towards the end of the novella.) And yet Port Virtue is clear in my head – a run-down faded city of harsh lights, broken concrete and crappy nightlife – and readers have said to me that it’s been vivid for them as well. But all of that comes out through tone and from individual scenes, rather than how those scenes and places sit alongside each other.

Not every story needs a map, and not every map needs to show physical things. This diagram shows me tone more than anything else – there’s the boring part of town, a shitty part, a wet part where people probably get drowned, a relatively nice parts my stories will probably never visit and so on. Even though I have a rough direction marker, thanks to that one bit of dialogue, the important thing is seeing that if Kendall goes back to the crappy part (and he will) then it gets even crappy further out; if he stays at home he’ll get bored; if he goes into the middle of town there are cops on his arse again. That’s what I need and that’s what I think my readers want, more than a sense that Kendall can see the Brick House from his balcony.

As I said, I made this map after the fact (specifically I made it last night), and most of that work was trying to work out where various locations fit into my… let’s call it a ‘tonal gradient’ because it makes me sound clever. That’s an interesting experience – like trying to puzzle out directions that I’d forgotten I’d written, possibly due to drunkenness at some point.

It’s like – okay, D-Block’s hideout is on the waterfront, that’s obvious. But the Brick House is in the shitty industrial part of town, and that turned out to be on the other side of the city. The biker lab must also be over there, because it’s crappy as fuck – but it’s in an old housing district, so it’s probably near a residential area, and probably the boring part rather than the nicer part. Where should I put the storage place? Waterfront sounds good.

It’s part detective work, part jigsaw puzzle, part throwing shit to see where it sticks – and it’s kind of fun. If your story is done and you never created a map for it, there can be value in going back to it and working out where everything goes, whether physically or conceptually. It can help you see connections that hadn’t occurred to you, suggest ideas for further events and even encourage dreams where the old Clint Eastwood biker guy has brunch with Benny Boorns.

Um. Yeah.

No districts, no place names, no fiddle-dee-dee

The Obituarist is around 22 000 words long. I ain’t got time to be naming things! I can’t indulge my little fetish for portmanteaus; place names chew up wordcount every time they appear. Ditto descriptions of places as discrete units, or attempts to flesh out the context of the snippets of space I have for setting scenes. No, no time for that; just tone and purpose, that’s all there’s room for.

You write to fill the space you have; you edit down to fill the space you need. And if something isn’t actually useful in the story – a description, a place name, a WELCOME TO SHITSVILLE ACRES PLEASE COME AGAIN street sign – then cut that crap out. Or don’t write it in the first place.

A shame. Shitsville Acres is really quite lovely in the spring.

Room to expand

Like most modern cities, I figure Port Virtue doesn’t have a wall around it or a distinct start and finish. One moment you’re driving down a rutted highway, then you pass some crappy houses and burned-out trucks, and a couple of minutes later you’re being carjacked in a traffic jam and wishing you’d gone to Zurich for your holiday. Cities are smears on the landscape, and a lack of a formal boundary helps give that sense of reality to your place.

It also gives room to add more detail as ideas and stories demand. The cliffs and the Jericho estate come from the semi-sequel short story ‘Inbox Zero’ - completely free to download, if you haven’t already – and I figure that the Jericho Bible printing factory is somewhere along the waterfront. And out further west, we see a few hints of what’s coming in The Obituarist II: Electric Boogaloo, which I’ll be working one as soon as I finish with Raven’s Blood. Who is Old Man Northanger and why does he have a zoo and a scrap yard out in the boondocks? You’ll find out soon enough – and learn the terrible secret of what lurks in the boring part of town!

Well, maybe. Still working that part out. And it’s probably not that terrible a secret. Not unless the next story involves Scooby Doo.

…I’m not ruling that out.

–

Two different cities, two different maps, two (or more) different purposes for those maps. I think that’s kind of cool.

I hope some of y’all agree. Speak up if you do. Or don’t.

September 12, 2013

Time after (map) time

Just a quick mid-weeker tonight, folks, but I want to throw this out there.

