Darcy Pattison's Blog, page 30

November 13, 2013

What’s YOUR Biggest Writing Problem Today?

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

Nook

Today, I want to listen to you. I have on my big listening ears!

What is the biggest problem you are having with your current work-in-progress?

Please describe it in the comments below.

November 12, 2013

3 Simple Ways to Use Photos to Establish Characters

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

Nook

I need my characters to come to life quickly for me and this time, I’m trying a shortcut. Photos.

It’s easy to go to google.com/images or flickr.com and search for images that might fit your characters. Start with a gender (male/female) and age (child, teen, adult, senior, 30s, 40s, etc).

Ethnic background. For my story, I knew that one character had a mixed-ethnic background, combining Asian and Caucasian heritage. What I didn’t know was how strong the genes might be on either side of that, and how they might change for different Asian/northern European mixes. Even better, I found personal stories of growing up multicultural. Sites like this make it easier to add a unique richness to a character, avoiding stereotypes that might result from a specific ethnic background.

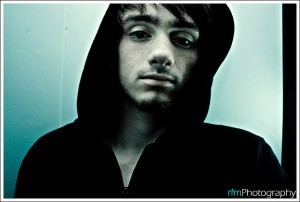

Physical description. Frankly, my physical descriptions have gotten stale. I’m not particularly visually oriented and inventing characters physical looks is usually last on my list of writing chores. I keep thinking, “But it’s the inner character that matters.” Of course. But physical looks matter, too. I took several photos and really observed closely, trying for fresh descriptions. Here are three boys. How would you describe each one to make him come alive as a character?

Historical photos. Photos are gold when you are writing historical fiction. Notice details of clothing, shoes, hair styles, setting, surroundings, etc. and use these details as you write.

1971 Tallahassee Civil Rights march. Notice the variety of clothing–great stuff to add to your story.

What’s your favorite way to use photos to establish characters?

November 11, 2013

Get Your Tone Right

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

Nook

“Young man, don’t speak to me in that tone of voice!”

When you see that bit of dialogue, you know that a boy is talking sarcastically or disrespectfully. We understand that it’s not just the words said, but it’s how the words are used that conveys an attitude.

Humor, irony, satire, pleasantness, excitement, righteous indignation–the audience’s anticipated reaction is what determines the tone with which you write a particular piece. Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown has a soothing tone; Captain Underpants by Dave Pilkey has an irreverent, comical tone; Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse has a spare, restrained tone that matches the mood of the Dust Bowl.

I’ve been dealing with tone because I’ll have a nonfiction piece, “Don’t Lick That Statue,” in the June 2014 issue of Highlights Magazine for Children. When you turn in this type of manuscript, they require a letter from your sources that states the article is “appropriate in tone and content” for a young reader. Content is easy: just check and recheck your facts, ma’am. Tone is not so easy. What does it mean, anyway?

Definition of Tone of Voice

How would you describe the tone of this photo taken at dawn near the Alamo?

Tone is the atmosphere that holds a story together; it permeates the narrative, setting, characters and dialogue. It can also shape a reader’s response. In a mystery with a dark, gothic tone, the reader is meant to be on the edge of fear.Tone gives the author subtle ways to communicate emotional content that can’t be told by only looking at what words mean. We also need to look at connotations and how words work within the context of the story.

One of the first ways to get a handle on controlling the tone of voice is to look at the adjectives and adverbs within your story. Specific details can fill the reader’s head with clues about how to interpret the story, but without a physical voice. The tone can be cued by adjectives or adverbs: quietly, he said; angrily, he said; sadly, he said. More experienced writers can convey the same tone with connotations of words and not have to rely on these adverbs.

In other words, the missing words–quietly, angrily, sadly–are communicated by every tool in the writer’s arsenal. That’s a frustrating statement for beginning writers: it’s too abstract. Let’s make it a bit more concrete.

Creating Tone of Voice

Before you begin writing, you should have a tone of voice in mind, so you will be consistent. The tone of voice should shape the story at all stages.

The opening, especially, should begin with the right tone, so the reader knows what sort of story will follow. Descriptions, dialogue, or even first-person statements are all welcome. The opening scene should give the reader a feel for the book that will be consistent throughout. A dark, gothic mystery should never morph into an action/adventure or a fairy tale. Within the dark, gothic mystery, there is room for variation, but there are also boundaries for when it moves outside the right tone. Set your story’s tone early and stick with it.

Recognition and Consistency

Once you have something written that captures the character, the voice of the story and the tone of the story, then you must do two things. First, recognize when that voice and tone is present and working; second, learn to be consistent with the voice and tone.

