Darcy Pattison's Blog, page 11

October 19, 2015

Go, Indie! Young Writer Go, Indie!

On July 13, 1865, Horace Greeley penned an editorial that is famously quoted: “Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.”

I had the privilege of meeting with a young writer this week who wanted to chat about her future. She’s articulate, smart and engaged. She’s already a member of a fan-fiction forum where she chats with other teens about writing. She’s planning to take the NaNoWriMo challenge and write 50,000 words in November. Even at fourteen, with parental controls carefully in place, she’s linked in and excited about the future of book publishing. Here are some of the things we discussed.

Go Indie, Young Writer, Go Indie, and Grow Up with the Industry.

Write 10,000 hours. If you want to be a writer, you must write.

I asked Young Writer, “How many hours do you need to write to become a great storyteller?”

She said, “My preacher said 10,000 hours to be good at anything.”

Obviously, someone has read Malcom Gladwell’s book, Outliers, where he claims experts need that level of commitment. Whether you believe that number or not, it’s true that writers write. They don’t talk about writing, they don’t study text books about writing, they don’t wish they had written. They write.

Likewise, most writers who are successful are readers. It’s certainly possible to avoid a deep literary background of reading–but I believe it’s much harder. Pour language in to get language out. The wider the variety of reading, the better.

Prepare to be a social media maven. A second skill for writers growing up today is social media. Aspiring young writers should become comfortable on different social media platforms and participate a variety of communities devoted to literature. One thing that definitely means is the young writer needs skills in photo editing. Taking your own photos is even better, but for sure, they should be able to edit photos. For example, Facebook needs horizontal photos, while Instagram prefers square, and Pinterest highlights vertical. Can you take one photo and format it to fit each platform. Even as platforms morph (Instagram now allows horizontal or vertical, while preferring square), the ability to reformat photos will remain a valuable skill. One step farther, video skills will become increasingly important online. These are things that even a fourteen-year old can do, before they are even allowed by cautious parents (Hurrah for cautious parents!) allow social media accounts. For example, Lynda.com offers reasonably priced video tutorials on a wide variety of skills, including photo editing.

Prepare to be a small business person. Already, Young Writer was asking, “Should I go Indie?”

When I said, “Yes,” she was excited. She was already tending to think indie was a strong option for her.

And fourteen years old is the time to think Indie, because it requires an entrepreneurial mindset. Indie authors are small business persons. They need a variety of skills: accounting, marketing, graphic design for book covers and book layout, social promotion and more. This was perhaps the biggest surprise for the Young Writer’s Mom. She had thought only of writing and producing the books, not of marketing them.

Now is the time to think about the classes to take in high school and college that can feed into a successful venture in indie publishing. Learn accounting and financial management. One of the biggest challenges for me has been the financial side of indie publishing; in fact, I’d never even taken a basic accounting class before I started my venture. I suggested that Young Writer invest time in accounting, accounting software, and thinking like a financial planner.

Likewise, books are an exercise in graphic design. Whether you do ebooks or print books, the book cover is a crucial sales tool, and the interior must be laid out in a professional and pleasing way. I’m not saying that Young Writer must do all her own graphic design; rather, she must be comfortable acting as an art director for her books. That means some experience in a graphic design class will help her see possible difficulties and solutions and hopefully, give her an eye for great design. Maybe an arts appreciation class is just as important as the graphics design class.

What should I major in in college? asked Young Writer.

The answer depends on Young Writer’s goals. Indie authors create multiple income streams to survive, especially in the early years. Typically, a writer earns income from book sales, speaking engagements, and teaching. Throw in some extra sales from repackaging the book for different formats: paperback, hardcover, ebooks, audiobooks, online video courses, and so on.

If Young Writer wants to be a creative writing professor at a university level, then an MFA in Creative Writing makes sense. Or even a Ph.D. University programs are generally great at turning out professors, and not necessarily (with exceptions, of course) turning out practicing and successful writers.

However, if Young Writer wants to really go entrepreneurial and try to make a living from her writing, I’d advise a minor in Creative Writing (while working on her 10,000 hours experience), and a degree in something else. Michael Crichton, author of Jurassic Park and other classics, graduated from medical school, although he never practiced as a doctor. The expertise in medicine–and his comfort in dealing with technical issues from chemistry to anatomy–brought something unique to his fiction. He was comfortable discussing the genetics of bringing back extinct species of dinosaurs – and making the science fiction plausible. Likewise, Young Writer might benefit from a degree in history, archeology, sociology, anthropology, medicine and so on.