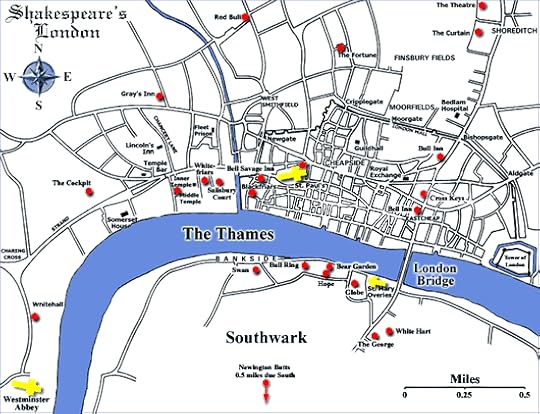

I’m basing a lot of Raven’s Blood’s aesthetics on Elizabethan England, albeit changed in a lot of major and minor ways. The native Westrons may have dark, almost Hispanic complexions, and the clothing may be sensible rather than risible – I’ve been reading about Elizabethan fashion and it was balls-out cray-cray – but still, Crosswater is meant to resemble Tudor London in a bunch of ways that (hopefully) make the story interesting and the setting evocative.

But here’s the thing – Elizabethan London was fucking tiny.

Here’s a rough map of what was considered London (i.e. the important bit that was then surrounded by farms and suburbs n’ crap) in Shakespeare’s day:

According to that scale that’s like, what, two miles across? Two and a half? And maybe one-and-a-half miles high. Westminster Abbey on one side, the Tower of London on the other, the Thames up the middle – that’s your city.

Now here’s a modern tourist’s map of London:

Twice the height, twice the breadth, four times the area, but we can still see where Shakespeare’s London fit in that lower right quadrant, still make out the same landmarks. They haven’t moved; it’s just that what we consider ‘the city’ has expanded hugely in the last few centuries.

So what’s the point? Well, a couple spring to mind:

- Shakespeare’s London was no more than maybe 3-4 square miles of land, but in there was crammed enough trade, intrigue, culture, religious tension and frenzied shagging to propel more than four hundred years of storytelling. There’s always an urge to give stories breathing room, to send your history back a thousand years rather than twenty or throw the dice out over a continent rather than a countryside, but you don’t need a million hectares or years to anchor a story; what you need is a concentration of people, of culture, of conflict. And you can find those in a backyard if you look hard enough.

- Cities expand over the ages, by and large, but history doesn’t flow as fast as real estate figures. There are stories about Kensington Gardens and Regent’s Park and Belgravia, but do they have the same resonance, the same hook for readers as stories about London Bridge and the Tower of London? Well, maybe they do for the folks who live around there, I don’t know; local stories matter to local people and so they should. But your readers are always tourists, never residents, and you’ll have a better chance of drawing them into your story if time and space are co-conspirators; if your fascinating place has a fascinating history to go with it, even if it’s a history that never gets spelled out.

- Speaking as an Australian, what the fuck London is tiny you could drop that shit in Brisbane and never find it again. Getting my head around the sheer freaking density of Britain, or indeed Europe in general, or indeed anywhere that isn’t an unpopulated urban wasteland punctuated by the occasional bottle shop and hipster mandolin collective just makes my head swim. I’m going to Europe at the end of the year, and I fully expect to freak the fuck out due to the sheer density of history and armpits.

Maps, people. They only tell part of the story. But it’s a crazy goddamn part.

September 8, 2013

Month of maps – Raven’s Blood

What I wanted to do today was mostly drink bourbon in bed with the covers over my head and maybe keep doing that for the next three years.

But no, we must soldier on; there are new battles to fight and more work to be done. And I don’t have any bourbon in the house anyway.

Instead, let’s talk about maps some more.

I promised I’d spend the month creating and then discussing maps for some of the projects I’ve been working on. So here, in all its glory, is my map of Crosswater, the city that is the setting of Raven’s Blood:

This is obviously a bit bare-bones, but it shows the core information about Crosswater’s geography – that it’s a town built around two rivers (the Dawn and the Dusk) that come together to let out into a harbour.

So what discussion points does this suggest?

