Darcy Pattison's Blog, page 17

November 14, 2014

How to Choreograph a Great Action Scene

NOW AVAILABLE! 30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Paperback Book Available now.

Video Course Available now.

Kindle PreOrder Now

Kobo ebook PreOrder Now

I recently found a gem of a writing book. For my NaNoWriMo challenge, my current love/hate WIP, I decided I wanted to include more action scenes, pushing it more toward YA and more toward a true action book. OK. Action. That should be easy. Um. No.

Until I read this book. Ian Thomas Healy breaks down action into manageable chunks in his book, Action! Writing Better Action Using Cinematic Techniques.

Until I read this book. Ian Thomas Healy breaks down action into manageable chunks in his book, Action! Writing Better Action Using Cinematic Techniques.

The title appealed to me right away because I do like action/thriller movies, and I recognize that writing action means you must fully evoke the visual, auditory and kinesthetic senses, like a movie would be able to do. Healy delivers.

Action Scenes = Violence

The first shocking thing to realize is that action means violence, says Healy. It’s not just movement, but conflict made concrete. Movement across a scene without a purpose is just the beat of a scene and action implies much more.

Healy breaks down action scenes into three levels: stunts, sequences and engagements.

1) On the simplest level, a STUNT is a single brief action. Carver pulls a gun and fires.

2) ENGAGEMENTS moves up a level by combining multiple stunts as a character moves across a setting. Now, you’re talking more choreography and relating the characters to the setting. Actions are physical, not mental, and thus, they require a setting. How the characters move across the setting while doing stunts is an Engagement. They end with the resolution of a plot point, or they transition into another Engagement, perhaps going from a chase to a fight.

3) A SEQUENCE is a combination of Engagements related in some way. Maybe they are about the same character, setting or conflict.

What actions are possible in this setting? What violence is possible here?

This is immensely helpful and practical! When I approach an action scene, first I make sure I understand the setting. What is present in the scene physically and how will that affect the story I can tell. Is there a river? Then some possible stunts would be diving into the river, wading, falling in, slipping on a muddy bank, fist-fight in the water, crossing the river, swimming, fist-fight while in water, and so on. I’m not just trying to create stunts on the fly, but the setting itself suggest what is possible. What if I want the character to fly away? Then the setting must be a unicorn stable, or an airstrip. Can I get the characters to the right place for this scene?After listing what’s possible in this scene, I can start to map out the action. Often, this is just a mental map, but I can also fall back on a paper/pencil map when needed. Draw out the setting. Put an X where the characters are standing. Then Write #1, 2, 3 and so on for where they move to across the landscape to create an Engagement. Physically point–put your finger on the spot where the actions starts. Move your finger to the next spot where a stunt occurs. Sounds mechanical? Yes! But it works, and that’s the point. As I get better at this, maybe I’ll be able to do it all mentally. But for now, this is working great.

Finally, combining the Engagements into Sequences is simple.

There’s so much more in Healy’s book to recommend. Consider this provocative statement: “One of the most useful things you can do with an Engagement is use it to strengthen character relationships.”

If you’re writing or considering writing a book with lots of action, this is a great tutorial. On his website, Healy critiques some action scenes–interesting to see what he focuses on in the critiques!

One last thing. Yesterday, I was trying to write an action scene set in Mt. Rainier’s National Park and nothing was working. Then, I realized that was because I didn’t know the setting well enough! Of course, if action scenes move across the landscape, then I needed to know my landscape better. I spent the day studying Google Earth, watching You-Tube videos, scanning lists of flora/fauna, and hunting for autumn photos of the stunning vine maple. Before you can write about a physical space, you must know something about it!

November 12, 2014

Online Video Course: 30 DAYS TO A STRONGER NOVEL

NOW AVAILABLE! 30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Paperback Book Available now.

Video Course Available now.

Kindle PreOrder Now

Kobo ebook PreOrder Now

The course is now live on Udemy.com!

Each day includes:

A quote that inspires

Short, practical instruction from Darcy on a specific topic

A simple “Walk the Talk” action to take

Over the course of the month, you’ll receive the entire text of Darcy’s book, 30 Days to a Stronger Novel (November, 2014 release).

