Rob Kitchin's Blog, page 37

June 15, 2019

What kind of question is that?

‘Fifty kinds of love? Seriously, why do you read these things?’

Matt threw the magazine onto the floor and dropped on the sofa.

Chloe crossed her legs and glared at him. ‘Because they entertain. They enlighten. They comfort.’

‘Comfort?’

‘Yes, comfort. They let you know that you’re not the only woman living with a Neanderthal.’

‘You needed a magazine for that?’

‘Matt, do you love me?’

‘What kind of question is that?’

‘A pointed one.’

‘Because I criticised your magazine?’

‘Because you don’t understand why I read them.’

‘This is ridiculous.’

‘What’s ridiculous is that you haven’t answered the question.’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

Matt threw the magazine onto the floor and dropped on the sofa.

Chloe crossed her legs and glared at him. ‘Because they entertain. They enlighten. They comfort.’

‘Comfort?’

‘Yes, comfort. They let you know that you’re not the only woman living with a Neanderthal.’

‘You needed a magazine for that?’

‘Matt, do you love me?’

‘What kind of question is that?’

‘A pointed one.’

‘Because I criticised your magazine?’

‘Because you don’t understand why I read them.’

‘This is ridiculous.’

‘What’s ridiculous is that you haven’t answered the question.’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

Published on June 15, 2019 03:08

June 14, 2019

Review of Code Breaker by Marc McMenamin (2018, Gill)

During the Second World War Ireland declared itself neutral and sought to stay out of the conflict. Its strategic location on the edge of the Atlantic and sharing a land border with Britain meant it was under pressure from both the Allies and Germany to favour and aid their cause. As McMenamin details, while the Irish government cooperated covertly with the British, especially on intelligence work and enabling flights over Donegal, it stuck rigidly to neutrality with Germany. The government maintained diplomatic relations and let its legation operate throughout the war, but also actively policed spying and jailed German spies, and sought to limit German influence on domestic politics and activities that might lead to the Allies to occupy the country. The IRA, on the other hand, hoped collaboration with Germany might lead to a united Ireland and the organization actively aided German spies sent to Ireland, notably Hermann Gortz. In response, section G2 of the Irish intelligence service sought to actively limit German communications and capture spies, and the Irish government interred IRA members. The Abwehr and SD sent a relatively small number of spies to Ireland including a handful of Irish nationals, a couple of South Africans, and an Indian. All but Gortz were caught shortly after landing or never made it ashore, and most seemed ill-suited to the task with the exception of Gortz and Gunther Schutz.

During the Second World War Ireland declared itself neutral and sought to stay out of the conflict. Its strategic location on the edge of the Atlantic and sharing a land border with Britain meant it was under pressure from both the Allies and Germany to favour and aid their cause. As McMenamin details, while the Irish government cooperated covertly with the British, especially on intelligence work and enabling flights over Donegal, it stuck rigidly to neutrality with Germany. The government maintained diplomatic relations and let its legation operate throughout the war, but also actively policed spying and jailed German spies, and sought to limit German influence on domestic politics and activities that might lead to the Allies to occupy the country. The IRA, on the other hand, hoped collaboration with Germany might lead to a united Ireland and the organization actively aided German spies sent to Ireland, notably Hermann Gortz. In response, section G2 of the Irish intelligence service sought to actively limit German communications and capture spies, and the Irish government interred IRA members. The Abwehr and SD sent a relatively small number of spies to Ireland including a handful of Irish nationals, a couple of South Africans, and an Indian. All but Gortz were caught shortly after landing or never made it ashore, and most seemed ill-suited to the task with the exception of Gortz and Gunther Schutz.McMenamin provides a relatively broad account of Ireland’s relationship with Germany and Britain and its quest to remain neutral, focusing on the various spies Germany sent to Ireland and the work of G2. In particular, he spends some time detailing the work of Richard Hayes, the Director of the National Library, who was recruited on a part-time basis by G2 to crack German ciphers and help interrogate prisoners. Hayes was a polymath, skilled as both a linguist and a mathematician. His approach to cryptography was mathematical, but also social and technical, spending time talking to spies, riflling through their possessions for clues, and using forensics on burned paper. He made a number of contributions to cracking German ciphers including being the first to identify the use of microdots and solving agent in-field radio and legation ciphers, the latter of which were used in the Ardennes offensive. After the war his work was officially recognized in a secret meeting with Churchill and MI5, and he continued as director of the National Library until 1967 when he took up a position of librarian for the Chester Beatty Library.

