Darcy Pattison's Blog, page 9

April 4, 2016

From Novel to Movie: Greenhorn by Anna Olswanger

at Highlights Foundation

Picture Books and All That Jazz - How to Write a Picture Book

Master Class in Novel Writing

Anna Olswanger’s middle grade novel, GREENHORN (See Review), was made into an indie film. It’s a dream that many of us have, to see our story on the big screen. I asked her to tell us about the process.

Anna Olswanger’s middle grade novel, GREENHORN (See Review), was made into an indie film. It’s a dream that many of us have, to see our story on the big screen. I asked her to tell us about the process.

Anna’s introduction to the story

In 2014 I co-produced a short indie film adaptation of the novel. The film premiered at the Landmark NuArt Theatre in L.A. and at The Museum of Tolerance in New York. It was named the 2015 Audience Award Winner for Best Short Film Drama at the Morris and Mollye Fogelman International Jewish Film Festival in Memphis, and subsequently aired on public television in Memphis and Kentucky. In February, 2016, it was part of the Festival Internacional De Cine Judio en Mexico and will screen on March 27, 2016 at the International Children’s Film Festival at L.A.’s WonderCon.

TMW Media has just started distributing the film so that libraries and schools can purchase the DVD with public performance rights and show the film in classrooms. TMW is also distributing the film on Amazon to individual viewers. The film could be a tie-in to Holocaust Remembrance Day in May and International Holocaust Remembrance Day in January. The discussion guide for the film is online at the distributor’s site:

When did you decide that this book would make a good film?

I think every author hopes that her book will be optioned for film, and as a literary agent, I am used to getting my clients’ books into the hands of film producers. In the case of Greenhorn, I thought that the story had conflict, a strong climax, and a poignant resolution, the right elements for a good film. I just didn’t know how I would interest a producer in such a short book.

How did you find the contact to adapt it to film?

A potential client, who is a screenwriter, submitted a children’s book manuscript to me. It wasn’t a manuscript I could successfully represent, but we began a conversation about her work and she suggested that I show Greenhorn to a director she had worked with. I did contact him, and he liked the book. He asked me if I would like to co-produce the film with him.

As the author, what involvement did you have in the script? Did you have rights of approval/disapproval?

Because I was the co-producer, I was able to read the script and comment on it. My main concern was authenticity. I wanted to make sure that anyone familiar with that era of history during the 1940s would be convinced by the film.

Once the book goes to film, who is in charge? Where does the buck stop? When the book is adapted for film what is the author’s role? Nothing? Or do you have veto rights on decisions? For example, Ella Enchanted became a farce almost in movie format, a far cry from the book itself. Authors worry. What if their “baby” is misunderstood?

As a literary agent, I can confirm that the interpretation of the producer and screenwriter is of concern to authors. But unless you’re a big name author, you have to let go of your book when you option it. You’ve been paid money by someone who is excited by your story and has a vision of it as a film, and you have to trust that this person’s vision will enhance your book. If you don’t trust the producer, then don’t option the book. I think the situation is similar to being the author of a picture book text and having to let go when the illustrator comes on board. The picture book author has to let the illustrator have her own vision of the story. You can’t control what the illustrator sees. However, I was in the unique position of being both the author of the book and the co-producer of the film, so I was able to read the script and make suggestions for changes.

As the author, what surprised you about the film adaptation?

I remember from my days as a college theatre major how quickly and deeply friendships are formed among cast members, but it surprised me to see similar friendships develop among the boys who were in the cast of this film. It was fun to watch them play around during the times when we weren’t filming. See the wonderful photo of them after we filmed a scene.

The director/screenwriter, who happens not to be Jewish, recently told me he wants to develop a feature-length version of the story to flesh out the backstory of the children and their lives outside the yeshiva. It constantly surprises me how this story resonates with people, especially people who have no connection to the Holocaust or even Jewish history.

Will the process change how you write your next book?

I don’t think so, but the process has made me see how satisfying it is to see work in one medium take on a life in another medium.

Is there any money in all of this for you, the author?

Greenhorn is a small indie film, and as the co-producer I had to raise the funds to pay the actors, the production staff, the travel and hotel expenses for the crew during filming, props, hair dresser, catering, music, post sound design, and insurance. We didn’t budget in fees for the director or producers, or for me as the author, so there isn’t money in this for me. Even so, I would do it again.

Trailer for Greenhorn

If you can’t see this video, click here.

Darcy’s note about developing your own PR package:

For publicity purposes, Anna presented me with a complete package. She quickly answered some key questions about the process of creating a film from a novel. When she sent me the answers, she included interesting photos, details about where the film had aired, how to buy the movie on Amazon, links to a free discussion guide, suggestions on when it might be appropriate to view the film in an education setting, and a great movie trailer easily available on YouTube. If you’re doing publicity for a book or movie, this is a case study in how to do it right!

The post From Novel to Movie: Greenhorn by Anna Olswanger appeared first on Fiction Notes.

March 28, 2016

Scrivener: Sculpting a Story

at Highlights Foundation

Picture Books and All That Jazz - How to Write a Picture Book

Master Class in Novel Writing

Do you write your novels? Or do you sculpt it out of words?

I’ve been working with Scrivener for about two years now, and on my current WIP, it’s finally starting to feel normal. In fact, it’s changed the way I work.

Before Scrivener

My working method in the before Scrivener days was a mixture of outlining and pantster. I outlined the story, wrote about half of it, stopped to re-outline and then wrote some more. Sometimes, I had to re-outline several times before I made it through a full draft.