Pretty and Useful Ain’t the Same Thing

If you’re looking at this map and thinking it looks like something I slapped together in MS Word in like twenty minutes, well, you’re perceptive. There’s no way this is going into the front pages of the book once it is snapped by Random Penguin and they print it to universal acclaim, or even if I end up publishing it myself and paying someone fifty bucks to do the map in Dundjinni or something.

But so what? This is a working document, not a finished product. Maps are tools, first and foremost, and this map does the job of presenting the relationship between places that I need it to do. If anything this is still more developed than it needs to be (note the sumptuous use of colour, after all); I could get just as much use out of a diagram, a mind map or some scribble in a notebook.

But so what? This is a working document, not a finished product. Maps are tools, first and foremost, and this map does the job of presenting the relationship between places that I need it to do. If anything this is still more developed than it needs to be (note the sumptuous use of colour, after all); I could get just as much use out of a diagram, a mind map or some scribble in a notebook.

If you’re sitting down to create a map for your project, don’t feel paralysed by any feeling that it requires visual polish. That comes at the end, when other people look at your stuff. When you make stuff to use, just do what works for you – anything more will distract you and is likely to need revising once you’re finished anyway.

Filling in Details as We Go

What are the names of the three untitled districts? Don’t know. What are the areas around the city? Don’t know. Are there additional districts and locations? How many ships are anchored at Dockside? Is there a wall to the north of the Commons? Don’t know, don’t know, don’t know (but probably). Bottom-up design is all about doing what’s required and no more, and this map shows everything that the narrative has demanded so far. Once I finish the book I’ll come in and fill in some of these blanks, because I’ll want to present a finished map, but there’s no need for that right now.

This map is also not to scale, because scale is also not something I really need yet. I know it takes about an hour to walk at night from the Arrowsmith manor to Kember’s house, because Kember does that, and that gives me some idea of Crosswater’s size. That idea will probably morph at the end; I think the town is a bit wider that this map implies. I’ll work that out once I get there.

If you’re more inclined to a top-down approach, this probably sounds like a terrible approach, in which case you should do what works for you. But if you prefer to work through the core of the story first and then fill in the rest, a map like this – bare-bones but with the important bits in the right place – can help you develop the flow of that story, rather than dictating it.

Fantasy Languages Need Not Apply

As you can see, Crosswater is lacking in polysyllabic and apostrophe-laden fantasy words, or even just words that aren’t in English. Part of this is a personal aesthetic; I tend to like portmanteaus, compound terms and colloquialisms much more than stuff in made-up languages. I can’t keep those words in my head when reading and can’t develop them in a logical sense when I write; better to work with word-components that actually engage me.

The other reason is thematic. Crosswater and the Westron Lands are meant to evoke Elizabethan London and England to some extent, although not exclusively. Using English words for place names helps with that, as so many locations of the period follow that model – and those that don’t are often derived from Roman or Celtic terms that were originally compound terms. (Manchester was basically called ‘breast-like hill’, at least according to Wikipedia.)

Not all of these words are set in stone. ’Courtpark’ isn’t going to last, because it sounds like something you find in a basketball game. My original plan was ‘Kingspark’ but that didn’t click either; it doesn’t pull apart cleanly into ‘King’s Park’ rather than ‘King Spark’. And ‘Dockside’ is a bit bland; I need to bring something in to spice that up. Time to pull out my reference books – the Vulgar Tongue, the amazing Macquarie Thesaurus and Liza Picard’s Elizabeth’s London – and see what grabs my eye.

Not all of these words are set in stone. ’Courtpark’ isn’t going to last, because it sounds like something you find in a basketball game. My original plan was ‘Kingspark’ but that didn’t click either; it doesn’t pull apart cleanly into ‘King’s Park’ rather than ‘King Spark’. And ‘Dockside’ is a bit bland; I need to bring something in to spice that up. Time to pull out my reference books – the Vulgar Tongue, the amazing Macquarie Thesaurus and Liza Picard’s Elizabeth’s London – and see what grabs my eye.

Bird’s Eye versus Boots on the Ground

This map is a useful tool in a lot of ways, especially as it helps me work out where all the various locations fit alongside each other.