Over the course of the month, you’ll receive the entire text of Darcy’s book, 30 Days to a Stronger Novel (November, 2014 release).

We can’t guarantee that you’ll end the month with a publishable novel; but we can guarantee it will be a STRONGER novel.

We can’t guarantee a publishable novel; but we can guarantee a STRONGER NOVEL!

Sign up now and receive $5 discount. Use this code: 5OFF30Days

Sign up now and receive $5 discount. Use this code: 5OFF30DaysVIDEO COURSE TABLE OF CONTENTS

Watership Down with Armadillos: Titles

Search Me: Subtitles

Defeat Interruptions: Chapter Divisions

Scarlett or Pansy: The Right Character Name

My Wound is Geography: Stronger Settings

Horse Manure: Stronger Setting Details

Weaklings: Every Character Must Matter

Take Your Character’s Pulse

Yin-Yang: Connecting Emotional and Narrative Arcs

Owls and Foreigners: Unique Character Dialogue

Sneaky Shoes: Inner and Outer Character Qualities

Friends or Enemies: Consistent Character Relationships

Set Up the Ending: Begin at the Beginning

Bang, Bang! Ouch! Scene Cuts

Go Away! Take a Break

Power Abs for Novels

White Rocks Lead Me Home: Epiphanies

The Final Showdown

One Year Later: Tie up Loose Ends

Great Deeds: Find Your Theme

The Wide, Bright Lands: Theme Affects Setting

Raccoons, Owls, and Billy Goats: Theme Affects Characters

Side Trips: Choosing Subplots

Of Parties, Solos, and Friendships: Knitting Subplots Together

Feedback: Types of Critiquers

Feedback: What You Need from Readers

Stay the Course

Please Yourself First

The Best Job I Know to Do

Live. Read. Write.

Discount Code

Sign up now and receive $5 discount. Use this code: 5OFF30Days

November 11, 2014

The Power of One

NOW AVAILABLE! 30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Paperback Book Available now.

Video Course Available now.

Kindle PreOrder Now

Kobo ebook PreOrder Now

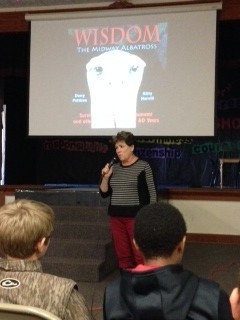

I did a school visit on Friday in the tiny town–only about 700 population–of Gillett, Arkansas. The Elementary School and Early Childhood Center are still located in Gillett, but the district was merged with DeWitt, Arkansas, and all middle school and high schools are located in Dewitt, about twenty miles away.

I came at the request of Joli, the PTA President.

Young, beautiful, and full of passion for her community, Joli Holzhauer is a living testament of the Power of One.

The city’s claim to fame is the annual Coon Supper, an event that no politician in Arkansas will miss. Bill Clinton attended the event for many years and brought with him the major political forces; this year, almost every candidate for major offices in Arkansas attended. The event often gets CNN or FoxNews coverage.

Wikipedia adds: “The largest alligator ever killed in Arkansas was harpooned near Gillett on September 19, 2010. The thirteen-foot one-inch reptile weighed 680 pounds.”

Joli met her husband, the current mayor of Gillett, at Mississippi State University, when he was planning a far different career; instead, he came home to farm. The area has cotton, soybeans, rice, corn and other crops which grow in this fertile, flat delta area. She says it was different at first from what she was used to, but she dug in and started working to support her community.

Rachel Mitchell, the principal of Gillett Elementary said that Joli comes in to chat and asks, “What do you need? What do you want?”

And then, Joli makes it happen. The PTA sold chocolate bars. Now, in a community of only 700 people (that includes children), how many chocolate bars can you sell? $3000 worth. Whatever the school needs or wants, one person is making a difference.

Intelligent, smart, committed. Small communities and their school survive because of people like Joli. I salute you!

November 3, 2014

6 Questions to Sharpen Your Story Beats and Make Your Plot Sing

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Sign up for EARLY BIRD list for discounts

The book is now available for Pre-Order! It officially goes on sale on November 14.