After Scrivener

For a while, the same process carried on. But my current WIP has been different.

Scrivener is a complicated, multi-faceted program. It’s such a different program from writing in a word processor like MSWord, and so complex, that when I bought the program, I immediately took an online class with Gwen Hernandez (NOT an affiliate link, just a satisfied customer!). She takes you through the many elements that are possible when you use Scrivener.

One of the best things that Gwen said to me was to keep an open mind about how to use the program. She said don’t decide how to use some element of Scrivener. Instead, just work. As you’re working, when you need something – THEN decide how to accomplish what you want, using one of the available options.

The program has so many possibilities, for example, on how to mark up a file so you can find it later: file name, synopsis or summary of the contents, color-coding, notes and so on. You can look at it as if the chapter were file cards, or look at each discrete file, or look at them as a continuous text. What makes sense to one person would confuse another.

It reminds me of my daughter in Algebra class in high school. Her teacher required the dreaded notebook check. My daughter was required to keep every piece of paper given as notes or homework and organize them interleaved in a daily fashion. However, to her, it made more sense to keep the notes in one section by date, and the homework in another section by date. When she turned in her notebook–even though she had every single piece of paper required and organized in a logical way–she was given a zero. She refused the opportunity to reorganize it because, to her, it didn’t make sense.

That’s the beauty of Scrivener. You can organize it YOUR WAY!

How Scrivener is Changing My Writing Process

The biggest change is working in the Scrivener Binder. This time, it feels like I’m sculpting a story. Using the binder, I created 4 acts and set up files with names of what I expected to happen. Using either the Hero’s Journey or Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat outline method–sometimes a combination of both–I knew that at a certain point in the story, the main character had to face the villain. In another place, he could relax a bit and enjoy the new world into which he’d traveled. And so on.

That means the binder was a sort of loose outline for what should happen in a well-plotted story.

For a couple chapters (or maybe they’ll be scenes and be combined into a chapter–everything is loose right now), I wrote. But then, I started working all over the binder. I’d write a scrap of dialogue in one place, then jump down to another section and write a reaction to that dialogue. Exciting descriptions were added in appropriate places, then revised to fit the action that was added later.

Without Scrivener’s Binder, I’d be totally lost! With it, I’m able to walk around the story and look at its shape. It feels rather like a sculptor who takes a wire frame and adds clay to rough out a figure. Then, the sculptor refines a bit on the hands, skips to shape of the head, and approximates the way the clothing drapes the body. All the while, I”m walking all around the story, looking at it from different angles and seeing where things connect. Taking off bits here and adding bits there.

For example, an important plot point at one spot was that a supporting character was sick because of anemia. There was an Ah-Ha! moment when I realized that the anemia would get worse. In fact, it could get so bad that she’d need a blood transfusion. Who would be available for that? Since the main character is an alien, he couldn’t donate blood! Her estranged mother, of course, would be the poignant choice. But it had to all happen in the midst of a hand-to-hand combat. Can you see the scene? The doctor–under less than ideal conditions–is trying to put a needle in the mother’s arm to collect blood and as soon as there’s a full bag, well–you know that in fiction, everything has to get WORSE for the main character, right–so the fight gets too close and the bag of blood is split open and they have to start over again. Because the girl is so sick that she needs the blood NOW, or else.

That connection was amazing. The choice of anemia as the illness was a spur of the moment choice, in the midst of trying out some ideas about illnesses. Then, when the anemia needed to worsen (or she needed a different symptom of the illness), it made sense to take it to the extreme and to plop it down in the midst of an action scene to make it more urgent. The estranged mother made it more poignant.

Ah, but where did the estranged mother come from. In other words, I had to track her throughline in the story and account for her movements in every scene. Or else her presence in this crucial scene would feel wrong. How could she contribute to the ongoing scenes I had planned. Obviously, she’s a supporting character and not the main character. When and how would her presence make the story stronger? The question sent me skipping around the scenes in the Scrivener binder again.

The point is that this process is leading me to see things afresh and find unexpected options, which make perfect sense in the context of the story. Had I been writing chronologically, the connection may or may not have happened. I think not.

This method of working is fascinating.

It’s been hard to give myself permission to skip around like this. I’m really enjoying writing this story and hopefully, one day, you’ll enjoy reading it.

The post Scrivener: Sculpting a Story appeared first on Fiction Notes.

March 21, 2016

Rough Out a Scene: Goals, DOs, DON’Ts, and the Writing

at Highlights Foundation

Picture Books and All That Jazz - How to Write a Picture Book

Master Class in Novel Writing

Lately, I’ve taken to roughing out a scene before I start writing.

Rough Out a Scene: Goals

I want to be excited to write the scene. I’m looking for the sparks, the exciting bits of this particular scene. Finding this early is helpful because I don’t waste time slogging through extraneous stuff. Instead, I can decide on smart scene cuts so I stay interested, which means the audience will stay interested!

I want the scene setting and action beats to be roughed out. Beats are the small units of action of a story: he stopped, rubbed his nose, sneezed, grabbed a tissue, and then wheezed out an answer. They are intimately tied to the setting because the action moves in, out and through the scenery. In the theater, this would be blocking out a scene and deciding where the actor stands on the stage and how they move across the stage. I may also work on deciding when to zoom, pan or scan.

I want to know the characters’ emotional responses. When an action beat occurs, I want to know the responses of the characters. Why was it important to write this action beat? If it doesn’t evoke an emotional response, maybe it’s not important enough to include in the final draft.