It depends on Young Writer’s goals, their personality, and their commitment to writing. But now is the time to think about options. And I think the future for smart young writers is in their own hands. Go Indie, young writer, go Indie, and grow up with the industry.

October 5, 2015

The Heart of Revision: Finding Your Own Answers

I’ve written before about revising based on critiques and editorial letters covering both the emotional upheaval and the how-tos.

Revise Second Draft: 419 Specific Comments

Do you get MAD at Editors? I Do

Don’t Follow That Revision Letter: Here’s Why

To Revise or Not to Revise: Who are you revising for?

DECISIONS: What and How to Revise

I Don’t Want an Honest Critique

You’d think I’d know what I’m doing by now.

But each revision brings challenges. I’ve been struggling through the line edits on my manuscript and I’ve found them to be of three general types:

Clarity. My original wording is unclear. The line edit added clarity. These, I keep or modify even further to make sure I’m clear. Writing is the act of putting something on paper that reproduces a thought EXACTLY in the reader’s mind. That’s makes clarity the first goal of all writing. Otherwise, the communication fails.

Technical issues. This might include subject-verb agreement, verb tense, etc. I’ll almost always do this.

Matters of choice. Some edits however, just seem to be a matter of personal preference. Which way would you say this?

It was like a dolphin’s tail.

It was akin to a dolphin’s tail.

Both versions are clear; there are no technical issues. On line edits like this, I do what I want. Or more specifically, I look at the surrounding text and ask myself, “Would I write that? Is that my voice?”

I won’t accept any line edits that change my voice or try to force it into other paths. I’m not foolish: I consider the edit because maybe I was lazy when I wrote this paragraph and I wasn’t thinking of the best choices. Often, however, it’s how the editor would have phrased it and it’s not my voice. No go. I won’t change that.

Line edits, then, take time. You must consider each one in turn and decide to keep it, modify it even more, or reject it.

And that’s the problem right now. I’m bogged down in line edits. Talking with a friend, she said it a different way: you need to re-read the editorial letter at different points in the revision.

Editorial letter. Oh, yeah. That. There is a long editorial letter that addresses overall issues of plot, characterization, pacing, and backstory. THAT is what I really wanted to focus on for this revision. Instead, I’m just tediously going through line edits.

Revision is a combination of micro and macro. You must go deep into the words and sentences used to tell the story–the line editing. But at the same time, you must pull back and take a wider view. I’ve been lost in the details for the past week. My plan for this week is to reread the editorial letter and choose a couple major issues to focus my writing efforts.

But even on the major issues raised in an editorial letter, I’m not likely to agree with the editor on everything. One thing a writer brings to a novel is a unique sense of what makes a story. There are no rights and wrongs in this business, only opinions. My sense of Story (with a capital S) is different from the editor’s sense of Story.

Seldom do I do EXACTLY what a revision letter details. Instead, I read the editor’s thoughts with an eye toward understanding the heart of the issues raised. Then, make revisions based on that. It���s the difference between mechanically following a set of directions and understanding why those directions were given. Don’t blindly follow your editor’s advice: Go to the heart of the issues raised and find your own answers.

Do you struggle with going from micro to macro levels of revision?

October 2, 2015

What Makes a GREAT Bedtime Story?

Swedish psychologist Carl-Johan Forss��n Ehrlin surprised the book publishing world this summer as his book for children and their parents shot to number one on Amazon. The Rabbit Who Wants to Fall Asleep is a self-help book that gives parents a script to follow as they try to get a child to go to sleep. Because of its performance on Amazon, Penguin has picked up the book for a reported seven-figure deal.

Of course, I had to read it. Buzz does sell books.

Rabbit (if I can casually call it by the name of the insomniac main character) reminds me of the Academy Awards ceremony. Screenwriters, directors, actors and actresses, cinematographers and the full complement of support staff for a major move were awarded the highest honor that filmmaking can bestow, Academy Awards. And for every movie about a cause���from elderly rights to gay rights and beyond���the person being honored felt compelled to stand up and explain why their cause was so important and timely. . . thereby negating the art for which they���d just been honored.

Why did they not trust their art to plead their cause in deeper and stronger ways than a week diatribe made during a gala ceremony? It baffles me.

In the same way Ehrlin explains why a good bedtime story works. He has built into the script certain keywords ��� sleep now, yawn, now���which should help put the child in the right frame of mind. Further, he uses some words because they sound calm and slow, thus reinforcing the desired frame of mind. Repetition finds its place as a tool to calm and convince a child to fall asleep.

But why does Ehrlin feel the need to explain it all so blatantly? Perhaps, it���s because parents don���t go behind the scenes for a children���s bedtime story; they don���t understand, and therefore don���t trust, that the writer really knows what s/he is doing when writing this kind of story.