Put the work aside for as long as you can stand it, then read it with an eye toward where the voice, tone and character are working or not working. Read it out loud, and pay attention to places where there’s a “bump” for some odd, almost indefinable moment. That’s probably a tone or voice problem. Changing mood is fine; changing tone is not. On a very simple level this means that you can’t start a story with a dreamy stream-of-consciousness and end with an action-packed thriller.

Consistency is important even when a story has multiple points of view. For novels that switch back and forth between male and female characters, the tone must still be maintained.

Crafting your Story’s Tone

While much of the discussion about tone of voice revolves around abstract issues, there are some concrete things that can be considered.

Choice of details. Choose the sensory details that bring a story to life. Does it matter that Dracula wears black? Of course! Be sure to include as many senses as possible, pulling in visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory and tactile details.

Plot and organization. Often, picture book stories have simple refrains—which present a reassuring tone by suggesting that there is order in the world. The organization of the text always returns to a phrase that is important; the child knows you’ll get to that point again in the story and feels the ordering of events in the story, which reinforces the tone.

Language and vocabulary. The language and vocabulary used must also support the tone of a story. Choosing the right word is paramount, but also consider how the words work in context. Connotations are words speaking to other words in a story. You may want to alliteration, assonance, or other literary techniques to make certain words resonate. But the technique should be subtle enough to work without calling attention to itself.

Dialogue. Dialogue can carry tone of voice, too. Avoid stilted and extended sections of talking heads. Instead, work for a snappy exchange—or whatever is appropriate for your tone. Sometimes, it helps to be intentional and say to yourself, “My story’s tone is XXX and that means my dialogue should be XXX.” Then evaluate to see where you need to adjust.

Write Your Story Your Way!

If all the above feels too abstract, if you want more detailed how-to instructions, if you have trouble recognizing voice much less tone of voice, you aren’t alone. Yet, editors and teachers of writing can’t be more specific. “It depends. . . ,” they say. It always depends on the story, the characters, the setting, the author’s intent, and so many other minor and major decisions about a story.

The tone is the end result, but it is also the beginning. The author must solve the problem of tone of voice in different ways for each story they tell. You have an arsenal of weapons: setting, characterization, language, rhythm, vocabulary, plot, organization. In the end, there are no right or wrong answers; there are only stories that work or don’t work.

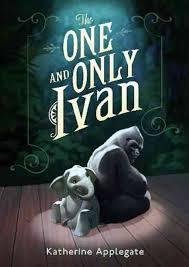

Can you suggest stories that portray a certain tone? How would you describe the tone of IVAN, THE GREAT AND MIGHTY? Of HUNGER GAMES?

November 8, 2013

Revising Bird

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

Nook

Guest post by Crystal Chan

Crystal attended a novel revision retreat a couple years ago and the result is this amazing book, her debut. Here, she talks about her revision process. –Darcy

The biggest editing challenge that I encountered my forthcoming novel, Bird (January 28, 2014, Atheneum. PREORDER NOW!) was trying to put too much “stuff” into the story. The protagonist, Jewel, is mixed race, in Iowa; her Jamaican side/grandfather believes there’s a duppy (read: ghost) roaming around the house; she was born on the same day that her brother died and there’s a load of unresolved grief in the family; a new boy comes to town with the same name as her dead brother and looks a little like how he would have looked like had he lived; and this boy is unsettling the layers of silence in the family. Enough, right?

Wrong. I really wanted to add some cool stuff with the mother’s backstory, and I wanted to do so to highlight the mixing of cultures that Jewel needed to wade through, as well as to explain why Jewel’s mom was so emotionally distant. For those who care to know, Jewel’s mother had an aunt in a small town along the Texan border, and years ago this aunt, right after she gave birth to their first child, realized her husband (the mom’s uncle) was cheating on her, and she ran out of the house in grief, and they found her, dead, along a riverbank. The baby died soon afterward. The townspeople said that her aunt had turned into the Llorona, a Mexican banshee who drowned her children, regretted it, and goes around killing adults in revenge (I’m skipping a lot of details here, bear with me).

Anyway. This backstory, as interesting and pertinent to Mexican culture as it might have been (the Llorona is well, well known among Mexicans), was simply dragging down the story line, and much worse, muddling the story line entirely. I tried to make this work for at least three drafts, as I really wanted Jewel’s Mexican side to also get a showing in the story, but eventually (and with the utmost blessing of my editor) I opted to cut it out.

And I watched the story shine.

I found other, more subtle, ways to bring out Jewel’s Mexican heritage and explain her mother’s emotional distance – which was a lesson for me. There’s no one right way to make a story work. If one way is stuck, there’s always another way. But that requires being willing to backtrack, look at options, go back to the drawing board if necessary – which is scary (and humbling), since we invested so darn much in what we’ve already created. But then again, the question begs to be answered: Why are we writing? To push what we want, how we want it? Or to tell a story in the best way it needs to be told? Yes, sometimes writing that story means bearing down and slugging through the next version of the manuscript. Other times, though, it means opening our hands and letting go.