Rough out a scene: Don’ts

I don’t worry about perfection. I give myself permission to produce what kids call “sloppy copy.” It’s OK. I just want something on the page so that it’s easier to get the scene right later.

Don’t worry about verb tense, present or past. Sometimes, I bounce around like crazy. It’s OK. I’ll fix it when I actually write the scene.

Don’t worry about POV. It’s OK. I’ll often change POV during this rough-in stage. One advantage of this is that I’ll know the character’s emotion response. If it’s the POV character, I may be able to use the info as their thoughts. If it’s not the POV character, I’ll have to change the response into a physical action or perhaps signal it with body language. In the roughing out stage, I just need to know the emotions. I’ll follow conventions later.

Don’t worry about punctuation. It’s OK. I don’t worry about quotation marks around speech, or any other punctuation marks at this stage.

Don’t worry about details (unless you can’t stand not to!). In my current WIP novel, for example, my characters are at the bottom of the North Sea and should be seeing several species of fish. What fish would they see? Sometimes, I can just put in a placeholider, such as XXX. Then, research it before I do the final draft and include details then. But sometimes, I am compelled to stop and figure that out during the rough-in stage. When I do, it’s likely to be a long list and for the final draft, I’ll have to choose the best of the list.

Rough out a scene: DOs

Do worry about finding the heart of the scene. Where is the pivot point, the emotional fulcrum upon which the scene rests. I must find that emotional heart during this stage, or I won’t have the excitement needed to write it well.

Do worry about details. OK, I just said above do NOT worry about details. So, it just depends. Sometimes a scene doesn’t come alive for me with the details and sometimes it does. Scenes with lots of dialogue and not much action need dialogue details, but not scene details. Action-heavy scenes need the action bits in detail, but maybe it’s fine to skimp on the dialogue. You must decide what you need for each scene.

Rough out a scene: When to stop and write.

How much time do I spend on this stage? It varies.

When do I stop roughing it out and write the thing? It varies. Sometimes, I only need a sketchy, minimal rough to write from. But in my current WIP novel, I’m doing a lot of world-building as I go. That means I have to figure out the scenery, name anything important like buildings or landscape features, think of a history of the area, and then put my characters in that setting. For science fiction and fantasy then, it takes longer to rough out a scene. For romance or contemporary novels, this stage of writing may go quicker.

I know that I need to write the actual scene when I’ve roughed it out enough that I’m excited to write it. Instead of holding back any longer, the words just flow. Sometimes, I’ll print out the rough and just glance at it while I write. Sometimes, I’ll work directly in the file and just revise the rough into the finished draft.

In other words, this is one more tool to put in your writer’s toolkit. Rough out your scene until you can approach the actual writing with great enthusiasm and passion!

The post Rough Out a Scene: Goals, DOs, DON’Ts, and the Writing appeared first on Fiction Notes.

March 14, 2016

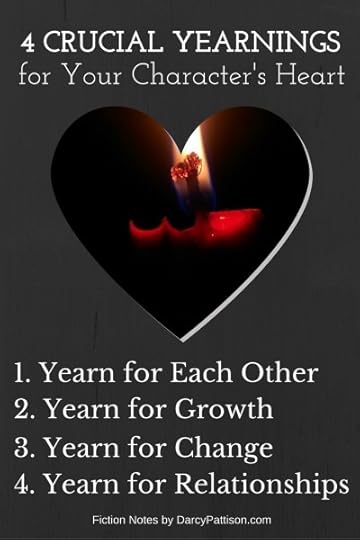

4 Crucial Yearnings to Enrich and Deepen Your Characters

at Highlights Foundation

Picture Books and All That Jazz - How to Write a Picture Book

Master Class in Novel Writing

When we develop characters, we know the drill. You must know what your character wants. But as I’ve worked on my current novel, I wasn’t getting to the heart of the character the way I wanted. So, I switched up the wording and asked, “What does this character yearn for?”

The idea of yearning goes deeper for me than just asking, “What does your character want?”

Yearning is a deep-seated emotional vacuum that needs to be filled. It’s more compelling because it permeates the character’s life. Also, it implies change and that’s crucial. If a character years to be more respected, then we can see that he progresses along the continuum somehow from NO RESPECT to WIDELY RESPECTED. The idea of “wanting” didn’t give me the character arc in the same way that “yearning” did.

We could say that a mystery is about a yearning for answers. But that’s not personal enough for a yearning. Answers fill a character’s want or need, but it’s hard to see it as fulfilling a yearning. A wish/need for excitement — as in a thriller or action/adventure — doesn’t feel quite personal enough to be called a yearning either. Yearnings are for character stories or subplots, places where raw emotions surface and are thwarted in the service of the story, so that the yearning becomes even deeper. Yearnings are personal.

Yearnings to Write By

Yearn for Each Other – Romance. The hero and heroine yearn for each other. When characters fall in love, it’s not enough just that they want each other. On some level, their relationship must be tested, thwarted, or put on a side burner. But underneath the yearning smolders. The continuum goes from NO RELATIONSHIP to INTIMATE RELATIONSHIP.

Yearn for Growth – Coming of Age. Maturation comes with deep yearnings to be more than you are at this point in time. Yearnings to become worthy, proud, skilled, competent, or loved. The continuum goes from NAIVE to EXPERIENCED.

Yearn for Change – Quest or Journey. Quests and journeys take characters on a journey from point A to point B. The most successful quest/journey stories, though, let the inner journey shape the path and the complications. In other words, the character’s yearning for change is a major plot driver. The continuum goes from STATUS QUO to MAJOR CHANGE.