But the map is not the territory, as they say, and this map – any map – doesn’t tell you or me what it’s like to live in Crosswater. It doesn’t say what the rivers smell like, how the food tastes, why the border between Greywharf and Wright’s Parish is erupting in violence; it doesn’t tell a story. Well, it doesn’t tell the story I want; maps can tell stories, but they are stories of grand scope and change, less stories about fist-fights with bronze cyborgs on collapsed bridges.

Evoking a location is something that happens in the text itself, rather than the map at the start. (Or at least it does if I do my job right.) That’s where the colour and shape comes out, where sights and sounds and smells enter play. But having said that, the birds-eye map still helps, because it shows you where that detail might be found. If I want to describe the feel of Dockside, I can see from the map that I need to reflect the presence of the harbour – the smell of the sea, the churn of the Dusk as it emerges into a nest of wharves, the warning bells as Warrant ferrymen take prisoners out to the jail of the Rock. Without a map to remind me, I might lose track of that – and that’s why my bodgy Word diagram is such a valuable tool.

In closing, Roland Emmerich’s Anonymous may have been awful trash, but it gave us some cool CGI visuals for Elizabethan London – so if you’re wondering what Crosswater looks like a bit lower to the rooftops, take the image below and add approximately 30% more masked superheroics and villainy. And some parkour. And maybe a giant snake. That’s pretty close.

September 5, 2013

Turn the map around

No time tonight for a proper mid-week post; there’s books to write, yard sale fodder to accumulate and pre-election stressing and disbelief to be had.

But I do want to ask one question for anyone/everyone reading:

What do maps mean to you?

Are they interesting? Tedious? Exotic? Mundane? Vital? Unnecessary ‘cos you have a smartphone? A glimpse of another place? A way to find a parking spot?

Over the next few weeks I’ll be talking a lot about maps, but before I do, have your say by leaving a comment. Get in early before Tony Abbott takes our posting privileges away.

September 1, 2013

A month of maps

I kind of hate maps.

This is another one of those things that make me a terrible nerd, like saying I’ve never watched any of the Star Trek TV shows or simply don’t care that much that Ben Affleck’s playing Batman in the next DC movie. Maps are one of those cornerstones of fantasy fiction, worlds sketched out in the opening pages of a book before a story starts, and I think most readers see them as a call to adventure, a sign that discoveries are ahead. But for me it’s always been the opposite; they make me less interested in a story, not more interested.

The late, great and sorely missed Diana Wynne Jones pretty much summed up my issue with maps in her wonderful The Tough Guide to Fantasyland:

Examine the Map. It will show most of a continent (and sometimes part of another) with a large number of BAYS, OFFSHORE ISLANDS, an INLAND SEA or so and a sprinkle of TOWNS. There will be scribbly snakes that are probably RIVERS, and names made of CAPITAL LETTERS in curved lines that are not quite upside down. By bending your neck sideways you will be able to see that they say things like “Ca’ea Purt’wydyn” and “Om Ce’falos.” These may be names of COUNTRIES, but since most of the Map is bare it is hard to tell.

These empty inland parts will be sporadically peppered with little molehills, invitingly labeled “Megamort Hills,” “Death Mountains, ”Hurt Range” and such, with a whole line of molehills near the top called “Great Northern Barrier.” Above this will be various warnings of danger. The rest of the Map’s space will be sparingly devoted to little tiny feathers called “Wretched Wood” and “Forest of Doom,” except for one space that appears to be growing minute hairs. This will be tersely labeled “Marshes.”

This is mostly it.

No, wait. If you are lucky, the Map will carry an arrow or compass-heading somewhere in the bit labeled “Outer Ocean” and this will show you which way up to hold it. But you will look in vain for INNS, reststops, or VILLAGES, or even ROADS. No – wait another minute – on closer examination, you will find the empty interior crossed by a few bird tracks. If you peer at these you will see they are (somewhere) labeled “Old Trade Road – Disused” and “Imperial Way – Mostly Long Gone.” Some of these routes appear to lead (or have lead) to small edifices enticingly titled “Ruin,” “Tower of Sorcery,” or “Dark Citadel,” but there is no scale of miles and no way of telling how long you might take on the way to see these places.

