Rob Kitchin's Blog, page 41

March 29, 2019

Review of The Girl Without Skin by Mads Peder Nordbo (2018, Text Publishing)

Matthew Cave is a journalist in the small town of Nuuk in Greenland. Although born in Greenland he grew up in Denmark and has only recently moved there after the death of his pregnant girlfriend in a car accident. When a mummified body is discovered in a crevasse on an ice sheet he is sent to cover the story as it appears that it is a 400 year old Viking. The next day the mummy is gone and the policeman guarding it has been found dead. The policeman’s death is strangely similar to a series of murders in the 1970s when four fathers suspected of committing child abuse were found flayed and their stomachs cut open and entrails pulled out. Matt starts to investigate the historical deaths, but soon realises that his actions have unearthed secrets others would prefer kept suppressed. Joining forces with a young Inuit woman, Tupaarnaq, recently released from prison for manslaughter, having been convicted for killing her parents and two sisters, he keeps digging despite the risks.

Matthew Cave is a journalist in the small town of Nuuk in Greenland. Although born in Greenland he grew up in Denmark and has only recently moved there after the death of his pregnant girlfriend in a car accident. When a mummified body is discovered in a crevasse on an ice sheet he is sent to cover the story as it appears that it is a 400 year old Viking. The next day the mummy is gone and the policeman guarding it has been found dead. The policeman’s death is strangely similar to a series of murders in the 1970s when four fathers suspected of committing child abuse were found flayed and their stomachs cut open and entrails pulled out. Matt starts to investigate the historical deaths, but soon realises that his actions have unearthed secrets others would prefer kept suppressed. Joining forces with a young Inuit woman, Tupaarnaq, recently released from prison for manslaughter, having been convicted for killing her parents and two sisters, he keeps digging despite the risks. Set in Greenland, The Girl Without Skin is the first book in a new series by Greenland-based, Danish writer Mads Peder Nordbo. The lead character is Matthew Cave, a journalist mourning the death of his pregnant wife who finds himself investigating two murder inquiries that spans two periods, 1973 and 2014. The story is told through two parallel threads. One follows the original police investigation in 1973, the other Cave’s contemporary investigation which is guided by the notebook of one of the policeman from the earlier period. The common links are men being brutally murdered and the discovery of a mummified body. The mummified body and Cave’s actions resurfaces old secrets and a political conspiracy that some want to remain hidden, placing Cave in danger, his fate eerily echoing that of the policemen in 1973. He is aided by the girl without skin, a local Inuit woman recently released from prison who’s body is entirely covered with tattoos. The start of the book feels a little clunky, which I initially felt was a translation issue but probably wasn’t; rather it was a handful of obvious plot devices to set up premises and plot trajectory. After that, it seemed to work fine, providing a social commentary on Greenland’s patriarchal society and political commentary on its relationship to Denmark. There’s a good sense of place and the twin narratives work well together, spinning out an interesting tale and creating some tension and mystery, with a nice twist near the end.

Published on March 29, 2019 04:03

March 26, 2019

Review of Sweetpea by C.J. Skuse (2017, HQ)

Rhiannon Lewis is 27 and living her life as an act. As a child she survived a mass killing and became something of a celebrity. As an adult she works at a local newspaper, dates Craig, a builder who is cheating on her, and hangs around with her bitchy friends from school. While she plays nice, she’d like to kill them all. In fact, she’d like to kill everyone who annoys her. And she likes to kill. After a three year hiatus, she murders a would-be rapist. A few weeks later she kills another. Nobody suspects the violent deaths could be performed by a woman, which emboldens her further. The local paper calls the killer, ‘The Reaper’, but she calls herself ‘Sweetpea’.