Yearn for Connection – Relationships. . This can cover many types of stories: revenge, rivalry, underdog, love, forbidden love, sacrifice, discovery and ambition. When the story centers on positive relationships, the yearning is for connection. When it’s a negative relationship, the yearning is to dissolve the connections. The continuum goes from ISOLATED to CONNECTED.

By exploring my character’s deepest yearnings, I’ve easily created a character arc, which puts me a long way toward a plot, as well.

Related Post

Character Bait

Plot & Character

Celebrate Progress

Sports: Passionate characters

Characters: Bigger Than Life

.yuzo_related_post img{width:126.5px !important; height:88px !important;}

.yuzo_related_post .relatedthumb{line-height:15px;background: !important;color:!important;}

.yuzo_related_post .relatedthumb:hover{background:#fcfcf4 !important; -webkit-transition: background 0.2s linear; -moz-transition: background 0.2s linear; -o-transition: background 0.2s linear; transition: background 0.2s linear;;color:!important;}

.yuzo_related_post .relatedthumb a{color:!important;}

.yuzo_related_post .relatedthumb a:hover{ color:}!important;}

.yuzo_related_post .relatedthumb:hover a{ color:!important;}

.yuzo_related_post .relatedthumb:hover .yuzo__text--title{ color:!important;}

.yuzo_related_post .yuzo_text, .yuzo_related_post .yuzo_views_post {color:!important;}

.yuzo_related_post .relatedthumb:hover .yuzo_text, .yuzo_related_post:hover .yuzo_views_post {color:!important;}

.yuzo_related_post .relatedthumb{ margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 5px 5px 5px 5px; }

The post 4 Crucial Yearnings to Enrich and Deepen Your Characters appeared first on Fiction Notes.

February 29, 2016

Oliver Meets Rowdy: A Case Study of an Ongoing Promotion

at Highlights Foundation

Picture Books and All That Jazz - How to Write a Picture Book

Master Class in Novel Writing

One of my stories, THE JOURNEY OF OLIVER K. WOODMAN, is in a HMH reading textbook, Journeys.

It’s usually read in the spring and one activity that students often do is to send a laminated paper version of Oliver on a trip to visit folks.

Download the 2016 Lesson Plan pack, which includes Sample Chapters from five novels.(24 MB, zip file from Dropbox).

The Lesson Plan pack includes a simple paper pattern for Oliver. This is an example or case study of an easy ongoing promotion. First, I’ll explain what happened, and then we’ll look at how you can do the same for your book.

Interact with Readers

This year, Cynthia Wells, a teacher from Quitman, AR, contacted me and said that Kailin, her student, would like to send me her Oliver for a week’s visit. Of course, I can’t always do this, but this was a good year to say, “Yes!”

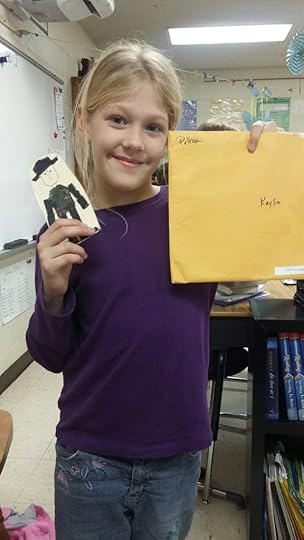

Kaylin sent her Oliver to visit me in my Blue Office. She’s holding the envelope I sent back.

Kaylin sent her Oliver to visit me in my Blue Office. She’s holding the envelope I sent back.

When a student sends an Oliver around, they ask people to take photos of Oliver in different places. See the Oliver Pinterest board.

Oliver Sees the Sights

Here are some things Oliver did with me.

Kailin’s Oliver met the BIG Oliver that lives in my Blue Office. | DarcyPattison.com

Kailin’s Oliver met the BIG Oliver that lives in my Blue Office. | DarcyPattison.com

Oliver joins a drummer and makes a bit of noise. | DarcyPattison.com

Oliver joins a drummer and makes a bit of noise. | DarcyPattison.com

Oliver visited the Genius Bar at the Apple store to get Darcy Pattison’s computer fixed.. | DarcyPattison.com

Oliver visited the Genius Bar at the Apple store to get Darcy Pattison’s computer fixed.. | DarcyPattison.com

Oliver Meets Rowdy

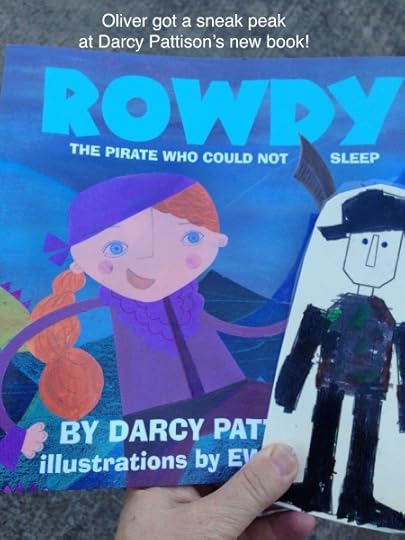

Of course, Oliver couldn’t leave without reading Rowdy, which is my Summer, 2016 book. The pirate captain, Miss Whitney Black McKee, and Oliver had a nice chat and compared adventures and travels. Oliver Meets Rowdy, Darcy Pattison’s Summer 2016 book. | DarcyPattison.com