In short, the Map is useless, but you are advised to keep consulting it, because it is the only one you will get. And, be warned. If you take this Tour, you are going to have to visit every single place on this Map, whether it is marked or not. This is a Rule.

That last line in particular is what gets me – because what’s the point of putting something on the map if the story doesn’t examine that location? I look at a detailed map in a novel and all the suspense just drains out of the book for me, replaced by a dull expectation of ticking off checklist items. I get exhausted just thinking about the book ahead and its cavalcade of locations, landmarks and polysyllabic place names that I’ll no doubt have to encounter to get to the end.

Of course, that’s a very bottom-up way of thinking about it – that approach (which is how I write) doesn’t fill in detail until it’s needed, so if a detail is there then the implication is that it’s needed and thus will appear in the story. The top-down approach (going back to the discussion earlier this year on tops and bottoms oh my) is to start with the map and the world it depicts, designing all the little bits and pieces that go into it, then write your story around some of those bits, secure in the knowledge that if you need to move further afield to follow the narrative, there’ll be something there to ground the story.

Of course, that’s a very bottom-up way of thinking about it – that approach (which is how I write) doesn’t fill in detail until it’s needed, so if a detail is there then the implication is that it’s needed and thus will appear in the story. The top-down approach (going back to the discussion earlier this year on tops and bottoms oh my) is to start with the map and the world it depicts, designing all the little bits and pieces that go into it, then write your story around some of those bits, secure in the knowledge that if you need to move further afield to follow the narrative, there’ll be something there to ground the story.

As I do more worldbuilding for Raven’s Blood and think about the locations within and outside Crosswater… no, I’m still a bottom-up writer, and I still don’t really want to develop locations and ideas other than the ones I specifically need for my story. But nonetheless I’ve developed a better appreciation for the humble map, less as a finished piece of work and more as a writing tool I can use to develop a sense of place, character and internal logic for both my setting and my story as a whole. And I’ve started seeing a lot of different ways that tool can be applied – because a map can be a kind of Swiss Army knife of storycrafting, and the way you interact with that map as both reader and writer can really reshape the experience of the narrative.

The time has come for me to draw some maps. I have met the enemy and he is me. And Photoshop.

Anyway, the upshot of all of this is that maps have been on my mind for a while, and I have thoughts and opinions. SO MANY OPINIONS. Too many for one, two or maybe even three blog posts.

So instead I’m declaring September to be the month of maps here on the old blog, a time when I’ll be looking at maps and how we use them in fiction. And by ‘we’ I mean ‘me’ – I’ll be putting up posts (and maps) about Raven’s Blood, The Obituarist, Arcadia (remember that one?) and some of my gaming projects, looking at how each addresses its map differently and uses it for different purposes. Those will be the Sunday night posts; if I manage to do mid-week posts as well (I’ll try, but my spare time is bleeding away already) then I’ll try to present additional map discussions based around stuff from other writers and around the interwebs. And maybe you folks can also pipe up with some of your thoughts about maps, stories and narrative physicality – whatever the hell that phrase that I just made up means.

A month of maps. Let’s get lost.

August 25, 2013

Wiki wiki woo

So one of the things I did on my blogging holiday was write wiki entries.

WARNING

WARNING

WILD AND CRAZY GUY OVER HERE

Specifically, I was writing wiki entries for some of my roleplaying campaigns, and that little sound you can hear is all of my internet credibility squeaking out of my blog as if I was a balloon animal with a slow leak. But no, come back! This is writing-relevant! I doubleplus promise cross my heart!

So anyway, I have an account on Obsidian Portal, a useful gaming site that lets GMs create pages for their campaigns with images, NPC write-ups, session summaries and wikis. I’ve been running a single set of pages there for my D&D campaign since before it started, lo these many years ago, but recently I upped to a paid account so that I could set up a wiki for my Weird West Smallville game and for two campaigns I’ve planning to run once those finish.