While the book is nicely written and interesting, it’s timeline jumps around a bit, much of the material about German spies in Ireland has been told previously, and the new focus on Hayes is a little thin, in part due to the lack of source material. It would have also been nice to get more technical explanation of how the ciphers worked and were cracked, and the text linked to its sources. It would have also been preferable if the hyperbole could have been dropped. Hayes work was important, and his story worth telling, but he was not all that ‘stood between Ireland and Nazi Germany’ and ‘the fate of the country and the outcome of the war’ did not rest ‘on his shoulders’. His work was far from ‘crucial’ to the war (though it no doubt influenced Irish position and policy), and had marginal effect on turning the tide in the Allies favour (by late 1944 the tide had long turned). And some statements simply don’t stack up. Gortz was arrested in November 1941 and the idea he could have tipped the Germans to the double-cross system or the plans to land in Normandy as claimed make little sense. This hyperbole aside the book provides a readable overview of Ireland’s approach to Germany and its spies and the efforts of Richard Hayes and his G2 colleagues.

Published on June 14, 2019 12:54

June 11, 2019

Review of London Rules by Mick Herron (2018, John Murray)

A terrorist attack in Derbyshire and a pro-Brexit MP with designs on his job and a tabloid journalist for a wife has the Prime Minister on his toes, and by association Claude Whelan the new head of the Secret Service. Whelan will soon have more trouble to deal with, including a Muslim MP who is acting strangely and his own service being implicated in the attack. Slough House, the dumping ground for washed up spies, is never far from the Secret Services woes and one its occupants soon find themselves the target of a murder and the team chasing terrorists despite them supposedly being locked-down. Slough House might be home to the slow horses - capable of making any situation worse - but they still play with London Rules.

A terrorist attack in Derbyshire and a pro-Brexit MP with designs on his job and a tabloid journalist for a wife has the Prime Minister on his toes, and by association Claude Whelan the new head of the Secret Service. Whelan will soon have more trouble to deal with, including a Muslim MP who is acting strangely and his own service being implicated in the attack. Slough House, the dumping ground for washed up spies, is never far from the Secret Services woes and one its occupants soon find themselves the target of a murder and the team chasing terrorists despite them supposedly being locked-down. Slough House might be home to the slow horses - capable of making any situation worse - but they still play with London Rules.London Rules is the fifth book in the excellent Slow Horses series about the exploits of a bunch of has-been spies, each with a personal problem, who’ve been sent to Slough House to see out the rest of their career. In this outing, the gang of misfits are trying to get to the bottom of why Roddy Ho, a narcissist hacker with a personality bypass, is the target of a murder attempt and tangling with a terrorist cell enacting an old British secret service plan designed to destabilise a country. As usual, they are only partially equipped to deal with the threat and quickly make matters worse by accidentally killing a person they’re trying to protect. What makes the book shine are Herron’s cast of dysfunctional characters and their interactions that mix farce, slapstick and politically incorrectness. The dialogue often sparkles, especially any conversation involving Jackson Lamb, a man who treats everyone with disdain and condescension; a man who thrives mansplaining mansplaining and is comfortable telling cripple jokes to a disabled woman. The plot thread involving the terrorists would have worked better I felt if they weren’t more incompetent than the slow horses: the only thing that kept them from being caught quickly was luck, momentum and picking non-obvious targets. In a way the plot almost felt like a foil designed to enable Herron to spin some farce and create character situations, and poke fun at politics and the establishment, rather than being the central concern. Nonetheless, another clever, witty addition to a must-read series that is crying out for adaptation for television.