When you’re writing or plotting a story, one way to approach it is to write out the story beats. A beat is a small action; a collection of beats makes up a scene. It’s sort of like choreographing a dance; you must make character move around, interact and do things. You can write story beats on the fly if you like, but I like doing some planning ahead so the actual writing is easier. If you, too, write story beats ahead, here are some things you should keep in mind.

Where are the characters in space? Because beats represent physical actions of a scene, you must always keep in mind where the characters are in space. In a dining room, is mother on the other side of the table from her daughter or on the same side. If she’s on the other side, then she can’t reach out and touch her daughter. She must physically walk around the table to do that. You must always be aware of EXACTLY where each character is. Draw it out or act it out if necessary.

Where are we? The story’s setting determines the types of action possible. Moving around a marina is very different than running through a wooded area. Photo by Darcy Pattison.

What is the moment before? When a scene opens, don’t have a character move out of empty space. For example, if you write, “Mom walked over to Lucy,” then I want to know where Mom started that walk. Where was she the moment before this started. Place her somewhere and give the reader enough context for the action to make sense.

Can you name and transform an emotion? To help me write a scene, sometimes I need to actually name the emotional back and forth. Then, I work to push the emotion into the dialogue, the beats (actions) or the body language. If mother wants to appeal to her daughter for understanding, perhaps she pulls out a chair and sits, which puts her in a lower position than the daughter. If she holds up her hands, mother becomes a supplicant before the daughter and the beats/body language reinforce that mother is asking for understanding. Then, you don’t have to say it, because you’ve shown it. But naming it helps me keep the emotional tensions as tight as possible.

Can you escalate the tension? Mother grabs the daughter’s arm. That’s definitely conflict. But when Mom squeezes harder, the tension escalates. Within a scene you want a mini conflict that rises to a small climax and you should be using the beats to help you escalate and build that tension. What beat did you list? How can you escalate that action in some way? Mom squeezes harder; mom’s face gets in daughter’s face; one of them shoves the other; and so on.

What body Language would help express the beats? While you are writing out the beats, or the actions that characters take, it could be subtle changes of body language. One character leans closer to hear better. Another crosses arms over her chest to fend off a verbal attack. Avoid the clichés: looking away, spun away, tears rolled down her cheeks. Instead, look for fresh beats and fresh ways to use body language.

Is the action clear? Above all, you must strive for clarity. Readers must never be confused about what is happening in a scene. Try to look at it with fresh eyes and see it as a first-time reader would see it. Clarity trumps pretty language every time.

October 27, 2014

Authors as Speakers: Inspiration from TED

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Sign up for EARLY BIRD list for discounts

The book is now available for Pre-Order! It officially goes on sale on November 14.

Do you speak for organization as a way to advertise your books? Maybe you do school visits, or talk to a Kiwanis club, or even do Keynote Speeches for various organizations as a way to supplement your writing income.

If so, I’ve got a great book for you.

TED Talks

I am inspired by the TED Talks. TED, or Technology, Entertainment and Design, a nonprofit organization, invites people to give “the speech of their lives” in 18 minutes or less. Each speech should focus on one “idea worth sharing.”

The video archive includes some of the best public speaking you’ll ever see.

If you want to give better speeches, it makes sense to study the TED talks.

And that’s exactly what Jeremey Donovan has done in his book, HOW TO DELIVER A TED TALK: SECRETS OF THE WORLD’S MOST INSPIRING PRESENTATIONS. As you read this post on October 27, 2014, I’ll be at a Reading Recovery conference speaking about my work. The last time I went out, I bombed.

And that’s exactly what Jeremey Donovan has done in his book, HOW TO DELIVER A TED TALK: SECRETS OF THE WORLD’S MOST INSPIRING PRESENTATIONS. As you read this post on October 27, 2014, I’ll be at a Reading Recovery conference speaking about my work. The last time I went out, I bombed.

Now, I do a lot of speaking and it comes pretty easy for me. But last time, I really wasn’t prepared the way I should’ve been, and it showed. I vowed THAT would never happen again. In fact, that failure has spurred me to aspire to do better than ever before. Whatever level I was before, I’d like to up the game and improve.

