Rob Kitchin's Blog, page 169

September 19, 2013

Review of All the Lonely People by Martin Edwards (1991, Arcturus Classic Crime)

Harry Devlin is a duty solicitor in central Liverpool. Since his wife, Liz, left him he leads a solitary life, his time revolving around work and representing petty criminals during interviews and in court. It’s definitely not the glamorous side of legal work and nor does it pay handsomely. Arriving home late at night he finds his former wife waiting in his apartment. Always the life and soul of a party, she’d left him for a well connected criminal. Harry has never stopped loving her and when she asks if she can stay for a few days whilst she sorts out her personal life he agrees against his better judgement. Within twenty four hours she is dead, stabbed to death in an alley. Rather than leave the case to the police, Harry decides he’s going to catch his ex-wife’s killer. He starts to follow up on leads, but it’s clear that neither the police nor the perpetrator are happy with his crusade. Regardless, he persists with his investigation, whilst at the same time fending off the advances of his lonely neighbour.

Harry Devlin is a duty solicitor in central Liverpool. Since his wife, Liz, left him he leads a solitary life, his time revolving around work and representing petty criminals during interviews and in court. It’s definitely not the glamorous side of legal work and nor does it pay handsomely. Arriving home late at night he finds his former wife waiting in his apartment. Always the life and soul of a party, she’d left him for a well connected criminal. Harry has never stopped loving her and when she asks if she can stay for a few days whilst she sorts out her personal life he agrees against his better judgement. Within twenty four hours she is dead, stabbed to death in an alley. Rather than leave the case to the police, Harry decides he’s going to catch his ex-wife’s killer. He starts to follow up on leads, but it’s clear that neither the police nor the perpetrator are happy with his crusade. Regardless, he persists with his investigation, whilst at the same time fending off the advances of his lonely neighbour.All the Lonely People was Martin Edwards debut novel and the first book in an eight part series featuring world weary but tenacious solicitor, Harry Devlin. The story has the feel of a classical who-dunnit, with Devlin taking on the role of a put-upon, down at heel PI, and the tale focusing on the characters, their relationships, and the investigation, but with little gore or unrealistic or heightened tension. Edwards does a nice job of contextualising Harry’s life as a duty solicitor, evoking Liverpool at the end of the 1980s, and capturing the lives of the poorest strata of society and their social relations. The characterisation is nicely observed, as is the interplay between the characters. For the most part the story works well, but the puzzle seemed a bit too weak and the killer well signposted, in part because the misdirection was a little too obvious. Nonetheless, I found it an entertaining read and hope to spend some more time in Harry’s company in the future.

Published on September 19, 2013 02:53

September 16, 2013

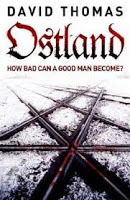

Review of Ostland by David Thomas (Quercus, 2013)

Georg Heuser is an ambitious police officer who has come top of his graduating class. His reward is to be placed as an apprentice to Wilhelm Ludtke, head of the Berlin murder squad. He joins the squad in February 1941 in the middle of one of the highest profile criminal cases of the war – the S-Bahn murders, where a man is raping and murdering young women on and near to the Berlin train system. The squad are under enormous pressure from their boss, General Heydrich, to bring the killer to justice, yet he’s proving highly elusive. Heuser is determined to prove his worth, both in terms of work and politically, with the aim of being noticed and securing rapid promotion. This he achieves and once the case is closed he is transferred east to Minsk to help oversee the policing in the newly conquered territory and the administering of the final solution to local Jews and those being transferred to the area. Despite his revulsion at his orders, he proceeds to carry out them out, eventually becoming head of the Minsk Gestapo. As the Russians approach he heads west and survives the war, rejoining the police and rising to become chief of police in Rhineland-Pfalz. In 1959 he’s arrested, accused of war crimes and eventually put on trial. Ostland tells his story and that of the case against him.