Published on June 11, 2019 01:30

June 9, 2019

Lazy Sunday Service

Yesterday was publication day for 'The Right to the Smart City' book edited by Paolo Cardullo, Cesare Di Feliciantonio and myself published by Emerald. The book focuses on the interrelationship of smart cities, rights, citizenship, social justice, commons, civic tech, participation and ethics, and includes chapters by Katharine Willis, Jiska Engelbert, Alberto Vanolo, Michiel de Lange, Catherine D'Ignazio, Eric Gordon, Elizabeth Christoforetti, Andrew Schrock, Sung-Yueh Perng, Gabriele Schliwa, Nancy Odendaal, Ramon Ribera-Fumaz, and the three editors.

Yesterday was publication day for 'The Right to the Smart City' book edited by Paolo Cardullo, Cesare Di Feliciantonio and myself published by Emerald. The book focuses on the interrelationship of smart cities, rights, citizenship, social justice, commons, civic tech, participation and ethics, and includes chapters by Katharine Willis, Jiska Engelbert, Alberto Vanolo, Michiel de Lange, Catherine D'Ignazio, Eric Gordon, Elizabeth Christoforetti, Andrew Schrock, Sung-Yueh Perng, Gabriele Schliwa, Nancy Odendaal, Ramon Ribera-Fumaz, and the three editors.My posts this week

Review of The Shape of the Ruins by Juan Gabriel Vasquez

Generally being the operative word

May reviews

Published on June 09, 2019 03:52

June 8, 2019

Generally being the operative word

McStay’s gaze settled on the hands clutching the crucifix.

‘Copycat killing,’ Logan said. ‘Poor cow.’

‘Unless Tasker is innocent.’

‘Tasker killed those three women. A court convicted him.’

‘So? Judge and juries get it wrong. We get it wrong.’

‘Don’t let Carmichael hear you say that.’

‘Carmichael’s a great believer in Occam’s Razor.’

‘Meaning?’

‘He likes easy solutions.’

‘Because they’re generally right.’

‘Generally being the operative word. Tasker has always protested his innocence. Never confessed. Didn’t even hint at it.’

‘You really think this is the same killer?’

‘Or it could be a copycat.’

‘Jesus, Gerry, make your mind up!’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

‘Copycat killing,’ Logan said. ‘Poor cow.’

‘Unless Tasker is innocent.’

‘Tasker killed those three women. A court convicted him.’

‘So? Judge and juries get it wrong. We get it wrong.’

‘Don’t let Carmichael hear you say that.’

‘Carmichael’s a great believer in Occam’s Razor.’

‘Meaning?’

‘He likes easy solutions.’

‘Because they’re generally right.’

‘Generally being the operative word. Tasker has always protested his innocence. Never confessed. Didn’t even hint at it.’

‘You really think this is the same killer?’

‘Or it could be a copycat.’

‘Jesus, Gerry, make your mind up!’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

Published on June 08, 2019 03:53

June 5, 2019

Review of The Shape of the Ruins by Juan Gabriel Vasquez (2018, Riverhead Books)

At a party the author is introduced to Carlos Carballo, a man obsessed with political assassinations. He wants Vasquez to write a book about the assassination of the Colombian liberal, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, murdered by a lone gunman on the 9th April 1948, plunging the country into a ten year civil war in which an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 people died and a million were displaced. Like the rumours surrounding the murder of General Rafael Uribe Uribe in 1914, and the assassination of John Kennedy, Carballo is convinced that there was a wider conspiracy behind Gaitán’s death involving at least one other gunman backed by a group hiding in the shadows manipulating events. Vasquez gets into an argument with Carballo, accidentally breaking his nose in the altercation. A few years later Vasquez meets Carballo again, giving away information that would be of interest for his conspiracy theory, which leads to a theft. Vasquez promises to try and recover the object by promising to write the book Carballo wants written. The material Carballo produces captures Vasquez’s imagination making him question accepted history despite him being resistant to revisionist claims.