Focus. When I taught freshman composition, the hardest thing was to get students to focus on something important enough, but manageable within the five pages of the assignment. Focus is difficult because we have so much we want to say. But not everything needs to go into THIS speech. TED talks ask you to find that one “idea worth spreading.”

It took me a long time to focus this speech! In some ways, the question is a philosophical one: what do you care about passionately? That’s what will connect with people.

Structure. Like any good writer or speechwriter, Donovan spends a lot of time on organization. There’s nothing particularly new or innovative in this section; however, his analysis of speech after speech is helpful, because you’ll see exactly how other TED talks were organized. He covers both inductive and deductive reasoning in detail.

Storytelling. The use of stories to enliven a speech is a time-tested technique. But Donovan explains the WHY and WHICH ONE. For me, the emphasis on a personal story was important. I am an ambivert, able to be extroverted when necessary, but in my everyday life, I’m an introvert. I don’t like sharing personal stories. And yet, for others to connect with you, it’s necessary. My new speech includes several new personal stories.

Powerpoint. Donovan says that about 60% of TED talks have no Powerpoint. Hurrah! It’s not my favorite method of giving information to a crowd. However–this time, I realized that I needed to do one. My normal approach would be to blow it off till the last minute–but that didn’t work last time and I was determined to do it right this time. I created a 55 slide pack.

Practice. Really? You want me to practice this 70 minute presentation? Yes. If I was doing a TED talk–with all the prestige of that organization, you can bet I would practice. I’m planning to do a run through a couple times this weekend. Realistically–one really good run-through is likely, but that’s better than the last time!

The benefits of taking the time to focus on the speech should be great. I know that I’ll relax more because I’m prepared. The connection with the audience should be much better than last time when I truly bombed. And who knows where it will go from there.

Slideshare From Jeremey Donovan

How to Deliver a TED Talk I 10 Insights from Jeremey Donovan from 33voices.com

You should watch a 100 of these videos before you go out to do your next presentation! Here are some TED Talk Playlists to get you started.

As you read this, I’ll be about to speak. So send me the traditional on-stage blessing: Break a Leg!

October 20, 2014

Why I LOVE Cliches and Tropes

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Sign up for EARLY BIRD list for discounts

The book is now available for Pre-Order! It officially goes on sale on November 14.

I confess: I love a good cliche or trope.

A cliche is a phrase or expression that has been used so often that it is no longer original or interesting.

A trope is a common or overused theme or device, as in the usual horror movie tropes.

I’m in the middle of plotting a massive 3-book story and I need all the help I can get. Here’s the problem: what happens next?

No, let me rephrase: what could possibly happen next?

Sometimes, I just need to know possibilities, or what a story typically does at a particular stage. What are the possibilities? Is this a place for a murder, a confession, a love scene, or a time to gather information?

Literary folk say that there are only a limited number of stories in the world. Depending on who you talk with, there might be just two stories: a character leaves town, or a stranger comes to town. Others say there are up to 32 plots. I’ve written about 29 plot templates before. And it helps immensely to narrow down the choices.

But that’s on the level of an outline. Now that I’m deep into deciding on scenes, my imagination comes up short.

Enter tropes. A trope is a common theme, something that’s been done before. That doesn’t scare me away, because it’s the same as the variety of themes. Every story is a cliche, trope or template in many ways. It’s all in how you TELL that story. The beauty is in the particulars.

Romantic Subplot

My story needs a romantic subplot. I know the basics.

Act 1: Boy Meets Girl/Girl Meets Boy

Act 2: Boy and Girl Fight or are otherwise kept apart.

Act 3: Boy and Girl get together.

But what else? What is possible at each stage?

I turned to TVTROPES.org for help. Their site is a wiki that list all sorts of tropes. The Romantic Arc Tropes list was helpful because it listed typical things that happen at every stage of a romantic relationship.

For example, a story might start with this trope/subtropes:

Love Before First Sight

Because Destiny Says So

Childhood Marriage Promise

Red String of Fate

Girl of My Dreams

New Old Flame

Each of the tropes listed has its own wiki page, which explains the trope in detail. Particularly valuable are the examples drawn from traditional literature, manga, comic books, fanfics, films, live-action TV, professional wrestling, table top games, theater, video games, webcomics, western animation, real life and more. It’s a treasure trove of examples of the POSSIBILITIES of a particular stage of a relationship.