Georg Heuser is an ambitious police officer who has come top of his graduating class. His reward is to be placed as an apprentice to Wilhelm Ludtke, head of the Berlin murder squad. He joins the squad in February 1941 in the middle of one of the highest profile criminal cases of the war – the S-Bahn murders, where a man is raping and murdering young women on and near to the Berlin train system. The squad are under enormous pressure from their boss, General Heydrich, to bring the killer to justice, yet he’s proving highly elusive. Heuser is determined to prove his worth, both in terms of work and politically, with the aim of being noticed and securing rapid promotion. This he achieves and once the case is closed he is transferred east to Minsk to help oversee the policing in the newly conquered territory and the administering of the final solution to local Jews and those being transferred to the area. Despite his revulsion at his orders, he proceeds to carry out them out, eventually becoming head of the Minsk Gestapo. As the Russians approach he heads west and survives the war, rejoining the police and rising to become chief of police in Rhineland-Pfalz. In 1959 he’s arrested, accused of war crimes and eventually put on trial. Ostland tells his story and that of the case against him.Ostland is a fictionalised account of parts of the career of ‘Dr’ Georg Heuser – his part in solving the famous S-Bahn murders and his role in the murders of thousands of Jews and others in occupied Russia a few months later, and his arrest fourteen years after the end of the war and subsequent trial. The first elements are told in the first person from Heuser’s perspective, the latter in the third person from the perspective of two prosecuting, investigative lawyers, Paula Siebert and Max Kraus. Whilst Heuser and his colleagues are real people, Siebert and Kraus are fictional. Both parts of the story are based on documentary evidence presented in Heuser’s trial, along with other research by Thomas. I’m always a little wary of fictionalised version of real events as the danger is the creation of revisionist history that distorts what really occurred – my sense is why not just write a factual history book, especially since we have no idea of the inner thoughts of particular characters. In Ostland, however, the fictional form works remarkably well, in the main because Thomas uses the form to explore wider questions of moral philosophy: what compels men to commit truly evil acts and how should such men be judged?

Heuser’s case is interesting basis on which to explore such questions as he went from investigating what was considered one of the most evil killers in the Reich, to be a state-sanctioned murderer. Thomas unsettles the reader by portraying Heuser through an everyday lens and as being cultured, reflexive, obedient and ambitious, and not as a psychopathic monster, as well by detailing the logic of how the law works and a general desire at the time of the trial to forget the past and move-on. It is a story that becomes more compelling and disturbing as it progresses, especially as cracks and doubts are added to Heuser’s professional demeanour and the account unsettles what would seem like commonsensical judgements about Heuser’s actions. There’s no doubt that the story is distressing in its telling of both the S-Bahn murders and the genocide in Minsk, and it’s not a tale for the faint-hearted. But for those prepared to make their way to the end it’s a thought-provoking read, especially when one starts to consider what they would have done in the same situations and context, and how one would subsequently try to rationalise actions and live with oneself. In this sense, whilst the story is quite simply told, it packs a very powerful punch that is likely to stay with the reader for quite some time.

Published on September 16, 2013 01:12

September 15, 2013

Lazy Sunday Service

After two weeks travelling by train with my

After two weeks travelling by train with my

father round the Czech Republic and Eastern Germany I am feeling cultured out. I don't think I've ever been to so many museums and heritage attractions in such a short space of time before. Other than general wandering around, here's where we visited, all of which were interesting places and worth checking out. The picture is the rebuilt skyline of Dresden. I'm just finishing a book about the bombing raids that flattened the city in February 1945. The skyline once again resembles that painted by Canaletto in 1748, when it was known as 'Florence on the Elbe'.

father round the Czech Republic and Eastern Germany I am feeling cultured out. I don't think I've ever been to so many museums and heritage attractions in such a short space of time before. Other than general wandering around, here's where we visited, all of which were interesting places and worth checking out. The picture is the rebuilt skyline of Dresden. I'm just finishing a book about the bombing raids that flattened the city in February 1945. The skyline once again resembles that painted by Canaletto in 1748, when it was known as 'Florence on the Elbe'.Prague

Prague Castle, including St. Vitus Cathedral, The Story of Prague Castle, St. George's Basilica, Prague Castle Picture Gallery, Powder Tower.