At a party the author is introduced to Carlos Carballo, a man obsessed with political assassinations. He wants Vasquez to write a book about the assassination of the Colombian liberal, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, murdered by a lone gunman on the 9th April 1948, plunging the country into a ten year civil war in which an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 people died and a million were displaced. Like the rumours surrounding the murder of General Rafael Uribe Uribe in 1914, and the assassination of John Kennedy, Carballo is convinced that there was a wider conspiracy behind Gaitán’s death involving at least one other gunman backed by a group hiding in the shadows manipulating events. Vasquez gets into an argument with Carballo, accidentally breaking his nose in the altercation. A few years later Vasquez meets Carballo again, giving away information that would be of interest for his conspiracy theory, which leads to a theft. Vasquez promises to try and recover the object by promising to write the book Carballo wants written. The material Carballo produces captures Vasquez’s imagination making him question accepted history despite him being resistant to revisionist claims.The Shape of the Ruins is an auto-fiction account of how Vasquez comes to write a novel concerning the assassinations of two twentieth century Colombian politicians that had lasting consequences for the country. The first death is the murder of General Rafael Uribe Uribe in 1914 and the parallel inquiry conducted by a young lawyer, Marco Tulio Anzola, who published a book in 1917 setting out an alternative account to the official investigation. The second murder is the assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in 1948 and the obsessive investigation by Carlos Carballo who wants to produce a book that replicates Anzola’s work. Carballo has assembled what he believes is extensive evidence of a conspiracy concerning Gaitán’s death, but he wants a professional writer of Vasquez’s stature to write the book. Carballo meets Vasquez at a party, but Vasquez wants no part of the venture. Circumstances, however, conspire to make Vasquez take on the job. His investigation leads him to question the nature of history and conspiracy theories, and the obsessions of those that seek to challenge and re-write the past. It’s a fairly lengthy tale, with much philosophical wandering and autographical asides, and long passages recounting Anzola’s and Carballo’s stories. Given the mix of official history and conspiracy theories it’s difficult to know the extent to which the tale is fiction and faction, which matches in many ways the contested nature of Colombian history. And that’s the point of the story, I feel, given the politics and violence that haunts the country. In that sense, the book makes an engaging, reflexive and thoughtful intervention regarding Colombian identity, memory, and living with the past. It’s a little too long in places, especially recounting Anzola’s quest, but is nonetheless an interesting read.

Published on June 05, 2019 08:03

June 3, 2019

May reviews

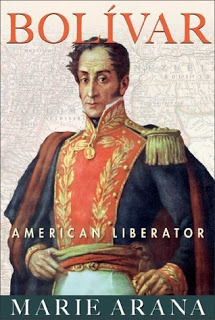

May was mostly a good month of reads. Bolivar was an excellent book, but my read of the month was Herman Wouk's The Caine Mutiny, who coincidentally died a couple of days after my review.

May was mostly a good month of reads. Bolivar was an excellent book, but my read of the month was Herman Wouk's The Caine Mutiny, who coincidentally died a couple of days after my review.Bolivar: American Liberator by Marie Arana *****

The Lightning Men by Thomas Mullen ****

The Secret Listeners by Sinclair McKay **.5

The Last Time We Spoke by Fiona Sussman ***.5

The Caine Mutiny by Herman Wouk *****

August Snow by Stephen Mack Jones ****

Detective Inspector Huss by Helene Tursten ****

The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre ****.5

Published on June 03, 2019 09:51

June 2, 2019

Lazy Sunday Service

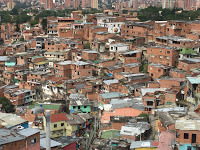

I spent last week in Medellin, Colombia taking part in a workshop and taking a look around the city. A vibrant, interesting place that's trying to put its troubled history behind it. The workshop was excellent and the city well worth a visit. I didn't spot a novel set in the city, so settled for Juan Gabriel Vásquez's The Shape of the Ruins set mainly in Bogota. I'll try and post a review during the week.

I spent last week in Medellin, Colombia taking part in a workshop and taking a look around the city. A vibrant, interesting place that's trying to put its troubled history behind it. The workshop was excellent and the city well worth a visit. I didn't spot a novel set in the city, so settled for Juan Gabriel Vásquez's The Shape of the Ruins set mainly in Bogota. I'll try and post a review during the week. My posts this week

Review of Bolivar: American Liberator by Marie Arana

Review of Bolivar: American Liberator by Marie AranaReview of The Lightning Men by Thomas Mullen

Holy cow

Published on June 02, 2019 12:51

June 1, 2019

Holy cow

‘I don’t think this is going to work, Wes.’

‘You’re breaking up with me?’

‘We’re chalk and cheese.’

‘You are breaking up with me. Holy cow.’