In fact, I used this romance arc by choosing one trope from each stage of a relationship and slotting that into my story.

Place Holders

Are you afraid that my story will be trite and boring? I’m not. I know that this is a trope and therefore, I must transform it in the storytelling phase of the project. Right now, though, this trope acts as a place holder, something that indicates approximately what will happen in this spot of the story, but not exactly. The nuances that make it fresh await the actual writing.

Using tropes to hold a place with something reasonable makes the plotting easier. I’m loving this help in plotting.

Here are some Arcs to get you started. Be warned: this is a massive wiki and it’s easy to get lost in it. Know what you are looking for and get it/get out.

Romantic Arc Tropes

Mystery Arc

Rescue Arc

War Arc

October 14, 2014

10 Writer Quotes to Keep you Working on Your Novel

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Sign up for EARLY BIRD list for discounts

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video course

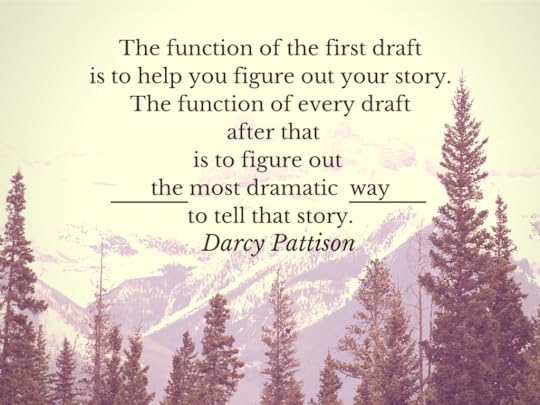

Writing teacher Darcy Pattison teachers an online video course, 30 Days to a Stronger Novel. Each day includes an inspirational quote, and tips and techniques for revising your novel. Here are the 10 of the inspirational quotes.

LEARN MORE: ONLINE VIDEO COURSE.

Or sign up for more information on the availability of this course and other courses.

The titles below are the first ten entries of the Table of Contents for the Online Video Class. Sign up now for the Early Bird list. You’ll be notified when the course goes live.

Mims: Online Video Course

Sign up for information on online video courses with Darcy Pattison. Discounts, deadlines, and more.

Email*NameFirstLastOnline Video Courses*30 Days to a Stronger Novel

The Wide, Bright Lands: Theme Affects Setting

Raccoons, Owls, and Billy Goats: Theme Affects Characters

Of Parties, Solos, and Friendships: Knitting Subplots Together

October 13, 2014

3 Ways to Know If Your YA Fiction Is Really New Adult Fiction

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Sign up for EARLY BIRD list for discounts

In the immortal words of Charlotte in E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, “It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer.”

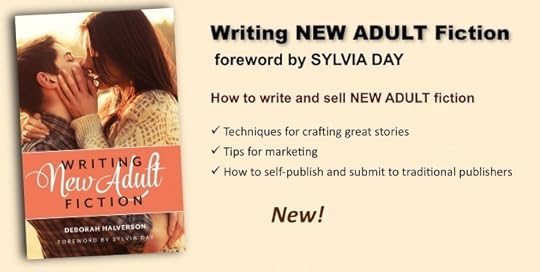

I was privileged to have Deborah Halverson edit my Harcourt picture book, Searching for Oliver K. Woodman. When we met at a retreat, it was instant friendship, and anytime we talk, it feels like we’ve been friends forever. That’s why I am so excited about this new book. Well, I’m excited because it’s Deborah’s book, but also because it’s the first book I’ve seen to explain the latest fiction genre, New Adult. In Deborah’s capable hands, the topic comes alive and I’ve already got tons of ideas for stories. Here, she answers a basic question; but if you want more, you’ve got to buy her book!

Guest post by Deborah Halverson

YA writers often ask me to explain the difference between Young Adult fiction and New Adult fiction when the story’s main character is 18 or 19 years old. Some of those writers are curious about this new fiction category that brushes up against their own, but others are trying to noodle out whether that upper YA story they’re working on is really NA. “Tell me what NA is, Deborah, and then I’ll know what I’ve got.” Happy to help! Here are three ways to determine if you’re writing a story about a young adult or a new adult.