Rhiannon Lewis is 27 and living her life as an act. As a child she survived a mass killing and became something of a celebrity. As an adult she works at a local newspaper, dates Craig, a builder who is cheating on her, and hangs around with her bitchy friends from school. While she plays nice, she’d like to kill them all. In fact, she’d like to kill everyone who annoys her. And she likes to kill. After a three year hiatus, she murders a would-be rapist. A few weeks later she kills another. Nobody suspects the violent deaths could be performed by a woman, which emboldens her further. The local paper calls the killer, ‘The Reaper’, but she calls herself ‘Sweetpea’.Sweetpea is a fresh-take on the serial killer genre. A macabre, black comedy that is styled as Bridget Jones meets Hannibal Lecter. Rhiannon Lewis keeps a diary. Each day she lists all the people she would like to kill and how her day unfolds. She charts the progress of her Act – the charades she plays out to persuade people that she’s a normal, 27 year old woman – and her real thoughts, which are a tirade of sarcastic, funny and hateful observations and actions. On wandering home from a night out she kills a would-be rapist. She hasn’t killed for three years, but the event re-ignites her passion for extinguishing lives, especially those that abuse women and children. So starts a murderous spree. Initially I was taken with the voice and style, which is over-the-top bawdy, alternative, dark, and challenges political correctness (think Men Behaving Badly, Bottom, Black Books), and made me laugh out loud several times. Rhiannon is an interesting character, consciously playing a role while living a double life. She’s pitched somewhat as an anti-heroine, fighting sex offenders. The problem for me is that she’s actually just a killer with a very wonky moral compass and as the book progressed the humour, her story, her friends and work colleagues became increasingly tedious, despite there still being some laugh-out loud moments. The narrative simply felt too stretched out, with the story not really progressing much for a couple of hundred pages, and the ending was somewhat anti-climactic, ending mid-denouement (obviously to try and pull the reader to the next instalment – I don’t mind ambiguous endings, but just stopping mid-scene is annoying). By this stage, it was clear that Rhiannon had little heroine qualities; and in some ways that was the most interesting thing as a reader – the way that Skuse uses black comedy to try and create a bond between reader and a psychopathic woman. And it kind of works for a while, but then ran out of steam.

Published on March 26, 2019 00:03

March 24, 2019

Lazy Sunday Service

A week of marking, writing, and reading mostly academic articles. I'm trying to read my way into a new area which always seems a little bit of an uphill trek. On the fiction front, I'm working my way through Mads Peder Nordbo's The Girl Without Skin set in Greenland in 1973 and 2014.

A week of marking, writing, and reading mostly academic articles. I'm trying to read my way into a new area which always seems a little bit of an uphill trek. On the fiction front, I'm working my way through Mads Peder Nordbo's The Girl Without Skin set in Greenland in 1973 and 2014.My posts this week

Review of Kaddish in Dublin by John Brady

Review of Bloody January by Alan Parks

Reeling-in

Published on March 24, 2019 02:02

March 23, 2019

Reeling-in

Sarah looked up from the screen. ‘He’s actually going to do this.’

‘There’s still two kilometres left and they’re reeling him in.’

‘I know, but …’

‘He needs to grind out that big gear. Come-on, Matt!’

‘When we bought him that first bike who’d have thought he might win a major race?’

‘He hasn’t won it yet.’

‘He was terrified of us taking the stabilisers off.’

‘He’s going to do this!’

‘Somebody’s jumped off the front.’

‘They’ve left it too late. Come-on!’

‘I can’t watch.’

‘It’s going to be close.’

‘Well?’

‘One hundred metres. Oh, god. Yes! By a wheel-rim!’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

‘There’s still two kilometres left and they’re reeling him in.’

‘I know, but …’

‘He needs to grind out that big gear. Come-on, Matt!’

‘When we bought him that first bike who’d have thought he might win a major race?’

‘He hasn’t won it yet.’

‘He was terrified of us taking the stabilisers off.’

‘He’s going to do this!’

‘Somebody’s jumped off the front.’

‘They’ve left it too late. Come-on!’

‘I can’t watch.’

‘It’s going to be close.’

‘Well?’

‘One hundred metres. Oh, god. Yes! By a wheel-rim!’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

Published on March 23, 2019 01:59

March 22, 2019

Review of Kaddish in Dublin by John Brady (1990, Harper Collins)

The body of a journalist is washed up on the Dublin shoreline. He is the son of a prominent, well-connected judge, who is also a member of the city’s small Jewish community. A small, unknown Palestinian group claim responsibility for the murder. The judge requests that Inspector Matt Minogue of the Murder Squad is placed in charge of the investigation. Minogue has to contend with navigating the religious landscape of the city, both Jewish and Catholic, and also the internal politics of the police, reporting to the Garda Commissioner and collaborating with Special Branch given the potential political nature of the case. As he slowly makes headway, he senses he might be dealing with a conspiracy much closer to home that has potentially far-reaching consequences.