Crystal Chan

Crystal:) www.crystalchanwrites.com

PS – and good news! Bird just sold in Romania!

November 7, 2013

The 13-Year Picture Book: Anne Broyles

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

Nook

guest post by Anne Broyles

Anne attended a novel revision retreat a couple years ago. Switching from novels to picture books, she applied all the principles of great writing and the result is an amazing story. Here, she talks about her revision process. –Darcy

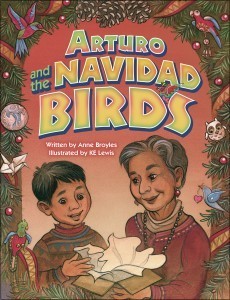

Arturo and the Navidad Birds

With the publication of my third picture book, I took the chance to reflect on the thirteen-year period that brought Arturo and the Navidad Birds to bookstores. If I’d known ‘way back then what I have learned over these years, the book might have been published earlier but I apparently needed time to learn these lessons!

Mouse Ornament

Christmas 2000: As I was decorating our Christmas tree with our German foreign exchange daughter, explaining the stories behind many of our one-of-a-kind ornaments, I had the initial idea of a picture book about a grandmother sharing family history with her grandson as they—surprise!—decorate a Christmas tree. As soon as the boxes of ornaments were empty and our tree was complete, I stole off to write four pages of notes, listing possible ornaments and their stories. Working title: The Memory Tree.1/2001: On breaks from other projects, I mulled over the grandmother and grandson. Who were they and what sort of relationship did they have? Having recently studied Spanish in Costa Rica, I decided to root my story in a family with a Costa Rican-born grandmother and American-born grandson.

2/2001: I spent way too much time figuring out a chronology of the grandmother’s life. How much time did I spend on Arturo’s character? Not enough!

7/2001: I wrote the first draft (2000 words in 3 hours) in English with occasional Spanish words, and compiled a list of possible publishers. The story belonged to Abue Rosa, focusing on her back-story and the ornaments’ history. Arturo was not fully developed in this wordy draft.

9/2001: An editor friend gave her opinion on the first draft (“the idea holds a lot of appeal”) but wondered about the chronology of Abue Rosa’s too-complicated back-story. I realized I needed to get into Arturo’s head more. Around this time, I also asked a Costa Rican colleague for comments on language/cultural accuracy and made some small changes. I also asked several Hispanic friends what they called their grandmothers and discovered a great variety as each family chose its own nicknames (English-speaking North American families may call grandmothers Grammy, Nonna, Memaw, Granny Sue, Oma, etc.)

2003: I sent The Memory Tree to POCKETS magazine. Rejection #1.

2004-2009: Although this wasn’t my main work-in-progress, I did share the story with my two critique groups and a writing revision retreat. With their feedback, I realized that I had a “talking heads” story that was too “quiet.” The numerous ornament stories slowed down the action so I deleted all but a few decorations. The word count decreased, little by little, from 2000 to 933 words.

One colleague commented that her son would never be so calm, but would find ways to play with ornaments. Her words helped me unlock Arturo’s character— he finally came to life as I added the broken bird ornament to give the story tension and meaning. Up until then it had been “Abue Rosa and Arturo decorate the tree together. Isn’t that sweet?” Now, the story had action/reaction, conflict and resolution.

One reader disliked The Memory Tree title, which “sounded like a genealogical tree.” I liked her suggestion and changed to “The Empty Christmas Tree”.

In 2008, I sent the manuscript to two editors. One mentioned “a sweet plot”, the other “liked the Costa Rican references and cultural context” but “the initial string of remembrances isn’t enough to pull me into the story.” Rejections #2 and 3.

Between 2009 and 2011. I tightened the story to 738 words and sent the manuscript to six more editors for rejections #4 and 5, three no response even with follow-up, and in 2/2010: Pelican’s Nina Kooij said they would hold the submission on their “possibles list,” but I was free to submit elsewhere.

2010-2011: Eleven years had passed since my initial idea. Was this bilingual, multicultural, holiday book fit too narrowly defined? I put away “The Empty Christmas Tree” and worked on other projects.

1/12: I almost didn’t open my SASE from Pelican since it had been two years since I last heard from them. Nina Kooij asked if the book was still available. Yes, yes, yes!

3/12: Pelican requested a new title “that implies the Hispanic culture.” I compiled a list of 22 titles (my own and friends’ suggestions) and tweaked the manuscript, making small changes that better reflected Hispanic culture. They chose Arturo and the Navidad Birds, which I like because it shows the protagonist, his family’s cultural and language background, and the symbols of the problem Arturo must solve.