DearEditor.com Deborah Halverson is doing a special giveaway for the blog tour for the kickoff of this book. Enter to win “One Free Full Manuscript Edit!“

Pin Down Your Protagonist’s Mind-set

How does your character process the world and her place in it? Teens are typically starting to look outward as they try to find their places in the world and realize that their actions have consequences in the grander scheme of life, and they yearn to live unfettered by the rules, structure, and identities that have defined their lives until now. New adults finally get to live that free life they dreamed of—for better or worse. They move forward with the self-exploration they began in their adolescence, going big on personal exploration and experimentation and expanding their worldview. They get to build identities that reflect who they’ve become rather than who they grew up with, and they get to try things out before settling into a final Life Plan. All of this can be overwhelming even when it goes well—after all, even good change is stressful, and “change” is new adulthood in a nutshell. For some, though, the instability is a total freak-out. The clash of ideal vs. reality can shock their system. They’re gaining experience and wisdom hand over fist, but yikes. Luckily, new adults tend to brim with personal optimism, and their explorations and experimentations—both dangerous and beneficial—are endearingly earnest.

If this sounds like your protagonist and her circle of friends, you might have an NA on your hands. You can use this knowledge to give your story a solidly NA sensibility by exposing your character’s inexperience in her decision-making, by imbuing the narrative with a sense of defiance, by conveying stress, by conveying self-focus (not selfishness), by lacing the exposition with personal optimism, and by showing the character’s awareness of her growing maturity. YA characters who are overly analytical about themselves and others risk sounding too mature, but NA character journeys ooze with self-assessment no matter the individual details of their journeys.

Assess Your Circumstances

In fiction, the plot exists to push the protagonist through some kind of personal growth. Thus, our character’s mind-set and the plot are interdependent. Whether your character is a young adult or new adult, the circumstances of your story—the events, problems, places, and roles—should sync with that character. New adults tackle their problems with their new adult filters in place, whether the story is a contemporary one set in college, or a historical one, or a fantastical one. Self-actualization is an essential growth process whether you’re at a college kegger or battling evil overlords.

In fiction, the plot exists to push the protagonist through some kind of personal growth. Thus, our character’s mind-set and the plot are interdependent. Whether your character is a young adult or new adult, the circumstances of your story—the events, problems, places, and roles—should sync with that character. New adults tackle their problems with their new adult filters in place, whether the story is a contemporary one set in college, or a historical one, or a fantastical one. Self-actualization is an essential growth process whether you’re at a college kegger or battling evil overlords.

Once you’ve pinpointed whether your protagonist’s mindset feels YA or NA, consider if your plot events and the circumstances of your protagonist’s life jive with her concerns, fears, coping skills, maturity, and wisdom level. NA story lines tend to remove structure and accountability, tweak the characters’ stress levels by playing musical careers and homes, make money an issue, force the characters to establish new social circles at play and at work, show characters exhibiting ambivalence to adult responsibilities, show characters divorcing from teenhood, show characters striving to “move on from trauma” rather than to “survive trauma”, deny the characters the “ideal” NA life of carefree self-indulgence, put characters in situations that clash their high expectations for independent life against a harsh reality, and show the process of evaluation, of trial-and-error, of weighing exploration and experimentation against consequences, at least by the end of the story.

Deal with the “Sexed-Up YA” Thing

Romance is part of almost any older YA story, and certainly all NA. As it should be—romance is one of the three main areas of identity exploration after puberty, along with career and worldview (think politics, faith, and personal well-being and outlook). The difference is that teens are very solidly in the “what is love, what does it feel like?” realm, whereas new adults are generally working on who they want to be in a relationship, what they want from their partner, what they want from the relationship in general. That doesn’t mean they’re actively searching for Mr./Mrs. Right—there’s plenty of time for that!—but it does mean they want a satisfying, meaningful relationship. Where is your character on that romance spectrum?