The body of a journalist is washed up on the Dublin shoreline. He is the son of a prominent, well-connected judge, who is also a member of the city’s small Jewish community. A small, unknown Palestinian group claim responsibility for the murder. The judge requests that Inspector Matt Minogue of the Murder Squad is placed in charge of the investigation. Minogue has to contend with navigating the religious landscape of the city, both Jewish and Catholic, and also the internal politics of the police, reporting to the Garda Commissioner and collaborating with Special Branch given the potential political nature of the case. As he slowly makes headway, he senses he might be dealing with a conspiracy much closer to home that has potentially far-reaching consequences.Kaddish in Dublin is the third book in the Matt Minogue series. To my mind, the series is one of the strongest Irish police procedural series set in the South, though the tenth and last book was published in 2009. The books are straight-up procedurals rooted in the realism of everyday life, Irish society at the time, and institutional politics, with little melodrama or over-the-top action, and police officers who are ordinary people rather than having some traumatic back story. In this sense, the books are more Scandinavian in style than most US or UK contemporary series, but with a good dose of Irish humour and under-statement thrown in. This outing focuses on the death of a Jewish journalist and a political conspiracy. Set in the late 1980s and given the power of the Church at that time and political conservatism and scandals, the conspiracy didn’t feel outlandish. In fact, given the era it was written in, the topic seems quite a brave choice to focus on. Minogue goes about his business in his usual way, patiently uncovering clues and rattling cages while worrying about the consequences, and fretting over his family. There is a strong sense of place and the dialogue, in particular, is excellent. Overall, an enjoyable murder mystery with a political edge.

Published on March 22, 2019 02:09

March 19, 2019

Review of Bloody January by Alan Parks (2017, Canongate)

Glasgow, 1973. Detective Harry McCoy is told by a violent criminal in the city’s prison that a young woman is to die by the morning. After a drunken night, and with his new partner in tow, McCoy waits at the bus centre for the young woman’s bus to arrive. When it does a teenage boy shoots the woman dead then turns the gun on himself. The boy worked in the grounds of the Dunlops, a rich, well-connected family, one that is well-known to McCoy. He had a run-in with them a couple of years ago, his former police partner now works security for them, and the mother of his dead child lives in their house. After making a hames of his visit the Dunlops, McCoy’s boss constrains his investigation. McCoy is soon trailing round brothels and homeless hangouts trying to find other leads, but he’s sure the Dunlops are involved somehow even if they appear untouchable and few people are willing to help. He also has other problems, namely a psychotic gang leader, Stevie Cooper, who will occasionally help out his boyhood friend, but always at a heavy price.

Glasgow, 1973. Detective Harry McCoy is told by a violent criminal in the city’s prison that a young woman is to die by the morning. After a drunken night, and with his new partner in tow, McCoy waits at the bus centre for the young woman’s bus to arrive. When it does a teenage boy shoots the woman dead then turns the gun on himself. The boy worked in the grounds of the Dunlops, a rich, well-connected family, one that is well-known to McCoy. He had a run-in with them a couple of years ago, his former police partner now works security for them, and the mother of his dead child lives in their house. After making a hames of his visit the Dunlops, McCoy’s boss constrains his investigation. McCoy is soon trailing round brothels and homeless hangouts trying to find other leads, but he’s sure the Dunlops are involved somehow even if they appear untouchable and few people are willing to help. He also has other problems, namely a psychotic gang leader, Stevie Cooper, who will occasionally help out his boyhood friend, but always at a heavy price.Detective Harry McCoy is an anti-hero cop cut from a familiar set of tropes – a man who grew up in institutional care, who’s boyhood friend is a major criminal, who’s own child died young, who has a drink and authority problem, is a Catholic in a sectarian institution, and who regularly strays beyond the bounds of acceptable policing practice. He has a moral compass of sorts and believes in justice, even if it’s occasionally rough in nature. In this first book in the series he’s investigating the murder of a young prostitute who seems to have been catering for violent tastes. He suspects a link to a rich family, but has been warned to stay away. But Harry isn’t very good at following orders and his new partner, Wattie, seems prepared to tolerate his unorthodox methods. It seems, however, that he’s straying too far from the path, both professionally and personally, as he mixes with criminals and prostitutes and habitually gets drunk and takes soft drugs, as well as taking regular beatings. It’s a good job he’s got a semi-understanding boss that he respects. Parks spins the tale in a hardboiled style, keeps the story moving at a decent clip, and does a good job of capturing Glasgow in 1973 and the criminal underbelly of the city. There’s no great surprise in the resolution, but that matters little as it’s as much a tale about the journey as destination. Overall, a well told, dark slice of Scottish noir.