5/12: Pelican decided to publish Arturo and the Navidad Birds with my English-with-a-smattering-of Spanish text and a separate all-Spanish text. I cut 100 words to make room for the Spanish text.

7/12: Once I had a complete Spanish translation, I emailed numerous Spanish-speaking friends and professional resources for their opinions. Their responses (we would say this instead of that; we don’t use this phrase in our country) convinced me to make the setting more generically Central American or Mexican. I altered some words/phrases to fit this vision.

9/12: I signed a contract with Pelican.

9/2012-3/2012: I worked with my editor and the illustrator to coordinate text and art. KE Lewis’ lovely paintings brought depth to my words, and I especially love how she showed Abue Rosa’s memories in sepia with the contemporary story in brighter colors. There are lots of details for young readers to discover in the book’s pages, and I was reminded of how important is the illustrator’s contribution to a picture book.

9/2013: Pelican released Arturo and the Navidad Birds.

In hindsight, I realize that my initial idea was more setting than plot. Until I knew both Arturo and Abue Rosa, the manuscript was an exercise in getting to know my characters and making the setting real in my mind. Once I identified a clear problem and brainstormed ways Arturo could try to solve the problem, the story worked. I cut two-thirds of the length, tightened the plot, layered more of Abue Rosa’s culture into the story and built the story’s tension up to Abue Rosa’s statement: “People are more important than things.”

In hindsight, I realize that my initial idea was more setting than plot. Until I knew both Arturo and Abue Rosa, the manuscript was an exercise in getting to know my characters and making the setting real in my mind. Once I identified a clear problem and brainstormed ways Arturo could try to solve the problem, the story worked. I cut two-thirds of the length, tightened the plot, layered more of Abue Rosa’s culture into the story and built the story’s tension up to Abue Rosa’s statement: “People are more important than things.”

And it only took me thirteen years to get these 32 pages right!

– Anne Broyles

Anne Broyles

Bio: Anne is the author of ARTURO AND THE NAVIDAD BIRDS, PRISCILLA AND THE HOLLYHOCKS (Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People, Bank Street College’s The Best Children’s Books of the Year, and Massachusetts Book Awards recommended reading list) and SHY MAMA’S HALLOWEEN (Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People, Teacher’s Choice Award and the McNaughton Award). She lives north of Boston with her husband, two cats

and an old black dog named Thor. For more, see AnneBroyles.com

November 6, 2013

Point of View: Inside a Character’s Head

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

Nook

How does an author take a reader deeply into a character’s POV? By using direct interior monologue and a stream of consciousness techniques.

This is part 3 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series.

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

Going Inside a Character’s Head, Heart and Emotions

Omniscience.Jauss says, “In direct interior monologue, the character’s thoughts are not just ‘reflected,’ they are presented directly, without altering person or tense. As a result, the external narrator disappears, if only for a moment, and the character takes over as ‘narrator.’” (p. 51)

Omniscience.Jauss says, “In direct interior monologue, the character’s thoughts are not just ‘reflected,’ they are presented directly, without altering person or tense. As a result, the external narrator disappears, if only for a moment, and the character takes over as ‘narrator.’” (p. 51)

Here, “. . . the narrator is not consciously narrating.” In much of IVAN, he is consciously narrating the story. Sometimes, it might be hard to distinguish the difference because the character and narrator are the same, and it’s written in present tense (except when he is telling about the background of each animal). This closeness of the character and narrator is one reason to choose first-person, present tense. But there are still times when it is clear that IVAN is narrating his story.

But there also times when that narrator’s role is absent. In the “nine thousand eight hundred and seventy-six days” chapter, Ivan is worried about what Mack will do after the small elephant Ruby hits Mack with her trunk:

“Mack groans. He stumbles to his feet and hobbles off toward his office. Ruby watches him leave. I can’t read her expression. Is she afraid? Relieved? Proud?”

The last three questions remove the narrator-Ivan and give us what Ivan is thinking at the moment. The direct interior monologue gives the reader direct access to the character. With a third person narrator, those rhetorical questions might be indirect interior monologue; but here, because of the first person narration, it feels like direct interior monologue.

Or, in the “click” chapter, Ivan is about to be moved to a zoo:

The door to my cage is propped open. I can’t stop staring at it.

My door. Open.

The first two sentences still feel like a narrator is reporting. But “My door. Open.” feels like direct access to Ivan’s thought at that precise moment. He’s not looking back and reporting, but this is direct access to his thoughts.

A last technique for diving straight into a character’s head is stream-of-consciousness. Jauss says, “. . . unlike direct interior monologue, it presents those thoughts as they exist before the character’s mind has ‘edited’ them or arranged them into complete sentences.” (P. 54)

When Ivan is finally in a new home at a local zoo, he is allowed to venture outside for the first time. The “outside at last” chapter is stream-of-consciousness.

Sky.