‘I mean, who says ‘holy cow’ anymore?’

‘You’re breaking up with me because I say holy cow?’

‘No. Yes. It’s symptomatic of what’s wrong.’

‘Wow. And I thought it was going swell. Shows how much of a dupe I am.’

‘I’m just saying that we aren’t suited. We like different things.’

‘Except each other.’

‘Wes.’

‘Not even each other? Wow. You’re some actress.’

‘That’s not fair.’

‘None of this seems fair, Diane. Holy cow.’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

‘You’re breaking up with me?’

‘We’re chalk and cheese.’

‘You are breaking up with me. Holy cow.’

‘I mean, who says ‘holy cow’ anymore?’

‘You’re breaking up with me because I say holy cow?’

‘No. Yes. It’s symptomatic of what’s wrong.’

‘Wow. And I thought it was going swell. Shows how much of a dupe I am.’

‘I’m just saying that we aren’t suited. We like different things.’

‘Except each other.’

‘Wes.’

‘Not even each other? Wow. You’re some actress.’

‘That’s not fair.’

‘None of this seems fair, Diane. Holy cow.’

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

Published on June 01, 2019 04:57

Review of Bolivar: American Liberator by Marie Arana (2013, Simon Schuster)

Simón Bolivar (1783-1830) is a figure surrounded by myths and legends. Loved and reviled in his lifetime, his character and achievements were subsequently invoked both positively and negatively by politicians of every hue. Bolivar freed much of Latin America from Spanish colonial rule through a series of battles and conquests, creating a united Greater Colombia founded on the principles of liberty, democracy, and the abolition of slavery and racial/class hierarchies. In subsequent years, in the aftermath of war and the collapse of existing political and administrative systems, this divided into six new nations: Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Bolivar, Ecuador and Panama. The campaigns he fought were extremely bloody affairs, accompanied by fragile alliances and fraught politics. Not only was he a great military leader, but also a canny statesman. Nonetheless, while recognized as an exceptional leader, he was ultimately rejected by each state and died destitute, alone except for a handful of loyal friends and family, as he waited for a ship to take him into exile.

Simón Bolivar (1783-1830) is a figure surrounded by myths and legends. Loved and reviled in his lifetime, his character and achievements were subsequently invoked both positively and negatively by politicians of every hue. Bolivar freed much of Latin America from Spanish colonial rule through a series of battles and conquests, creating a united Greater Colombia founded on the principles of liberty, democracy, and the abolition of slavery and racial/class hierarchies. In subsequent years, in the aftermath of war and the collapse of existing political and administrative systems, this divided into six new nations: Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Bolivar, Ecuador and Panama. The campaigns he fought were extremely bloody affairs, accompanied by fragile alliances and fraught politics. Not only was he a great military leader, but also a canny statesman. Nonetheless, while recognized as an exceptional leader, he was ultimately rejected by each state and died destitute, alone except for a handful of loyal friends and family, as he waited for a ship to take him into exile.Given his achievements and his many conflicts with foes and allies, it’s no wonder that he’s remembered in a variety of ways. Writing his biography in a relatively neutral way is no easy task. Marie Anana does an admirable job, however, of trying to chart his life, drawing extensively on historical sources, including surviving letters and testimony of various kinds. She’s careful to question dubious sources or note speculation when the historical record is missing. The story she tells is captivating, full of adventure, romance, conflict, and messy politics. Bolivar travelled 75,000 miles, mostly on horseback as he criss-crossed the northern part of South America, as well as sailed its coast, canoed its rivers, and journeyed around Europe. His wife died shortly after marriage and he subsequently had several affairs, often simultaneously. He built many alliances with men and armies that swapped sides several times and were quite happy to undermine his authority. He drafted constitutions, laws, and decrees, and founded parliaments. He understood that a democracy could not have a dictator, yet he craved and also rejected power. He lived a full, eventful and consequential life and his achievements are still having consequence. Anana’s narrative is highly readable, told with engaging voice. She covers his full life story, balancing detail with brevity, keeping the pace relatively swift. It’s still a fairly large tome, but to do justice to the life lived it cannot be any other way. The result is a lively, well-told biography.

Published on June 01, 2019 01:30