Museum of Communism

The Army Museum Žižkov

Dresden

Albertinium

Zwinger – Old Masters Picture Gallery, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments

Royal Palace - New Green Vault, Armoury, Turkish Chamber

VW Transparent Factory

Leipzig

Museum of City History

Museum in the ‘Rounded Corner’ (Stasi Museum)

Museum of the Printing Arts

Museum of Fine Arts

Wernigerode

HSB Steam train up Brocken Mountain

Berlin

Topography of Terror and Checkpoint Charlie

Schloss Charlottenburg

Jewish Museum Berlin

Museum of Technology

My posts this week

Review of Tretjak by Max Landorff

Review of The Darkling Spy by Edward Wilson

Next batch of reads

Review of The Good German by Joseph Kanon

A deadly descent?

Published on September 15, 2013 04:23

September 14, 2013

A deadly descent?

Dieter stared out the window of the train at the tall pines and rocky outcrops. Suddenly the sound of the struggling engine was punctuated by a loud explosion and violent juddering. Jolted to the floor, it took a moment before the shouts, screams and rattle of machine guns registered. Two round holes pierced the wooden slat above his head and he snapped back into reality. Clambering to his knees he felt the floor sway as the carriage started to roll backwards. As the remains of the train began its descent, slowly picking up speed, he fired blindly into the trees.

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words.

Published on September 14, 2013 01:30

September 13, 2013

Review of The Good German by Joseph Kanon (2001, Sphere)

Jake Geismar worked as a reporter in Berlin up until the autumn of 1941. He then worked in North Africa and Italy before working his way into Germany with General Patton’s army, visiting a couple of death camps. Before leaving Germany he vowed to Lena, a work colleague with whom he was having an affair, that he would return after the war so they could resume their relationship. But flying into the shattered ruins of Berlin to cover the meeting of Churchill, Truman and Stalin, and to report on the city, its inhabitants and political division and administration for Collier’s Magazine, he’s worried that she hasn’t survived the war. He soon has other stories to keep him occupied – a US soldier that shared his flight is found murdered with a stash of money, a congressman keen to snap up German scientists for the US, the uncovering of Nazi war criminals who are seeking to make their past disappear, and allied soldiers on the make in a thriving black market. Geismar is determined to find Lena and get to the bottom of each of these issues, particular the death of the US soldier, but the more he digs, the more complicated and interwoven the stories become and the more danger he finds himself in.

Jake Geismar worked as a reporter in Berlin up until the autumn of 1941. He then worked in North Africa and Italy before working his way into Germany with General Patton’s army, visiting a couple of death camps. Before leaving Germany he vowed to Lena, a work colleague with whom he was having an affair, that he would return after the war so they could resume their relationship. But flying into the shattered ruins of Berlin to cover the meeting of Churchill, Truman and Stalin, and to report on the city, its inhabitants and political division and administration for Collier’s Magazine, he’s worried that she hasn’t survived the war. He soon has other stories to keep him occupied – a US soldier that shared his flight is found murdered with a stash of money, a congressman keen to snap up German scientists for the US, the uncovering of Nazi war criminals who are seeking to make their past disappear, and allied soldiers on the make in a thriving black market. Geismar is determined to find Lena and get to the bottom of each of these issues, particular the death of the US soldier, but the more he digs, the more complicated and interwoven the stories become and the more danger he finds himself in. The Good German has the feel of a Hollywood movie, blending a romance story with that of a thriller, accompanied by strong undercurrents of justice and morality during and after war – he’s a US reporter and she’s the German wife of a rocket scientist who’ve been separated by the conflict; he’s now searching for her at the same time as pursuing the biggest story of his career, one that puts them both in great danger. It’s a tale that seeks to be a mainstream romantic thriller, whilst also covering big themes such as war crimes and the Allies conflicting positions on how to deal with Germany and its people in the immediate aftermath of the war and the tensions and manoeuvring between them. Kanon manages to skilfully mix the style and substance, providing two long intersecting story arcs focused on Jake and Lena’s romance and the murder mystery with respect to the death of a US soldier, whilst also delivering a number of interesting subplots. The characterisation, historical contextualisation and sense of place and time are very good throughout. The writing and plotting is assured and engaging, though sometimes is a little longwinded and melodramatic, and the interconnection of all subplots is overly convenient and contrived. Nonetheless, The Good German is a compelling, atmospheric page-turner and thought-provoking read.