Oliver Meets Rowdy, Darcy Pattison’s Summer 2016 book. | DarcyPattison.com

Preorder ROWDY now and it will be delivered on May 25

PURCHASE ORDERS

HARDCOVER

PAPERBACK

DIGITAL

KINDLE

iBOOK

ePUB

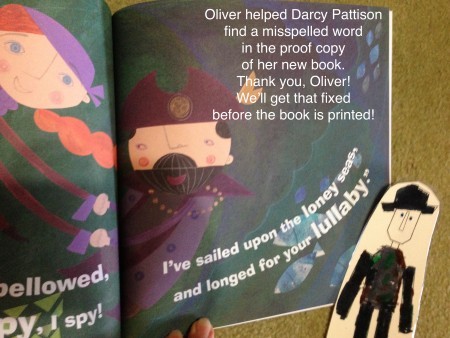

And then, Oliver settled in to read Rowdy’s story. Imagine Captain McKee’s dismay when Oliver found a misspelled word in her book! Oh, my! It was lucky that Oliver came along to save the day!

Oliver K. Woodman finds a misspelled work in Captain McKee’s story, ROWDY. | DarcyPattison.com

Oliver K. Woodman finds a misspelled work in Captain McKee’s story, ROWDY. | DarcyPattison.com

Finally, here’s Kailin reading another of my books, I WANT A DOG, to her class. A happy reader! That’s what we like to see!

Kailin was so excited to receive a new book, I Want a Dog, that she had to read it to the class. | DarcyPattison.com

Kailin was so excited to receive a new book, I Want a Dog, that she had to read it to the class. | DarcyPattison.com

Your Promotion

Here’s a couple lessons for your promotion.

Lesson Plans. Provide Downloadable Lesson plans on your website, Pinterest boards, etc.

Interact. When asked to interact with readers, do it if your schedule allows.

Fun. I took Oliver places that I thought would be fun. I didn’t worry about promotional possibilities while playing tour guide for Oliver. It was just for fun.

Generous. Be generous if you can. I sent along an extra paperback book, just for fun.

Permission. When the teacher contacted me, I asked and received permission to share the photos of the student.

Share. I’ll be sharing this post on Pinterest, Facebook, Twitter, etc. Be sure all your social media accounts are in order before you start something like this.

Thanks. I’ll be sure to thank the teacher for thinking about sending Oliver to visit!

The post Oliver Meets Rowdy: A Case Study of an Ongoing Promotion appeared first on Fiction Notes.

February 22, 2016

In Publishing, You Live or Die by Your Opinion

at Highlights Foundation

Picture Books and All That Jazz - How to Write a Picture Book

Master Class in Novel Writing

I once asked an editor if she regretted passing on the opportunity to become the publisher of the Harry Potter series.

The editor said, “In the publishing world, you live or die by your opinion. In spite of Harry Potter’s success, it still wouldn’t have been the right book for me to publish.”

In Your Opinion, What is Good Writing?

The first place you need to draw a line in the sand is one the question of quality. The quality of the story, the plotting, the characterization, the storytelling and so on is crucial to the success of a writing and publishing project. You need to listen tot he “still, small voice” that tells you this story needs another revision or that story measures up to the highest standard.

A sense of great stories is important to develop and most agree that a wide knowledge of the genre in which you write. If you want to write a picture book, you should read 100 picture books published within the last five years. If you want to write a YA novel, you should be familiar with the popular writers of the day. Of course, you can’t read 4000 novels in a year, so you’ll have to pick and choose. But notice what you like, enjoy, discard after a few chapters and so on. Develop a sense of what you like or don’t like. In short develop an appreciation of great writing. Give yourself something solid on which to base your opinion. Because you’ll live or die by it.

When I see really bad self-published children’s books, it’s most often from a person who doesn’t read children’s books. They just had a “great idea” and with no research or background in children’s literature, push through an awful book. I’ve actually had people tell me, “I’m not a writer. I just wanted to do this book.” That person’s project will die an early death because they didn’t educate their opinion.

In Your Opinion, Is this the BEST Writing You Can Do?

After writing a great story or novel, have you taken the time to let it cool off, to get feedback from trusted readers, and to take time to revise it to the best of your ability? Have you held anything back, or did you spend it all?

Author Annie Dillard, in her great essays, Write Till You Drop, wrote:

One of the few things I know about writing is this: spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.

After Michelangelo died, someone found in his studio a piece of paper on which he had written a note to his apprentice, in the handwriting of his old age: ”Draw, Antonio, draw, Antonio, draw and do not waste time.”

In your opinion, have to done your best? Then, send it out.

If not, fix it. But write, authors, write.

Answering Objection

BUT, you say. . .

My boy/girl friend didn’t like it.

My Significant Other didn’t like it.

My kid didn’t like it.

My agent didn’t like it.

My editor didn’t like it.

This genre isn’t selling right now.

No one buys books by authors from XXX.

I don’t have a HUGE social media following.

Blah, blah, blah.

Wrong, wrong, wrong.

Do YOU like what you wrote?

You live or die by your opinion.

If it’s not the best you can write, then fix it. Revise. Do whatever it takes to make it live up to your opinion.

If YOU like it, then send it out, and keep sending it out, until you find an editor who agrees with you.

Period.

The post In Publishing, You Live or Die by Your Opinion appeared first on Fiction Notes.