In fall 2016, I���ll join the ranks of authors with a bedtime story, ROWDY: The Pirate Who Could Not Sleep. Let me show you what���s behind the curtain of my writing process.

The Sounds of Words

As a young writer, I once heard Newbery medalist Lois Lowry speak about a story that ended in a quiet moment that she hoped would calm a child and help them sleep. She avoided harsh-sounding words and used soft words. That���s right. The way the words sounded was just as important, if not more so, than the meaning of the words.

Poets John Ciardi and Miller Williams said a similar thing in their classic book, How Does a Poem Mean. They emphasize the ���connotations speaking to connotations,��� an effect they say will create imagery and symbolism. In other words, it matters whether you use the word ���fire��� or ���inferno��� because of how it sounds, its connotations and its definitions. Just as important, though, is how it affects the rhythm pattern of your piece of writing. Fire has only one syllable, while Inferno has three syllables; using one over the other affects the rhythm patterns of the writing.

I have a B.A. in Speech Pathology and an M.A. in Audiology; one of the most useful classes from my college years was phonics, or the study of how sounds are made in the human mouth and how to record those sounds with the International Phonetic Alphabet.

For a bedtime story, you want to avoid harsh sounding consonants, what phonetics calls fricatives or affricatives: f, v, th, t, d, sh, zh, ch, j, s and z. Other sounds to avoid are the plosives: b, p, t, d, k, g. You can���t avoid these two major groups of consonants entirely! But you can minimize them, especially when you want the words to be the softest.

Another distinction phonetics makes is among voiced or unvoiced consonants. Put your hand on your throat and say T ���T ���T ; repeat with D ��� D – D. Do you feel that your vocal cords vibrate for the D, but not for the T? T is unvoiced; D is voiced. Unvoiced consonants are softer, and more suited to bedtime stories.

The softest sounds are the glides: w, l, r and y. These are the real winners for a calming bedtime story.

For vowels, you should understand that some vowels involve lots of tension in the mouth, while some are created with a relaxed mouth. Say a long A; now say AW. Do you feel the difference in the mouth���s tension?

Ehrlin merely takes a clue from phonetics/linguistics and uses relaxed vowels, along with soft consonants.

Why is a rabbit the right animal for Ehrlin to choose for a bedtime story? Rabbit is a relatively calm word: Glide R; short A is relatively relaxed; B is a plosive, but it���s buried in the word���s middle; UH is a relaxed vowel; T is a plosive but because it���s unvoiced, or your vocal cord doesn���t vibrate for it, it���s relatively calm.

My Fall 2016 bedtime story, ROWDY: THE PIRATE WHO COULD NOT SLEEP, is about Captain Whitney Black McKee. She���s a rowdy pirate captain who fights sea monsters and returns to home port, but finds that she can���t sleep. Her crew goes a���thievin���, in search of a lullaby to help her sleep. In the end, the cabin boy brings back her Pappy who sings her a lullaby.

Here���s that last stanza, which you cannot read it harshly because the words, the phrasing and the story that I wrote demand that you say it softly.

Then Pappy sang of slumber sweet,

while stars leaned low and listened.

And as the soft night gathered round.

The pirates��� eyes all glistened.

GREAT bedtime stories include. . .

Child-in-lap relationship. Mem Fox, the beloved Australian writer, talks about the importance of keeping in mind the child-in-the-lap relationship. She means that when you read a story to a child, you are also developing a relationship with that child. She likes to end stories with something that will make the child turn to the adult and give them a hug or say, ���I love you.���

Her beloved book, Kaola Lou, has the refrain, ���Kaola Lou, I do love you.��� And of course, it���s hard to read without also saying to the child in your lap, ���I love you.���

Her beloved book, Kaola Lou, has the refrain, ���Kaola Lou, I do love you.��� And of course, it���s hard to read without also saying to the child in your lap, ���I love you.���

Language development. The great bedtime stories take into account the whole child, not just his or her ability to go to sleep quickly. Instead, they develop a child���s language. Because these are books provided at developmentally appropriate times in a child���s life, it���s an opportunity to entice them with language: the sounds of their native language, the vocabulary, the rhythm patterns and so on. Kindergarten teachers spend time teaching nursery rhymes (Jack be nimble; Jack be quick; Jack jump over the candlestick.) because it develops skills in language.

In a like manner, the classic Goodnight Moon! by Margaret Wise Brown uses rhythm, refrains and much more. Consider the humor of this line: ���Goodnight, nobody.��� It makes for a story that you don���t mind reading for the 1000th time.