Grass.

Tree.

Ant.

Stick.

Bird. . . .

Mine.

Mine.

Mine.

What the reader feels here is Ivan’s wonder at the great outdoors. It’s a direct expression of Ivan’s joy in being outside after decades of being caged. We are one with this great beast and it gives the reader joy to be there.

Or look at the “romance” chapter, where Ivan is courting another gorilla.

A final note: Sometimes, an author breaks the “fourth wall,” the “imaginary wall that separates us from the actors,” and speaks directly to the reader. This is technically a switch from 1st person POV to 2nd person POV. But it is very effective in IVAN in the second chapter, “names.” Here, Ivan acknowledges that you—the reader—are outside his cage, watching him. It was a stunning moment for me, as I read the story.

“I suppose you think gorillas can’t understand you. Of course, you also probably think we can’t walk upright.

Try knuckle walking for an hour. You tell me: which way is more fun?”

Do stories and novels have to stay in one point of view throughout an entire scene or chapter? No. Not if you are thinking about point of view as a technique to draw the reader close to a character or shove the reader away. You can push and pull as you need. You can push the reader a little way outside to protect his/her emotions from a distressing scene. Or you can pull them into the character’s head to create empathy or hatred. You can manipulate the reader and his/her emotions. It’s a different way of thinking about point of view. For me, it’s an important distinction because my stories have often gotten characterization comments such as , “I just don’t feel connected to the characters enough.” I think a mastery of Outside, Outside/Inside, and Inside point of view techniques holds a key to a stronger story.

In the end, it’s not about the labels we apply to this section or that section of a story. These techniques can blur, especially in a story like IVAN, written in first person, present tense. Instead, it’s about the reader identifying with the character in a deep enough way to be moved by the story. These techniques–such a different way to think about point of view!–are refreshing because they give us a way to gain control of another part of our story. These are what make novels better than movies. I’ve heard that many script-writers have trouble making the transition to novels and this is the precise place where the difficulty occurs. Unlike movies, novels go into a character’s head, heart and mind. And these point of view techniques are your road map to the reader’s head, heart and mind.

This has been part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Inside: Deeply Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

November 5, 2013

Point of View: Outside/Inside a Character’s Head

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

Nook

Partially Inside a Character’s Head: OUTSIDE AND INSIDE POV

How deeply does a story take the reader into the head of a character. Many discussions of point of view skim over the idea that POV can related to how close a reader is to a reader. But David Jauss says there are two points of view that allow narrators to be both inside and outside a character: omniscience and indirect interior monologue.

This is part 2 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Here are links to parts 2 and 3.

Outside

Outside/Inside

InsideThese posts are inspired by an essay by David Jauss, professor at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock, in his book, On Writing Fiction: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom About Craft. I am using Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Omniscience. Traditionally, “limited omniscience” means that the narrator is inside the head of only one character; “regular omniscience” means the narrator is inside the head of more than one character.

Omniscience. Traditionally, “limited omniscience” means that the narrator is inside the head of only one character; “regular omniscience” means the narrator is inside the head of more than one character.

I love Jauss’s comment: “I don’t believe dividing omniscience into ‘limited’ and regular’ tells us anything remotely useful. The technique in both cases is identical; it’s merely applied to a different number of characters.”

He spends time proving that regular omniscience never enters into the heart and mind of every character in a novel. A glance at Tolstoy’s WAR AND PEACE, with its myriad of characters is enough to convince me of this truth.

Rather, Jauss says the difference that matters here is that the omniscient POV uses the narrator’s language. This distinguishes it from indirect interior monologues, where the thoughts are given in the character’s language. This is a very different question about POV: is this story told in the narrator’s language or the character’s language?

In IVAN, this is an interesting distinction because Ivan is the narrator of this story; it’s told in his voice. But as a narrator, there are times when he drops into omniscient POV. In the “artists” chapter, Ivan reports:

“Mack soon realized that people will pay for a picture made by a gorilla, even if they don’t know what it is. Now I draw every day.”

Ivan tells the reader what Mack is thinking (“soon realized”) and even what those who purchase his art are thinking (“even if they don’t know what it is”). Then, he pulls back into a dramatic reporting of his daily actions. Notice, too, that he makes this switch from dramatic POV to omniscient POV within the space of one sentence. And the omniscient POV dips into two places in that sentence, too.

Because Mack is Ivan’s caretaker and has caused much of Ivan’s troubles, the reader needs to know something of Mack’s character. This inside/outside level is enough, though. The author has decided that a deep interior view of Mack’s life isn’t the focus of the story. It’s enough to get glimpses of his motivation by doing just a little ways into his head.