February 1, 2016

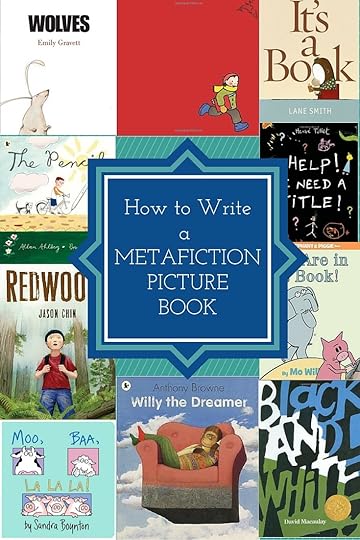

How to Write a MetaFiction Picture Book

Coming February 9!

PreOrder Now!

I’m working on a revision of my book, How to Write a Picture Book (Look for the new version in September). One section goes through various genres with tips on writing an ABC book, a narrative nonfiction, a picture book mystery, etc. One genre that I neglected in the first draft was metafiction picture books.

A Revealing Conversation between DH and Me

Me: I need to write a blog post about metafiction picture books.

Darling Husband (DH): What’s that?

Me: You know. Postmodern stuff.

DH: What?

Me: They are books that refer to themselves in some way. They break the concept of “book” in the story itself.

DH: Oh. Faux books.

Metafiction picture books are those that break the mold by making the reader aware that they are reading a book. Often fiction writers talk about the immersive book, and value stories that transport a reader to a story world and immerse them totally in the story. The reader’s surroundings disappear and they are deeply involved with the story.

Metafiction breaks that immersive experience. Why? In the theater, this is referred to as breaking the fourth wall. The stage has a back wall and two wings; the fourth wall is invisible wall that separates the audience from the stage. When an actor turns to the audience and makes comments, it’s breaking the fourth wall. The technique can be used to add information, set up irony, create humor or other purposes.

While metafiction isn’t new, it’s been more prevalent in the last few decades. Some say that it’s related to the postmodern philosophy. Read more about postmodernism here.

So, what is a metafiction picture book? Let’s look at some characteristics typical of this genre. Of course, you won’t use all of these in any given book. You can mix and match techniques to tell your story (or un-story). The best way to understand these is to read through a variety of the books suggested below.

Characteristics of a Metafiction Picture Book

Me: One reason I need to write this is because I’ve been trying to critique some manuscripts and having a hard time.

DH: You expect them to be a certain way and they aren’t.

Me: Well. Yes. There are rules about writing picture books.

DH: Are there?

Parody or irony.

Some metafiction picture books refer to folk or fairy tales, often with irony or parody.

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Book? By Lauren Child

Pastiche. Copying a certain style of art to create something very different, these are usually author-illustrator stories. Willy the Dreamer by Anthony Browne.

Story gaps. Sometimes the text has gaps that require readers to make decisions about the story and its meaning. Academics call this interdeterminancy. The Three Little Pigs by David Wiesner.

Multiple narrators or characters. The story includes multiple point-of-view characters, often with multiple story arcs. In Chloe and the Lion by Mac Barnett, illustrated by Adam Rex, the author, illustrator and main character each tell separate stories and talk to each other. The complex interaction has three separate endings.See also:

Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales by Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith

Black and White by David Macauley

Voices in the Park by Anthony Browne

Direct address to reader. When you use second person point-of-view and talk to the reader, the story can fall into the metafiction category.In a quick review of different points-of-view, you can usually figure out the story’s POV by looking at the pronouns.

1st person: I, me, my

2nd person: You, yours

3rd person: he, she, it, his, hers

In Warning! Do Not Open This Book, by Adam Lehrhaupt, the reader is warned against opening the book. When—of course—the child does open the book, the text provides other warnings.

See also: Thank You, Sarah: The Woman Who Saved Thanksgiving, by Laurie Halse Anderson,

Non-linear, non-sequential. Most narratives follow a certain time sequence. This happens first, and then that happens. There’s a beginning, middle and end. However, metafiction picturebooks create stories without a clear reference to time order. In Black and White by David Macaulay, each page is divided into four sections which tell different stories and it’s up to the reader to connect them. Or not.

Narrator becomes a character. The author or narrator of the story steps into the story and participates. In Chester, by Melanie Watts, a simple story devolves into an argument between a cat and the author about what story to tell.

Unusual book design or layout. Some metaficiton picture books have unusual typography, while others use a layout that breaks the story out of the page or book. Three Little Pigs by David Wiesner, has illustrations showing the pigs folding up a page and climbing out of the story onto a blank page. Or, they fold up a page into a paper airplane and take a ride.

Stories within Stories. No Bears by Meg McKinlay, Ella writes a book within the book.

Characters and narrators speak directly to the reader.

Sandra Boynton’s board book, Moo, Baa, La, La, La.

The text says,

“The pigs say, ‘la, la, la.’

‘No, no,’ you say, that isn’t right.

The pigs say, ‘Oink,’ all day and night.”

Characters who comment about their own or other stories. In Chester by Melanie Watt, the author and cat character go back and forth about the story. Among other shenanigans, the cat crosses out the author’s name on the cover and puts his own name.

Disruption of time and space relationships. Redwoods by Jason Chin. A boy picks up a nonfiction book about redwood forests and enters the forest.

Something makes the readers aware of what makes up a story. In Help! We Need a Title! By Herve Tullet, characters realize someone is watching them (that’s YOU, the reader) and decide to make up a story. In the end, they invite the author to help finish the story.

Mixing of Genres.

In A Book by Mordecai Gerstein, a girl runs into characters from different genres in a search for her own story. This allows the reader to learn about elements of different genres.