Of course, romance isn’t really what people focus on when comparing YA and NA relationships, is it? Nope: it’s sex. So let’s talk about sex. In its early days, NA was accused of being “sexed-up YA”, but after reviewing numbers 1 and 2 above, you’ll see that the differences between YA and NA are more substantial than simply how explicitly you describe two bodies connecting sans clothing. Ask yourself your goal with the romance, and what level of sexual detail is necessary for that goal. Then consider your audience: NA readers are mostly adults of the same 20- to 44-year-old “crossover reader” demographic that shot YA into the publishing stratosphere. (A Digital Book World study reported 2013’s dominant YA crossover readership as being 20- to 29-year-olds; compare that to the 18- to 25-year-old age range of new adulthood). Those grownups can handle—and often flat-out want—explicit sex scenes. Some teens will read NA, but mostly they’re not into that mind-set yet so the stories don’t resonate with them, making them plenty happy to stick with the many great YA stories out there that reflect their current time in life.

Perhaps you determine that your character’s mind-set and story circumstances are solidly YA but you want/need to include some sex scenes in your story because the theme or plot of the story calls for it. In that case, maybe you have a solid YA that requires a “Mature YA” categorization to let readers know that there’s sexual content between those covers. Those scenes will be tamer than the full-on explicitness of NA—your are writing/positioning this story primarily for and about young readers after all, and there are gatekeepers involved—but the sexual content is there and readers are warned. Weigh your goals with your romance, your story’s scene needs, and your audience’s expectations and sensibilities as you make the NA/YA determination on this aspect of your WIP.

So there you have it. Three ways to know if that story you’re writing is Young Adult fiction or New Adult fiction. Good luck with your WIP, and with all your publishing endeavors.

Deborah Halverson is a veteran editor and the award-winning author of Writing Young Adult Fiction For Dummies. Her latest book, Writing New Adult Fiction, teaches techniques and strategies for crafting the new adult mindset and experience into riveting NA fiction. Deborah was an editor at Harcourt Children’s Books for ten years and is now a freelance editor, the founder of the popular writers’ advice website DearEditor.com, and the author of numerous books for young readers, including the teen novels Honk If You Hate Me and Big Mouth with Delacorte/Random House. For more about Deborah, visit DeborahHalverson.com or DearEditor.com.

Deborah Halverson is a veteran editor and the award-winning author of Writing Young Adult Fiction For Dummies. Her latest book, Writing New Adult Fiction, teaches techniques and strategies for crafting the new adult mindset and experience into riveting NA fiction. Deborah was an editor at Harcourt Children’s Books for ten years and is now a freelance editor, the founder of the popular writers’ advice website DearEditor.com, and the author of numerous books for young readers, including the teen novels Honk If You Hate Me and Big Mouth with Delacorte/Random House. For more about Deborah, visit DeborahHalverson.com or DearEditor.com.

October 7, 2014

Subplots Fight Writer’s Block

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Sign up for EARLY BIRD list for discounts

Subplots are a connected sequence of events, just like any other plot; the difference is that this is a minor plot with fewer developments. It should affect the main plot in some important way–or else you should delete it–but it doesn’t need the same development of a main plot.

Subplots are a connected sequence of events, just like any other plot; the difference is that this is a minor plot with fewer developments. It should affect the main plot in some important way–or else you should delete it–but it doesn’t need the same development of a main plot.

I am still plotting my trilogy, and I’m taking a different strategy this time. I am working on the plot line for the entire trilogy before I start writing. Each book focuses on a different aspect of the overall story problem, so in some respects, each book is a subplot. Yet, overall, the story needs a throughline, or a question that overshadows everything.

In my sff trilogy, the overriding question is will the Risonian planet blow up, killing all Risonians? Or, will they find a new home and refuge?

The subplots will focus on different characters in the story and how they answer different parts of the overall problem. There are three romance subplots, various political subplots, and a couple survival subplots. Characters are motivated by revenge, by a quest of power, or by a sense of desperation.

That’s all good! In a long story–such as a series or even just a trilogy–the story needs to have some depth and breadth, and subplots have the potential to help.