Published on September 13, 2013 01:52

September 12, 2013

Next batch of reads

This is my first day back at work after three weeks holiday. That's the longest break I've had in well over a decade. On my return I found three new books waiting for me: Laura Wilson's The Riot, Barbara Nadel's A Private Business, and Geoffrey McGeachin's Black Wattle Creek. Along with Arnaldur Indridason's Strange Shores my plan is to make them my next quartet of reads, so expect reviews to start appearing in a couple of weeks.

This is my first day back at work after three weeks holiday. That's the longest break I've had in well over a decade. On my return I found three new books waiting for me: Laura Wilson's The Riot, Barbara Nadel's A Private Business, and Geoffrey McGeachin's Black Wattle Creek. Along with Arnaldur Indridason's Strange Shores my plan is to make them my next quartet of reads, so expect reviews to start appearing in a couple of weeks.

Published on September 12, 2013 02:23

September 11, 2013

Review of The Darkling Spy by Edward Wilson (Arcadia Books, 2010)

1956 and the cold war is heating up. The reputation of Britain’s intelligence services lies in tatters after the defection of Burgess and Maclean, with the suspicion of other traitorous spies still in place. Henry Bone, a British spymaster, has discovered that a key East European spy, codenamed Butterfly, is about to defect to the Americans. Butterfly has plagued Bone for two decades and carries secrets that would further damage Britain’s reputation. To try and get to Butterfly first Bone turns to his protégé, William Catesby. Catesby is already perceived by some to be a security risk given his Belgium mother, working class background and socialist sympathies. After a mission to Budapest at the height of the uprising in 1956 and a personal scandal, Catesby is persuaded to be a plant defector to East Germany, hoping to identify Butterfly before he defects himself. It’s a mission that places duty ahead of all else and Catesby’s hoping that he hasn’t made a fatal choice.

1956 and the cold war is heating up. The reputation of Britain’s intelligence services lies in tatters after the defection of Burgess and Maclean, with the suspicion of other traitorous spies still in place. Henry Bone, a British spymaster, has discovered that a key East European spy, codenamed Butterfly, is about to defect to the Americans. Butterfly has plagued Bone for two decades and carries secrets that would further damage Britain’s reputation. To try and get to Butterfly first Bone turns to his protégé, William Catesby. Catesby is already perceived by some to be a security risk given his Belgium mother, working class background and socialist sympathies. After a mission to Budapest at the height of the uprising in 1956 and a personal scandal, Catesby is persuaded to be a plant defector to East Germany, hoping to identify Butterfly before he defects himself. It’s a mission that places duty ahead of all else and Catesby’s hoping that he hasn’t made a fatal choice.The Darkling Spy is a cold war spy story in the mould of John Le Carre – a dark, complex, layered tale of small heroic, compromising and treacherous acts and mind games, rather than the action, thrills and womanising of Fleming. Wilson creates a world in which no-one quite trusts anyone else, even family, friends and allies; in which the wrong decisions can have fatal consequences. It is a world of pervaded by lies, deception, mis- and dis-information, politics and ideology. There is a strong sense of atmospherics and sense of place throughout and the story is told through an engaging voice. Bone and Catesby are convincing characters with interesting back stories that are nicely portrayed and the other characters are well penned. The plotting is very nicely done, with the various pieces of the jigsaw manoeuvred into place and the final picture only being revealed in the last few pages. The denouement felt a little flat, although in keeping with the understated telling of the rest of the story. Overall, a very good cold war spy tale.