Metafiction + Creative nonfiction. Can you write a metafiction nonfiction picture book? Yes. These stories often mix informational text with fiction. No Monkeys, No Chocolate by Melissa Stewart and Allen Young features a couple of worms who make funny comments while the narrator explains where chocolate comes from. How to Write a Metafiction Picture Book | DarcyPattison.com

How to Write a Metafiction Picture Book | DarcyPattison.com

Writing a Metafiction Picture Book

DH: Actually, I do metaficiton.

Me: What? When?

Flashback to memory of DH telling bedtime stories to our kids:

“Once upon a time, there were three bears. Flopsy, Mospy and Peter Bear.”

Me: (Slapping forehead) Oh, my goodness. You’re a metafiction storyteller!

At least, there’s one in the family.

Know the Rules – Break the Rules

If you’ve read my book, How to Write a Children’s Picture Book, you’ll know most of the “rules” of writing a picture book. Break any rule that’s reasonable for the story, but have a reason to break it. You may want to inject humor, parody, information, or yourself into the story for a good reason. Do it. And do it boldly.

Metafiction Topics

While you can write about anything, often the topic of a metafiction picture book is to explain a book or some element of fiction or writing. That’s reflected in titles such as It’s a Book, There are No Cats in This Book, and Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Book?. Of course, if you try this, remember that you’ll have lots of competition.

Good Read Alouds

Make sure these are good read alouds because youngest readers may read these with adults to make sure it’s understood. Read more about how to make your story a good read aloud here.

Have fun

One of the main reasons to write a metafiction picture book is to have fun, to play with the genre. Do something unexpected, disrespectful, funny.

Critiquing Metafiction Picture Books

DH: Actually, I like a lot of the books you’re calling metafiction.

Me: Why?

DH: They’re unexpected. A surprise. They make me laugh. Kids love them.

An aside: In my household, it’s understood that I don’t have a sense of humor.

Slap stick? No, it’s not funny.

Potty jokes? Absolutely not.

Metafiction? I’m not laughing.

DH: Of course, it’s hard for you to critique metafiction manuscripts.

Me: (Groan. Why is he always right?)

DH: (Wisely, DH refrains from saying anything else.)

Authors, give your group (or editor) a heads up.

When I approach a critique of a picture book, I am always expecting a traditional story. So, it’s helpful if the author is aware of the type picture book they are writing and can tell the critique group, “This is a metafiction picture book.”

Readers, read the story in front of you.

I often read movie or book reviews and get aggravated because the review is more about the reader than the text. The reviewer talks about what they wanted or predicted and how those preconceptions were disappointed. That’s the danger in critiquing this special type of picture book. Especially for metafiction picture books, you must read the text in front of you. Be open to a new way of telling a story for kids.

Resources: Read More

Ann. Teaching Tips: Fun with Metafiction. July 30, 2015. Many Roads to Reading blog. Nice list of books and teaching tips.

Tantari, Sue. The Postmodern Picture Book and Its Impact on Classroom Literacy. C. 2014

Great explanation of metafiction picture books, including interactive elements, illustrations from selected books, charts and audio. If you’re totally new to this genre, start here.

Metafiction Picture Books to Study

Look for other titles by these authors, too.

Ahlberg, Allen. The Pencil

Barnett, Mac. Chloe and the Lion

Bingham, Kelly. Z is for Moose

Boynton, Sandra. Moo, Baa, La, La, La

Browne, Anthony. Willy the Dreamer

Child, Lauren. Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Book?

Chin, Jason. Redwoods

Freedman, Deborah. Scribble

Gerstein, Mordecai. A Book

Gravett, Emily. Wolves

Hopkinson, Deborah. Abe Lincoln Crosses a Creek

Lehman, Barbara. The Red Book

Macauley, David. Black and White

Schwarz, Viviane. There are No Cats in this Book

Scieszka, Jon and Lane Smith. Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales

Smith, Lane. It’s a Book

Spiegelman, Art. Open Me. . .I’m a Dog!

Stewart, Melissa. No Monkeys, No Chocolate

Tullet, Herve. Help! We Need a Title!

Watt, Mélanie. Chester

Willems, Mo. We Are in a Book

The post How to Write a MetaFiction Picture Book appeared first on Fiction Notes.

January 26, 2016

Review: The Art of Comic Book Writing

Coming February 9!

PreOrder Now!

One of the most puzzling, yet exciting formats for writers is the graphic novel. That’s the new name for comic books, or telling stories in a set of illustrated panels. In some writing a graphic novel is like writing a movie script, except the images are still instead of moving.

Writing a graphic novel comes with lots of questions.

What’s the standard format for a graphic novel manuscript?

Do you have to provide the illustrations?

How do you decide how many panels per page?

How do you pace a story across a couple pages?

Many of these questions relate also to writing children’s picture books, which are a combination of text and illustrations.

Finally, I have a resource I’d like to recommend to answer these questions: The Art of Comic Book Writing: The Definitive Guide to Outlining, Scripting, and Pitching Your Sequential Art Stories by Mark Kneece. Available as Kindle or paperback.

Writing a Graphic Novel or a Children’s Picture Book? Highly recommended resource for understanding how layout affects a story. | DarcyPattison.com

Writing a Graphic Novel or a Children’s Picture Book? Highly recommended resource for understanding how layout affects a story. | DarcyPattison.comNOTE: I didn’t receive a review copy on this book. I just found it at my local library and was captivated.