Now, indulge me here, folks – go have a look at the pages and wikis for Exile Empire and Tribulation, the two campaigns that I’ve been running for a while. Potter around for a bit, click some links, read some adventure logs and – most importantly – take a brief pass through the wikis. Go on, I’ll wait.

Are we back? Good. Are we in awe about what an amazingly inventive GM and storycrafter I am in my games about fantasy adventurers and psychic cowboys?

…fine, whatever.

Now, pop quiz – what’s the big difference between the two campaign wikis? Anyone? That’s right, Exile Empire‘s is much larger and more detailed than Tribulation‘s – but most of that extra content hasn’t been at all relevant to the story (i.e. the game) that’s based on all that setting information. There’s a tonne of data about districts, factions and characters that have never appeared in the game; meanwhile, Tribulation‘s wiki has much less material, but all of it is directly relevant to the game.

And why? Because I wrote it after the game had actually started and we’d had all the core plot elements come out in play. Rather than trying to detail all the things that could be relevant, I just had to put in the things that definitely were relevant.

A wiki like Exile Empire‘s is a worldbuilding tool, specifically one aimed at the players of the game; it’s a way of putting everything that could be relevant to creating characters and understanding the world out for their perusal, so that they can explore it, internalise it and come up with ideas of how to use it. It’s a great tool for coming up with the ideas for stories and allowing you to explore those ideas and their connections in a little more depth before picking out those you’ll actually use. You can also see this in the detailed wiki I created for Annihilation, the Marvel Heroic RPG campaign I plan to run when Exile Empire is finished. (Go on, click the link, you know you want to.) Again, lots of information, lots of connections between information – but because the game hasn’t started yet, none of it links up to any story. It’s all potential, all background data for the players to use; all stage, no direction.

The benefit of a wiki like this comes from reading it, whether that’s for players to get character ideas or for me to think ‘okay, let’s come up with a story involving House Tharashk and the Storm Hammers in the Harbour District’ and have that idea drive play for like a year.

The Tribulation wiki, on the other hand, is more of a story development tool. It’s free of any extraneous material and it’s not very handy for developing the world; it’s probably not very interesting reading, even as far as RPG campaign wikis go, because it’s so focused on the essentials. But writing it helped me get a better understanding of how the plot elements I’d already introduced fit together, and in doing so I came up with more ideas of how to progress with those ideas towards the game’s conclusion. So while this wiki maybe isn’t as useful to my players, it’s been very useful to me. I have another game on there, Tales of New Jerusalem, which also has a sketchy wiki, and I’m doing that deliberately so that I don’t overplan or include too much extraneous worldbuilding in the game. Instead I want to focus on short story arcs and connections between multiple characters, and my experience with Tribulation suggests to me that I’ll handle this better if I come back to the wiki after a few plots have already been laid down and explored in play.

The benefit from a wiki like these comes from writing it, from actually sitting down and clearly outlining story elements and their connections; it lets me think ‘there definitely should be connections between the Apache Super-Chief, Delian Sisula and Emmett’ and then develop those connections in the next story arc.

–

So game nerding aside, what’s the upshot of all this for writing? Two things:

Using a wiki to outline all the possibilities for your story can help you determine which ones you want to explore before you write.

Using a wiki to clarify the connections between plot elements can help you work out where you’re going as you write.

In the early stages of working out the parameters of a story, the kind of exhaustive worldbuilding of a wiki like those for Exile Empire or Annihilation can be really useful – it helps you visualise all the things your story could have in it, then pick out the elements that it actually will have in it, leaving the rest to fade into the background of your mind until they’re needed (if ever). It’s especially valuable for complex worlds that have lots of information in them that readers need to know about; you can see the elements and how to work them into the story.

Writing a wiki in the middle of the story, though, helps you work out what you’ve missed so far and where to take things from here. A lean, sparse wiki like those of Tribulation or New Jerusalem can help visualise the shape of the story so far. Actively spelling out connections between story elements can help you make sense of where you’ve been and where you’re going; it can also show you if those connections need to be explored more in the story, whether going forward or by editing them back into what’s already been written.