Indirect Interior Monologue

Another technique for the narrator and reader to be both inside and outside a character is indirect interior monologue. Here, Jauss says that the narrator “translates the character’s thoughts and feelings into his own language. “ (p. 45) The character’s interior thoughts aren’t given directly and verbatim. This is a subtle distinction, but an important one.

Interior indirect monologue usually involves two things: changing the tense of a person’s thoughts; and changing the person of the thought from first to third. This signals that the narrator is outside the character, reflecting upon the character’s thoughts or actions.

They are all waiting for the train. (dramatic)

They were all waiting reasonably for the train. (Inside, indirect interior monologue)

The word “reasonably” puts this into the head of the narrator, who is making a judgment call, interpreting the dramatic action.

Interior indirect monologue most often seen with a third-person narrator reflecting another character’s thoughts. But in Ivan, we have a first-person narrator. Applegate stays strictly inside Ivan’s head, except for a few passages where Ivan reports indirectly on another character’s thoughts. Because the passages are already in present tense, she doesn’t have that tense change to rely on.

Here’s a passage that could have been indirect interior monologue but Applegate won’t quite go there. Stella is an elephant in a cage close to Ivan.

“Slowly Stella makes her way up the rest of the ramp. It groans under her weight and I can tell how much she is hurting by the awkward way she moves.”

By adding “I can tell. . .” it stays firmly inside Ivan’s head. He tells us that this is true only because Ivan makes an observation. The story doesn’t dip into the interior of the other characters.

But there are tiny places where the interior dialogue peeks through. This from the “bad guys” chapter. Bob is Ivan’s dog friend; Not-Tag is a stuffed animal; and Mack is Ivan’s owner.

“Bob slips under Not-Tag. He prefers to keep a low profile around Mack.”

Ivan can only know that Bob “prefers” something, when he, as the narrator, dips into Bob’s thoughts.

But indirect interior monologue is also used by a first person narrator to report his/her prior thoughts. When the first person narrator tells a story about what happened in his past, he is both the actor in the story and the narrator of the story. Ivan tells the story of his capture by humans over the course of several short chapters. It begins in the “what they did” chapter:

“We were clinging to our mother, my sister and I, when the humans killed her.”

While Ivan’s story is most present tense, this is past tense because Ivan is reporting on prior events. Even here Applegate refuses to slip into interior indirect monologue. Instead, she just presents the facts in a dramatic manner and lets the reader imagine what Ivan felt. It’s interesting that withholding Ivan’s thoughts here evoke such an emotional response in the reader.

On the other hand, in “the grunt” chapter, Ivan tells about his family. Again, he is the narrator telling about a past event when he was a main character of the event:

“Oh, how I loved to play tag with my sister!”

This could be called direct interior thought, but because he’s narrating a past event, it’s indirect interior thought. Otherwise, he would say, “Oh, how I love to play tag with my sister!”

Or from the “vine” chapter, where Ivan talks about his thoughts after being captured by humans:

“Somehow I knew that in order to live, I had to let my old life die. But sister could not let go of our home. It held her like a vine, stretching across the miles, comforting, strangling.

We were still in our crate when she looked at me without seeing, and I knew that the vine had finally snapped.”

If this was direct interior, it would be:

“Somehow I know that in order to live, I must let my old life die.”

Applegate could have chosen to stay inside Ivan, but here, she pulls back so the reader isn’t fully inside this emotionally disturbing moment. She uses indirect interior monologue, instead of direct.

As Jauss says about a different passage, but it applies here, “This example also illustrates the extremely important but rarely acknowledged fact that narrators often shift point of view not only within a story or novel but also within a single paragraph.” (p.50)

This has been proclaimed a mistake in writing point of view, but Jauss says it’s a normal technique. We dip into Mack’s point of view, but then pull back to a dramatic statement about what Ivan is doing.

Indirect interior monologue often includes “rhetorical questions, exclamations, sentence fragments and associational leaps as well as diction appropriate to the character rather than the narrator. “ (p. 49) In one of my novels, I used a lot of rhetorical questions as a way to get into the character’s head and an editor complained about it. Now, that I know why I was using it (as a way to manipulate how close the reader was to the character), I could go back and use a variety of techniques. Knowledge of fiction techniques is freeing! Tomorrow, we’ll look at how to go deeply into a character’s head, heart and emotions.

This is part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Join us tomorrow for the final part of the series, Inside: Going Deep into a Character’s Head.

This has been part 2 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Inside: Deeply Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series.

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

November 4, 2013

Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

A story’s point-of-view is crucial to the success of a story or novel. But POV is one of the most complicated and difficult of creative writing skills to master. Part of the problem is that POV can refer to four different things, says David Jauss, professor at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock, in his book, On Writing Fiction: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom About Craft.

This is part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Here are links to parts 2 and 3.

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

Definitions of Point of View

Your personal opinion. You might say, “From my point of view, that’s wrong.”