Published on September 11, 2013 01:30

September 9, 2013

Review of Tretjak by Max Landorff (Haus Publishing, 2011 German, 2013 English)

Gabriel Tretjak lives his life in relation to a strict code designed to keep everything under perfect, ordered control. The code minimizes complications and makes him very successful at what he does, which is to fix the problems in other peoples’ lives. For a substantial fee he creates and executes solutions, rebuilding the personal and professional lives of his clients, whatever the situation or scandal. In the past, Tretjak used the code to fix his own life after a troubled upbringing, and it seems as if he needs to do so again as someone undertakes a series of murders that all suggest he is the perpetrator. The calm and clever Inspector Maler certainly believes so as he investigates the grizzly crimes. Tretjak knows he is innocent, but someone seems to have out-fixed the fixer. In order to counter the compelling evidence and stay out of jail he’s going to need one heck of a solution.

Gabriel Tretjak lives his life in relation to a strict code designed to keep everything under perfect, ordered control. The code minimizes complications and makes him very successful at what he does, which is to fix the problems in other peoples’ lives. For a substantial fee he creates and executes solutions, rebuilding the personal and professional lives of his clients, whatever the situation or scandal. In the past, Tretjak used the code to fix his own life after a troubled upbringing, and it seems as if he needs to do so again as someone undertakes a series of murders that all suggest he is the perpetrator. The calm and clever Inspector Maler certainly believes so as he investigates the grizzly crimes. Tretjak knows he is innocent, but someone seems to have out-fixed the fixer. In order to counter the compelling evidence and stay out of jail he’s going to need one heck of a solution.There’re relatively few untapped angles to the crime genre, with most stories falling into a set of established sub-genres and tropes. Tretjak works ‘the fixer’ angle, but does so with a nice philosophical undertone that gives it freshness. Tretjak is not the most likeable of characters, but Landorff does a good job of setting out his back story and exploring his various traits and neuroses over the course of the book as he reacts to the attempt to frame him for murder and the intervention of his estranged father. The other principle characters also have depth and are nicely developed. The plot for the most part works well, being layered and complex, with the philosophical elements providing some nice reflective moments. However, there were a couple of dangling threads that were left unexplained and the resolution felt somewhat contrived, a little clunky, and was telegraphed from quite a way out. The result was a slightly flat ending to a mostly thoughtful read. Overall, an interesting, literary crime fiction story.

Published on September 09, 2013 01:00

September 8, 2013

Lazy Sunday Service

I'm on a run of historical crime fiction set in the 1940s/50s at the moment. In addition to Echoland and Stettin Station, I've recently read The Darkling Spy by Edward Wilson and The Good German by Joseph Kanon (reviews in the next few days). And I've just started Ostland by David Thomas. After that I think it'll be time to reorient back to the present and away from Germany for a couple of books.

I'm on a run of historical crime fiction set in the 1940s/50s at the moment. In addition to Echoland and Stettin Station, I've recently read The Darkling Spy by Edward Wilson and The Good German by Joseph Kanon (reviews in the next few days). And I've just started Ostland by David Thomas. After that I think it'll be time to reorient back to the present and away from Germany for a couple of books.Review of Stettin Station by David Downing

Review of Echoland by Joe Joyce

August reviews

Review of Love Songs from a Shallow Grave by Colin Cotterill

Published on September 08, 2013 01:30

September 7, 2013

An ambush in the mountains

Muddy brown smoke bloomed out of the trees as the train struggled up the incline.

Tomas watched its progress through a pair of binoculars.

‘Remember, Peter, not too early.’

‘Maybe you should do it?’

‘Just as we planned, okay.’ He signalled to a comrade to their left.

The engine turned into view, growling and hissing. As it neared, tired faces appeared in the filthy windows.

Pasha watched the front wheels reach the marker.

The explosion lifted the engine from the track and down the slope, pulling two carriages with it. Then the rattle of machine guns, shouted orders, and screams.

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words

Tomas watched its progress through a pair of binoculars.

‘Remember, Peter, not too early.’

‘Maybe you should do it?’

‘Just as we planned, okay.’ He signalled to a comrade to their left.

The engine turned into view, growling and hissing. As it neared, tired faces appeared in the filthy windows.

Pasha watched the front wheels reach the marker.

The explosion lifted the engine from the track and down the slope, pulling two carriages with it. Then the rattle of machine guns, shouted orders, and screams.

A drabble is a story of exactly 100 words

Published on September 07, 2013 01:30