Both approaches have plusses and minuses, and both are just one possible example of using an outlining and interconnectivity tool; wikis are one option but they’re not the only ones. Mind maps, flowcharts, stacks of index cards… there are lots of ways to visualise and connect your story elements. You don’t need to use such things – as always, there’s no One True Way to write effectively – but spilling everything out in front of you and connecting the dots can be a big help in marshalling your ideas, whether they’re ideas about what to do in the first place or about where to go from here.

Give it a try; if nothing else, you might find it fun. Certainly if you’re the kind of person who likes sitting alone in a darkened office, cross-referencing notes on the X-Men’s activities in the Kree Empire and seeing how that affects their trip to the Forgotten Realms.

OH DAMN I CROSSED THE STREAMS

August 18, 2013

What we write about when we write about grief

It’s been a rough week.

As per the last post, our cat Graeme – the subject of a number of posts here over the last couple of years – died on Thursday. He gave a posthumous goodbye to his many fans over on his Facebook page (yes, really), and I made a follow-up post to talk about what he meant to us.

As per the last post, our cat Graeme – the subject of a number of posts here over the last couple of years – died on Thursday. He gave a posthumous goodbye to his many fans over on his Facebook page (yes, really), and I made a follow-up post to talk about what he meant to us.

Some people might feel that it’s perhaps a bit mawkish to mourn a dead pet so strongly; it’s not as if I’ve lost a friend or a parent. But I’ve lost both those things as well, and I can tell you that grief is grief is grief. It may come in different serving sizes, but it’s all the same meal of sadness and ashes. And it always tastes the same.

I’ve said my piece about Graeme already, and I don’t really feel like using this space to display my feelings any more than I already have. This is a writing blog, so let’s talk about writing. Let’s talk about that old adage of ‘write what you know’.

–

As I’ve said a few times before, too many writers misinterpret this to be a statement about real-world expertise; computer programmers should write stories focusing on computer programming, farmhands should write novels set on farms with stump-jump plough racing and so on. But how boring a world would it be if we could only write stories that mimicked our own quotidian experiences and nothing else? It’d be like every novel was just your LinkedIn profile with added dialogue.

Instead, I think ‘write what you know’ is about drawing on your experience as a human being, not just a tinker/tailor/soldier/celebrity bounty hunter. Our emotional experience of life is unique, but at the same time it’s bound to overlap with almost everyone else’s, and by grounding your writing in your overlap your work is more likely to resonate with the reader. We might not know what it’s like to endure vampire poison or cybernetic surgery, but we know what it’s like to get sick or injured and how we feel as we recover. We probably haven’t encountered a ghost, but we know what it’s like to be frightened; we haven’t been in a firefight with terrorist cybergorillas, but we know what it’s like to be panicked, full of adrenaline and making snap decisions.

And unless we’re very young or very lucky, we all know what it’s like to lose someone we love.

–

Adventure genre fiction is, on the whole, not very interested in writing about grief, or shame, sadness, regret and similar feelings. Genre stories tend to be external, plot-driven narratives, and calling a halt to the action to spend a chapter privately mourning the minor character who got shot on page 200 is unlikely to provide a satisfying experience for 99% of readers. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t find the space within a story to explore some of those emotional underpinnings, some of the small moments that come when the pace slows down and the adrenaline wears off. Because those emotions ground the moment and remind the reader that this is a story about people, and that we all share in the human condition in some way – yes, even if your story isn’t actually about humans.

Adventure genre fiction is, on the whole, not very interested in writing about grief, or shame, sadness, regret and similar feelings. Genre stories tend to be external, plot-driven narratives, and calling a halt to the action to spend a chapter privately mourning the minor character who got shot on page 200 is unlikely to provide a satisfying experience for 99% of readers. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t find the space within a story to explore some of those emotional underpinnings, some of the small moments that come when the pace slows down and the adrenaline wears off. Because those emotions ground the moment and remind the reader that this is a story about people, and that we all share in the human condition in some way – yes, even if your story isn’t actually about humans.