Published on March 19, 2019 04:25

March 17, 2019

Lazy Sunday Service

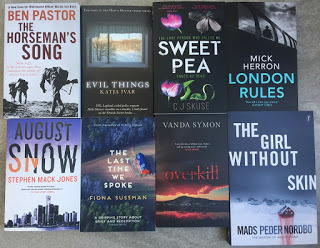

A busy week of travel with trips to London and Tilburg in the Netherlands. Arrived home to find an order of books had arrived at the local bookshop. The TBR has crept up in size in recent months, so will splice these into the mix. Looking forward to reading in due course.

A busy week of travel with trips to London and Tilburg in the Netherlands. Arrived home to find an order of books had arrived at the local bookshop. The TBR has crept up in size in recent months, so will splice these into the mix. Looking forward to reading in due course.My posts this week

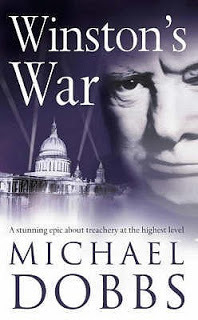

Review of Winston’s War by Michael Dobbs

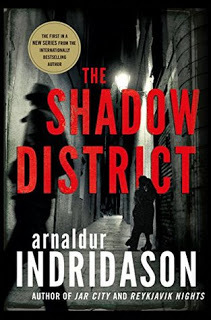

Review of The Shadow District by Arnaldur Indridason

Most read authors

Falling

Published on March 17, 2019 04:29

March 16, 2019

Falling

The world was amazing from this height; spread out like an enormous map.

Conor was diving in, his arms outstretched.

They linked up; smiled at each other.

A minute later they separated and Annie released her parachute.

It deployed but didn’t properly unfurl. The secondary chute failed to appear.

Conor was below her, still falling. Then his chute opened.

She was catching up; screaming his name.

At first he thought he’d missed her, but then managed to snag the collapsed canopy.

She was crying and laughing, hope blossoming.

Then she was falling again.

Knowing now why her chute had failed.

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

Conor was diving in, his arms outstretched.

They linked up; smiled at each other.

A minute later they separated and Annie released her parachute.

It deployed but didn’t properly unfurl. The secondary chute failed to appear.

Conor was below her, still falling. Then his chute opened.

She was catching up; screaming his name.

At first he thought he’d missed her, but then managed to snag the collapsed canopy.

She was crying and laughing, hope blossoming.

Then she was falling again.

Knowing now why her chute had failed.

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

Published on March 16, 2019 11:34

March 14, 2019

Review of Winston’s War by Michael Dobbs (2002, HarperCollins)

1938. Winston Churchill is in the political wilderness and almost bankrupt. In his wake is a series of political disasters, he’s bet heavily on the stock exchange, and his anti-appeasement rhetoric is deeply unpopular with colleagues and the public. Churchill though has little time for the opinion of others; he can see another war looming and the actions of Chamberlain and Halifax are not going to divert that but rather leave Britain unprepared. Guy Burgess is a journalist for the BBC. He shares Churchill’s view and he wants to help the politician. Burgess has plenty of dodgy contacts, including a barber who cuts the hair of senior politicians and civil servants and is privy to private conversations, as well as access to money to alleviate Churchill’s debts. The two men meet on October 1st 1938. Eighteen months later Britain is at war, Churchill, despite the odds, has succeeded Chamberlain, and Burgess has burned bridges with the new prime minister. The rest is history.