Story. As children develop language, an important skill is the ability to understand stories. This involves sequencing of events (beginning, middle, end), understanding cause-effect relationships, character motivations and much more.

Llama, Llama Red Pajama by Anna Dewdney has an appropriately simple story. Baby Llama is tucked into bed, but when Mama leaves the room, he calls that he needs a drink of water. The plot complication is just that Mama is delayed in bringing up the water, so Baby Llama panics. When Mama shows up, she reassures him that she is “always near, / even if she’s / not right here.” It���s a gentle, reassuring story. And while it tells the story, it also gives kids experience in understanding Story.

Llama, Llama Red Pajama by Anna Dewdney has an appropriately simple story. Baby Llama is tucked into bed, but when Mama leaves the room, he calls that he needs a drink of water. The plot complication is just that Mama is delayed in bringing up the water, so Baby Llama panics. When Mama shows up, she reassures him that she is “always near, / even if she’s / not right here.” It���s a gentle, reassuring story. And while it tells the story, it also gives kids experience in understanding Story.

Vocabulary building. Kids love big words���in the right context.

Jane Yolen���s story, How Do Dinosaurs Say Good Night? provides great fun with the names of various dinosaur species. What kid can resist words such as Allosaurus, Pteradon, Apatosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus Rex? But Yolen also includes words appropriate for the bedtime hour. ���Does a dinosaur slam his tail and pout?���

You can���t read this without screwing up your face in a pout, thus teaching the meaning of a vocabulary word in a natural context.

My own bedtime story is titled ROWDY: The Pirate Who Could Not Sleep (to be released Fall, 2016). Will kids know the meaning of ���rowdy���? Doubtful. But within the story���s context, they���ll learn it. Bedtime stories, then, are a comfortable and natural context for teaching new words.

Great children���s book authors create works that don���t need the artificial crutches of bold and italic fonts to tell the adult reader how to present the story. Instead, it���s right there in black and white on the page. It tells a great story that reinforces language and vocabulary development. And when it���s done right, a great bedtime story gives an adult an opportunity to give the kid a hug and a kiss and say, ���I love you.���

Take the Quiz: ARE YOU READY TO WRITE and SELL A CHILDREN’S PICTURE BOOK?

September 28, 2015

3 Tools to Help Part Time Writers Work Smarter, Stay Focused and Track Progress

In a recent survey, 75% of Fiction Notes readers said they write part time.

You’re trying to find time to write.

You’re juggling writing time with family and other commitments.

You’re balancing a job, kids, husband and a passion for writing.

I feel your pain.

While I now work full time, I spent many years as a stay-at-home mom with lots of other commitments. Here are some things I learned.

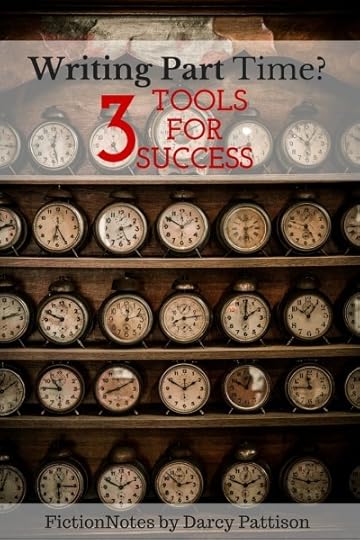

You need tools to write smarter, to stay focused, and to track progress. | Fiction Notes by Darcy Pattison

You need tools to write smarter, to stay focused, and to track progress. | Fiction Notes by Darcy Pattison

Adopt the Right Attitude

I work! Over and over, I said this to people, “I work!”

Writing is work. I happen to love it, but unless and until you approach it as a job – even if it’s only a part-time job – you won’t be taken seriously. You need the support of the local in-house Warm Bodies (your family and significant others). They need to know that when you sit down to write, it’s not just a hobby. IT IS WORK!

That level of respect for your writing is necessary. If it isn’t there, sit down and have some frank conversations. Carve out a time to write and stick with it. Search, juggle, balance–do what’s necessary to create a time for your writing.

Pay attention to your creative process. Now, my work time isn���t YOUR time. When and where to you have the most success? Do you need to get up early, stay up late, or take a long lunch? Do you need a private closet, or can you write in a coffee shop? Think back to a time when your output was at its optimum. When and where were you writing? If your output is down, what changed? Can you go back to old habits. In this search for creative output, habits are your friends.

Your job at this point is to figure out how to do your work, your way.

It may indeed be a job to figure this out. It may take you some time to work through different issues:

Maybe you need to buy a computer for your writing instead of sharing a family computer.