I won’t be writing novels about my cat, my father or the other people I’ve lost; those are my stories, no-one else’s. But I’m taking what I’ve learned from those stories and making use of them in Raven’s Blood, using them to make Kember’s story of losing her mother (and more) feel genuine and emotionally real. Just as I’ll use my other experiences of anger, fear and desperation – as well as some positive experiences too, sure – to try to help readers connect to the dangers and adventures in the book.

No matter your story, this is one of the best ways to make it come alive. Dip into your own life, your own feelings, and put that experience on the page. If it feels real to you – if it hurts you to write it, even just for a moment – then odds are it’ll feel real to the reader too.

–

And yes, all of this hurt to write too. Just a little.

But I’d rather hurt than forget.

Now to move on.

August 15, 2013

Our cat Graeme died this morning.

This is all I can say f...

August 11, 2013

And we’re back

*yawn*

*stretch*

*checks alarm clock*

OH HELL, I OVERSLEPT

…I mean, here I am, back just as promised!

So, did you miss me?

It’s been a hectic emotional rollercoaster, these last two months, full of doing stuff and learning things and not blogging. But my batteries have recharged, my notepad is full of ideas for blog posts (one of which just says ‘Doom Cock’, but I’m sure it’ll make sense eventually) and I have news and opinions to share once more. I’m glad that y’all hung around during the downtime.

So, let’s have a quick essay on what I did on my winter holidays.

I wrote stuff! Which is good, as that was the whole point of taking the break. I worked on Raven’s Blood, which is still behind where I would like it to be, but I’m very happy with the material I’m writing – so if I take more time but create a more polished draft, that’s probably a win. I’d still like to have it finished or close to finished by the time GenreCon comes around in October, though. I also did other writerly things, such as a freelance editing project and creating some wikis for various time-wasting nonsense activities.

I appeared at PAX Australia! I thought our panel on writing RPGs would get about 10 people, but it was more like 200 and another 50-odd standing outside. Crazy! I think it went well, and the feedback was very positive, so that was great. Overall I was pretty impressed with PAX – well, at least as far as the space and support they gave for tabletop gaming. Most of the videogame stuff left me cold, and I agree with Ben McKenzie that a lot more needs to be done to improve the stance PAX and the Penny Arcade founders take on problematic elements in gaming. PAX was also where I announced my return to the world of RPG writing, as I’ll be working on a product for a setting dear to my heart over the next few months or so. More details to come soon!

I also appeared at the helm of @WritersRotation – a curated Twitter account where a different writer tweets each week. That was fun, and hopefully some of the account’s followers will come by the blog and check out what I’m like on an ongoing basis. (Spoilers: drunk and full of excuses, mostly.)

I read some cool books! Specifically, I read Nick Harkaway’s Angelmaker, which is just a wonderful absurd romp, a riot of London crooks, aging spies, robot bees, pulp adventure and the uncertainty principle. I also read Margo Lanagan’s Sea Hearts, which is just about the exact opposite – an emotionally wrenching story about spurned and idolised women, long grudges and longer sadness, and one of the most moving and gruelling stories I’ve read in a long time. And YA at that – kids these days start the hard stuff young. And I started Chuck Wendig’s The Blue Blazes, read a bunch of comics, saw some adequate films (and one goddamn awful one), watched cartoons… you know, the usual stuff.

I quit my day job! Not to write full-time, no – one day, yes, but not today. Instead I’m moving on after seven years – seven years! – in educational publishing to a new and exciting role in… well, in educational publishing, but of a different type and for a different market. It’s a big move, and in many ways a difficult one; you don’t work in one place for so long without putting down roots. Still, I’m really pumped for the new job, which starts in two weeks. Here’s hoping that a) I enjoy it, b) they decide to keep me and c) it leaves me with the time and energy for writing.

I lived my life! I ran some games, I saw some shows, I drank some drinks. You know, quotidian stuff like that. And I learned that our cat’s health is fading. That wasn’t such good news, and it’s been hard for all of us here to accept that and make decisions about what to do about it. He’s still with us – he’s sitting on my lap right now – but he won’t be at some point. Which is also part of living life, I guess. So it goes.

Stories begin. Stories end. Stories go on.

And on that note, this story is done for the evening. It’s good to be back on the word wagon. Thanks for sticking with the ride.