1938. Winston Churchill is in the political wilderness and almost bankrupt. In his wake is a series of political disasters, he’s bet heavily on the stock exchange, and his anti-appeasement rhetoric is deeply unpopular with colleagues and the public. Churchill though has little time for the opinion of others; he can see another war looming and the actions of Chamberlain and Halifax are not going to divert that but rather leave Britain unprepared. Guy Burgess is a journalist for the BBC. He shares Churchill’s view and he wants to help the politician. Burgess has plenty of dodgy contacts, including a barber who cuts the hair of senior politicians and civil servants and is privy to private conversations, as well as access to money to alleviate Churchill’s debts. The two men meet on October 1st 1938. Eighteen months later Britain is at war, Churchill, despite the odds, has succeeded Chamberlain, and Burgess has burned bridges with the new prime minister. The rest is history.In Winston’s War, Michael Dobbs tells the story of Winston Churchill’s rise to power, concentrating on the eighteen months between his meeting with Guy Burgess, later infamous for being unmasked as a Soviet spy, to when he takes office. Given Churchill’s marginal political position in 1938 and the fact that very few politicians in his own party, let alone the opposition, wanted him to become prime minister even at the point that he does (Halifax was the preferred option), that he gained control was a minor miracle. Or as Michael Dobbs portrays it, a fortuitous set of events and a lot of political skulduggery, aided by the actions of Hitler and Mussolini. Reading the book as the UK political system implodes with Brexit was interesting as there are many parallels – Britain’s relationship with Europe, bitter political infighting in the Tory party, the media throwing shapes. Dobbs’ story blends the historical record with fiction to tell Churchill’s tale, focusing on the underhand actions of both Churchill and Chamberlain as they vie for power, throwing in the role of Guy Burgess, who has been airbrushed from the history of the early years of the war. It’s a very readable and engaging tale, if a little over-long at 690 pages. As with similar books, I’m always a little hesitant about history as fiction, as it’s difficult to know what actually happened and what is pure fantasy, especially when just about every character was a real person. Nonetheless, an entertaining political story about a critical moments in British history.

Published on March 14, 2019 01:47

March 12, 2019

Review of The Shadow District by Arnaldur Indridason (2017, Vintage; Icelandic 2013)

1944, Reykjavik. A young woman’s body is discovered behind the new national theatre, currently being used as a store by the occupying allied forces. The murder is investigated by a local detective, Flovent, and a Canadian military policeman with Icelandic roots, Thorsen. Their initial suspects are an American soldier and his Icelandic girlfriend who discovered the body and fled the scene, but their investigation soon moves on. The present day, a ninety year old man is found suffocated in his bed. In the house are newspaper cuttings related to the war time case. A retired detective, Konrad, remembers the case having grown up in the district and his father trying to profit from it. He starts his own investigation with the blessing of the police, tracking the last movements and actions of the dead man and simultaneously trying to piece together the original war-time case.

1944, Reykjavik. A young woman’s body is discovered behind the new national theatre, currently being used as a store by the occupying allied forces. The murder is investigated by a local detective, Flovent, and a Canadian military policeman with Icelandic roots, Thorsen. Their initial suspects are an American soldier and his Icelandic girlfriend who discovered the body and fled the scene, but their investigation soon moves on. The present day, a ninety year old man is found suffocated in his bed. In the house are newspaper cuttings related to the war time case. A retired detective, Konrad, remembers the case having grown up in the district and his father trying to profit from it. He starts his own investigation with the blessing of the police, tracking the last movements and actions of the dead man and simultaneously trying to piece together the original war-time case. The Shadow District is the first book in a new series by Arnaldur Indridason charting the cases of Flovent and Thorsen and set in war-time Iceland. Somewhat unusually, this first instalment concerns their last case together before Thorsen moves on with the occupying army to continental Europe then returning to Canada, and also has a second main thread set sixty five years or so later. The story pivots between the two periods tracking the investigation into the murder of young woman in 1944 and the death of an elderly man decades later. The lynch-pin is Konrad, a retired CID detective, who remembers the original case as a child and is intrigued by the man’s suspicious death. As such, there are two police procedural tales being told in parallel, with the chapters alternating between the two periods as Flovent and Thorsen work their investigation and Konrad also re-pieces it together as he tries to work out the connections across time and people between the cases. As usual, Indridason tells the tale in an under-stated way without relying on overly-contrived plot devices or melodrama, letting the two stories unfold in a credible and engaging way. The result is an intriguing story populated with realistic characters, scenarios and police work, with a strong sense of place and time.

Published on March 12, 2019 02:30