As I say in START YOUR NOVEL, it helps to look over 29 different plot templates and decide on the overall plot for your story. Clearly, my story is about survival, and I can echo that with other smaller stories or subplots of survival. I can also contrast with someone who is out for revenge and cares nothing for survival; revenge at all costs makes for desperate–and potentially compelling–drama. Romance plots: OK, these should be a given in most stories, even if it’s just a love story between a boy and his dog.

What Happens Next?

It often happens that I am trying to work out the main plot but get stumped. What happens next? I’ve no idea.

Then, it’s time to turn to the subplot that has been patiently awaiting notice. What happens next in the subplot? Part of getting stuck is the fear that if I make a major decision about the trajectory of the story, I’m stuck with it. If it’s wrong, it will mean a major revision. Subplots, though, are small and contain fewer scenes. Make a mistake there and it’s much easier to revise later. By focusing on a smaller problem, you put less at risk.

Sometimes I have to go down the list and answer the “What next?” question for each subplot before I get inspiration for a better setting, more compelling emotions, or a larger conflict.

Often, figuring out the next logical step for a minor plot shakes loose a detail that will make everything connect better. Oh! So, she’s the main character’ sister, and that’s why she wants revenge.

The new revelation sends me back to the main plot with a new twist on the action.

When I’m really stuck, I repeat this process with every subplot from action to romance. For example, a romance subplot implies that tension and conflict permeates the man-woman relationship. How does the betrayal, the attraction, the hate, the love, and the self-sacrifice relate to and affect the main plot?

Progress is slow on this huge plot. Thanks to subplots, though, it is progressing! What happens next? My story gets plotted!

September 29, 2014

Do You Write for the Market? Or Yourself? Or Both?

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

Sign up for EARLY BIRD list for discounts

Do you write for the market? Or do you just write novels, picture books and articles for yourself?

You’ll hear the advice both ways:

Write what you want to write so you can write the truest book you can write.

Write with the market in mind.

It depends on your writing goals.

If your writing is self-expression and you have other means of monetary support, then please yourself!

If your goal is a career as a writer, and becoming a writer who makes a living wage, then the answer is more nuanced. It’s not just write for the market; you must write what you want to write. But you must also find your audience.

Writers who have a long career seldom start off with a bang. (I once went to a conference where every speaker had sold his/her first book to the first editor who saw it. I went home and cried.) Instead, it’s a slow build of an audience who comes to your work one at a time. This means your writing is improving while your audience is growing.

However, this doesn’t give you the pass on considering the market and your audience.

Consider Your Audience

What is your audience reading? What is popular? That’s often the question that writers ask themselves and it’s a valuable one. Knowing the current market is vital. But you must go deeper and ask, “Why is my audience reading this type of book?”

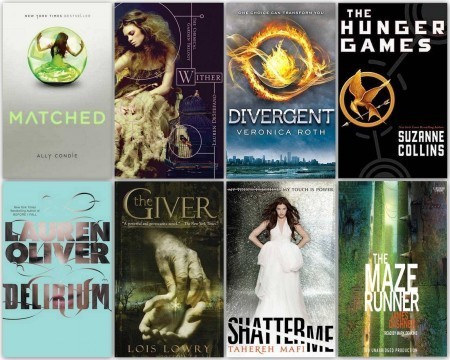

For YA literature, for example, dystopian literature has been wildly popular for the last five years or so. Why? Because in times of upheaval, people reexamine their identity and challenge the very foundations of civilization–which is exactly the task every generation faces as they come to adulthood. Who are they? What will their life be like?

Are dystopian novels dead? Click on the image for an interesting take on how the genre is overrun with cliches from uzerfriendly.com

Perhaps a simplistic reason, but the idea here is to look under the surface of what is popular to find the reason for the popularity. Once you know the deeper reason, then address THAT in your next book. And do it in a new, fresh, exciting way.

When I approach an editor’s revision letter, I do the same thing. I don’t do every thing the editor asks for. Instead, I look for the deeper, perhaps unspoken concerns, and address those. Editors don’t need to be right; they just need to provoke you to move from your stubborn position and do something even more wonderful than they ever imagined. That’s what I’m asking you to do here. Look at trends in the marketplace–and transcend them. Find a way to answer the deeper concerns in a way that only YOU could do.