Kneece has taught comic book writing at the Savannah College of Design for over two decades and his expertise and experience shows. He has created eight graphic novel adaptations of The Twilight Zone, and has published numerous graphic novels and comics, including work for Hellraiser, Verdilak, Alien Encounters, Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight, and The Spirit.

Comics Tell Great Stories

Kneece begins with an emphasis on the story that you want to tell with hints on how to develop a story past a gag. You’ll see actual examples of a formatted script. Next comes a detailed look at a single page and how a story flows across the page. Templates for a 5-panel, 6-panel, 9-panel and 12-panel bring the page to life. Rough sketches illustrate Kneece’s points about how a story flows across these different panels.

With the basics out of the way, the book gets really interesting digging into dialogue, text, characters, pacing and more. This is a fantastic book for those writing picture books because everything he says here applies to both comics and children’s picture books.

I LOVE the pacing chapters.

In Part 1, pp125-127, there’s a great example of revising for pacing, emphasis and impact. The question is where to expand the story with more details and where to compress the story for impact. This is one of the best illustrations of pacing an illustrated story that I’ve seen.

And then, in Part 2, there’s a great example of a story with a boy hears an ice cream truck. The top row is 4 panels.

Panel 1: A boy is playing with a toy rocket. A few musical notes intrude into the frame.

Panel 2: grass and musical notes

Panel 3: grass and musical notes that are trending upward

Panel 4: musical notes dance past the trunk of a large tree.

In other words the 4 panels operate more like one large panel that spans four panels. But the choice to create four panels – a quad-tych, if you will – adds energy to the story. It’s brilliant.

If you’re an illustrator of children’s books, you need to study this book. If you write children’s picture books, you need to study this book. Comic books writers and illustrators, it’s definitely the best text I’ve seen on the topic. Highly recommended.

The post Review: The Art of Comic Book Writing appeared first on Fiction Notes.

January 18, 2016

5 AMAZING Reasons to Write a Short Story: Develop and Market Your Novel

Coming February 9!

PreOrder Now!

I’m working on a trilogy of science fiction stories and they began with a short story.

A couple years ago, in preparation for attending a conference, I wrote a sff short story. It was accepted for publication in a Fiction River anthology and became my first ever fiction publication for adults. But I knew even as I wrote it that it was backstory for the YA trilogy that I had planned.

That story has had repercussions throughout my novels and here’s how a short story could benefit YOUR novel.

Backstory. The backstory is everything that happens before the opening scene of your novel. It involved family, parents, culture, historical events and so on. Why are you starting your novel at this particular place and time? Because it’s the beginning of the “day of change.” Your novel needs an exciting start. It doesn’t need a long historical tome that explains why this or that is important. See more about great openings. However, it is crucial that YOU, the author, know all that stuff.

Instead of dryly writing up a world history, why not write a short story about it? My short story introduces the first time that humans meet the aliens from the planet Rison. Of course, the main characters in that story are important in the novel: they are the parents of the novel’s main character. It’s their love story and the reason for the main character’s existence as a half-human/half-alien boy. And of course, that identity reverberates throughout the novel.

Excitement. Writing the short story, the worlds poured out. Hey, it didn’t matter if I “got it right” because I was writing this just for me. Yes, there was a conference, but really, I thought I’d be the only one to read it. That gave me great freedom to write and explore the possibilities of the world I’d imagined. What fun! I went places that surprised me in the short story. I think that freedom, the fun, and the very loose attitude toward the writing was helpful in developing the foundation for my novel.

Voice. Besides writing something fun, the story story was an opportunity to test out a certain voice. I reached for a scientific feel that would firmly pull my story into the science fiction camp instead of fantasy. Short stories are an easy way to test voice without a big commitment.

Publication. The fact that the short story was published was a bonus! If you write for adults, there are many such markets. At times, YA writers can also cross over to these markets. If you write for middle grade, good luck; there are few markets for short stories for that audience.

Marketing. Finally, I see these short stories as fiction that I can give away to garner interest in the novels. With giveaways such a prevalent strategy these days, it makes sense to plan what to give away. This will be better than giving away a full book, but it should do as good a job in getting readers interested in the story and my writing.

I find myself needing to write another short story to accompany Book 2, and for much the same reason. The backstory needs more depth and concrete details. I’ve been trying this week to hammer out this and that, without much success. And then, I remembered the story story as a tool in my writer’s tool box. I’ll be writing at least one and maybe two or three short stories this coming week.

The post 5 AMAZING Reasons to Write a Short Story: Develop and Market Your Novel appeared first on Fiction Notes.

January 12, 2016

Preview Widget: Amazon Book Marketing Tool

Coming February 9!

PreOrder Now!

Amazon is now providing a new twist on book marketing with an embeddable widget that allows a preview. Word is that it looks great on mobile or desktop. And Wow, is it easy to implement!

Here’s an example of how it looks for a picture book.

And an example of how it looks for a novel. It allows you to read a couple chapters before you decide if you want to buy or not.

Want your own widget? Here’s Amazon’s simple 1-2-3 step process to put such a widget on your website. The screenshots make it easy. Are you an Amazon affiliate? If you embed the code on your website, the widget allows you to add your affiliate id number. This is a slick, dead-simple promotional tool!

I did try it for my forthcoming book, BURN: MICHAEL FARADAY’S CANDLE, which is now available for preorder. Unfortunately, the widget wasn’t available for it. I also tried adding the link to Facebook, but that didn’t work either.

The post Preview Widget: Amazon Book Marketing Tool appeared first on Fiction Notes.