The narrator’s person: 1st, 2nd, or 3rd.

The narrative techniques: “omniscience, stream of consciousness and so forth”

“. . .the locus of the perception (the character whose perspective is presented, whether or not that character is narrating)” (p. 25)

The first definition is a personal, not a literary one, so it doesn’t apply here. The second definition (the narrator’s person) is perhaps the most widely discussed, but Jauss says it isn’t helpful to a writer as s/he approaches a story. In fact, what often happens is these definitions collide and the generally accepted wisdom is that you must stay in only one POV, you can’t use some techniques in some POVS, and the narrator is a side-issue. These conventional rules, though, conflict with actual practice, says Jauss. Further, they prevent writers from controlling one of the most important aspects of fiction: how close the reader feels to the characters. (p. 26, 36)

I love the idea that point of view is a technique: it is one of the tools in our writer’s tool box that we can pull out as needed to accomplish something in a story. I love the idea that point of view allows you to pull the reader closer to the characters or to shove them away from the character. Right away, Jauss has me. And it only gets better from here. More complicated, but better.

Let’s discuss point-of-view, and use Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Let’s discuss point-of-view, and use Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Traditional Point of View

Jauss points out that traditionally point-of-view is discussed in terms of person, and defined by the pronouns used.

First person uses I, me, my, myself and so on; the story is told from inside the narrator’s head and the reader is privy to all the narrator’s thoughts and emotions.

Third person uses he, she, they and so on; the story is told as if there was a camera above the narrator’s head and the reader knows only what the narrator sees. A close third person allows the narrator’s thoughts and emotions to be conveyed to the reader.

Second person is seldom used and talks directly to the reader using you as the main pronoun.

POV techniques include the omniscient POV, which dips into different character’s heads to give the reader a look at the thoughts and emotions of multiple characters; the camera can change from one reader’s head to another, as the story demands.

Point of View as Technique for Getting into a Character’s Head

Point of view, according to Jauss, should be classified by how far into the character’s heads the reader is allowed to go. He proposes a continuum from fully Outside POV, to a POV that is both Outside and Inside and finally a POV that is fully Inside.

Outside, Outside & Inside and Inside. That’s the three new categories of POV. Jauss gives examples of these POV from what we would traditionally call first-person and third-person POV; I’ll be giving examples from the “first-person” book, Ivan, the One and Only. Ivan is undoubtably written in what most would call 1st person POV. The silverback gorilla, Ivan, is narrating the entire story. As such, it has a simple vocabulary and uses simple sentence structure to match the intelligence of an animal; but this animal has a big heart and that’s where technique allows the writer to manipulate how close the reader comes to the character.

OUTSIDE POV: What the Reader Infers about Character

Dramatic. Jauss says, “There is only one point of view that remains outside all of the characters, and that’s the dramatic point of view. . .”

Jauss defines this as a story in which the narrator is telling a story from outside all the characters AND uses language unique to the narrator. Notice that for Jauss, the narrator is an important part of distinguishing the POV technique used.

Dramatic storytelling is the the traditional show-don’t-tell kind of storytelling, where some insist that you must show everything and the reader should understand the action and emotions simply from what is shown.

In the “Bob” chapter of IVAN, we find an example of this, where a small dog interacts with the gorilla:

“He hops onto my chest and licks my chin, checking for leftovers.”

Even though the narrator is Ivan and he is including himself in the action, it is still dramatic action. Nothing in this statement gets inside of Ivan’s head; it’s purely dramatic. In fact, most of the “Bob” chapter is dramatic telling from Ivan’s point of view. He dips into his own feelings (indirect or direct interior dialogue—see discussion later) a few times, but it’s mostly dramatic.

One common demand for a dramatic POV is that the reader understand the character’s emotions only from the actions. If angry, a character might tighten his fists, or his brow might furrow, or he may bare his teeth. Jauss says “the story that results is inevitably subtle. Careless or inexperienced readers will often be confused by stories employing this point of view.” (p. 40)

What a breath of fresh air! Some writing teacher emphasize this Show-Don’t-Tell to the extreme and yet Jauss says the results are “inevitably subtle.” Because I write for kids, I must question whether “subtle” is what I want! I’ve long thought that the Show-Don’t-Tell is more a plea for stronger sensory details than for implied emotion, and have modified it to say, Show-Then-Tell-Sometimes. What I mean is that the sensory details should put the reader into the situation; but after you’ve done that, sometimes you must interpret the actions for the reader.

“Jill slapped Bob, leaving a red palm print on his cheek.”

That uses sensory details; it shows, and doesn’t just tell. But we don’t know WHY Jill slaps Bob. Did she do it to wake him up after he passed out?

“Desperate, Jill slapped Bob, leaving a red palm print on his cheek.”

That word, “desperate,” pulls the sentence out of a strictly dramatic telling and starts to drill down into Jill’s emotions. However, we need that word in order to understand the story.

This technique isn’t used extensively throughout IVAN, but here’s one example. The small elephant, Ruby, is watching the older elephant Stella do her tricks with Snickers the circus dog.

“Ruby clings to her like a shadow. Ruby’s eyes go wide when Snickers jumps on Stella’s back, then leaps onto her head.”

We aren’t TOLD that Ruby is scared of the dog; instead, “Ruby’s eyes go wide.” The reader must infer Ruby’s emotions from that bit of action. And here, it works well. We don’t need an extra adjective for interpretation. Applegate does an amazing job of walking this fine line and keeping the action strictly dramatic.

Dramatic storytelling is like watching a play on stage, or watching a movie. We can never go deeper into a character’s point of view, because the camera can’t go inside a character. The closest we can come is the constant monologues that are a technique of reality TV, where a character talks to the camera and interprets a sequence of actions or explains their thoughts during a sequence. Even that doesn’t take you inside the character like the next techniques can. For the Outside/Inside techniques, join us tomorrow.

This has been part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Outside/Inside: Partially Inside a Character’s Head

October 29, 2013

9 Items to Check on Your Book’s Proof

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

When it’s time to check the proof copy or the Advance Reader Copy (ARC) or the galleys–all those terms refer to a copy of you book that is pre-publication and is one of the last chances to make corrections–take your time. It’s a last chance at perfection.

Here’s a brief look at what you should check:

Proof your Book Cover

Spelling of everything. How many times have you seen a crazy sign that has a misspelling that someone failed to catch? Don’t be that person!

Placement of crucial elements. Do any of the cover art elements interact with the text elements in odd ways? Is anything too close to each other, too close to the spine, too close to the edge?

Promo copy. Have you gotten any new promo copy, new blurbs, new reviews? If anything new has come in since the proof was typeset, this is the time to update any promo copy you can.

Color Reproduction. Probably the cover artist/designer and/or the art director/editor will do most of this. But they will value your input. Speak up if something bothers you.

Proof your Book Interior

New official author photo of Darcy Pattison

Spelling of everything. Ditto from above.

Grammar of everything. Likewise, this is one last chance to prevent the grammar witches from haunting you.

Facts. If there are any factual elements to your story, this is the last chance to check and make corrections. I recently found a wrong date in a book!

Layout and design. Mostly you’ll look for consistency of design. Are the same design elements applied at the beginning of each chapter? Are scene cuts in the middle of a chapter indicated the same way?

Author Biography. Update your author biography one last time, if needed, adding in any new and appropriate promo material. At this point, you can even insert a new author photo, if you like.

Think of the proofing process as your last chance at perfection. If something is less than perfect–speak up. Make changes. Don’t let this opportunity pass without making the changes needed to produce the best book possible.

October 28, 2013

3 Reasons to NaNoWriMo

Now available!

Kindle

Paperback

Are you ready to write 50,000 words in one month flat?

I am.

For the first time, I will be participating in NaNoWriMo, the National Novel Writing Month.

Why this year? Here are 3 good reasons.

Timing. My work schedule has some lag time about now and it’s convenient. That is, I want a new novel done some time next year and by banging out 50,000 words now, I’ll have a rough draft next summer instead of start from scratch. I can’t spend more than a month right now. On the other hand, I do have other projects scheduled and I don’t have more than a month to spend on a new project. And I want to maximize my time and effort. Pouring out a full draft in a month sounds exciting.Because this is going to work really well (do you hear my optimism?), I will also be in better shape next year, when I have time to return to this story. I’ll have a draft, and revisions will be faster for the work done this year.

Trust the process. Learning to trust the process must be a life-long project for writers. Because this writer is having to do that over and over this year. So, instead of fighting the process, I’ve decided to embrace the writing process for the month of November.

Taking creative risks. Writing a novel is always a risk. In novel revision retreats, I have people walk around and congratulate each other on writing a full draft of a novel. It’s an amazing accomplishment. Each time I start a new novel, I am very aware of the risk, that this novel may be one that lands in a file drawer, or that I will abandon it and not finish. And yet, to be creative means to take risks, to reach for something new and different, and to go where “no one has gone before.” If I’m not taking risks in my work, then I’m going nowhere. But risks are scary and uncomfortable. NaNoWriMo is a contained risk: I only have to write 50,000 words and it’s only for a month. It’s risky, sure. But there’s support, others to follow, inspiration and there’s a definite end to it. I am very glad there will be an end to the month of NaNoWriMo.

Of course, getting ready for this, I’ve been reviewing my book, START YOUR NOVEL. I need to take my own advice!

Are you NaNoWriMoing? (How’s that for turning an acronym into a verb?)

Any words of encouragement for me?