Maybe you need to set the alarm for 4 am and write for two hours before anyone else in the house rises.

Maybe you need that frank conversation with your children, your husband, your mother-in-law, or your _______(fill in the blank)

This is your first task: figure out how to do your work, your way.

Use the Right Tools

Next, I’m going to make suggestions for some tools that can help.

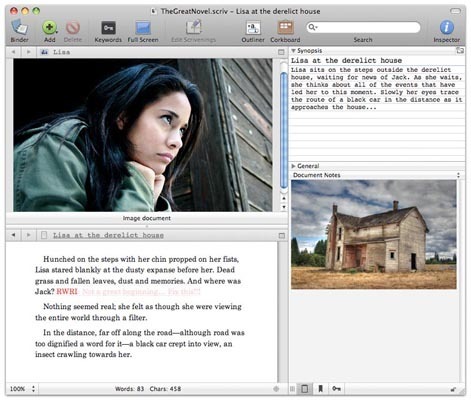

Scrivener. First, you need to outline. If you write by-the-seat-of-your-pants, it’ll be harder to make it writing part time. You’ll save time and energy by learning how to outline and how to follow an outline. Your creativity will increase and you’ll be happier with your first drafts – which will save time when you revise.

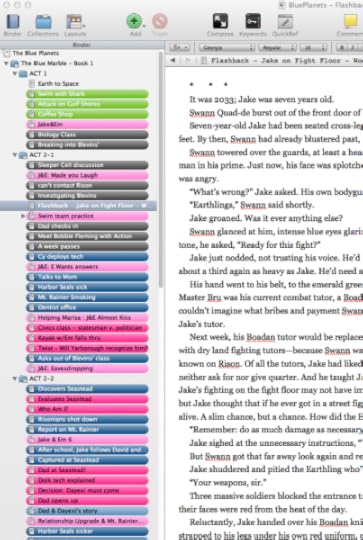

This screenshot of Scrivener shows how I use colors to help organize my outline.

This screenshot of Scrivener shows how I use colors to help organize my outline.

In the corkboard view of Scrivener, index cards show the flow of my story.

In the corkboard view of Scrivener, index cards show the flow of my story.

To outline, you probably need Scrivener, the software that is created especially for writers. The screenshots above show my work-in-progress. Besides these views, you can also get rid of all the outline stuff and have an empty screen on which to write, only coming back to the outline when needed. Lots of flexibility with this program!

I hesitate to recommend Scrivener because, well, it’s complicated. In the short run, you’re going to spend a couple months writing slower and learning the program. In the long run, though, part-time writers need to write smarter, and that’s what Scrivener facilitates. It’s not that you’ll write better just by using this software or that. But Scrivener encourages and makes it easy to create and use outlines. You need that in order to stay organized and write smarter. Especially as a part-time writer, you need this program.

WRITE SMARTER: Scrivener and Scrivener Resources

Here are some resources for getting started in Scrivener. You’ll need to invest in your writing career and take a tutorial, buy a book or something to get up to speed as quickly as possible in Scrivener.

Note: Some of these links are affiliate links. When you click, at no extra cost to you, I’ll receive a small commission. I appreciate your support.

Buy Scrivener. You definitely want to start with a trial version!

Buy Scrivener 2 for Mac OS X (Education Licence)

Buy Scrivener for Windows (Education Licence)

During your trial period, you’ll want to TRY the software. Use the interactive tutorial included. Scrivener also maintains an extensive YouTube selection of specific tutorials.

That may be enough for most of you, but around the Scrivener program, there has grown up a cottage industry of folks who provide extensive tutorials. You may want to find one that’s tailored to the type of writing you do. Anything you can do to get up to speed on the program will help down the line.

Scrivener courses. (Not an exhaustive list, but a place to start.)

Because there are so many options, look for reviews and look for features that specifically relate to the genre in which you write.

Scrivener Unleashed

Gwen Hernandez Scrivener Courses (I started here.)

Learn Scrivener Fast

Simply Scrivener

Scrivener books.

Scrivener for Dummies by Gwen Hernandez

Scrivener Essentials – Mac by Karen Prince

Scrivener Essentials – Windows by Karen Prince

General Books on Organizing Your Novel: Outlining, Thinking it Through, and Smart Revising

Start Your Novel: Six Winning Steps Toward a Compelling Opening Line, Scene, and Chapter by Darcy Pattison

Million Dollar Outlines by David Farland. An amazing book!

Outlining Your Novel: Map Your Way to Success by K.M. Weiland

Outlining Your Novel Workbook: Step-by-Step Exercises for Planning Your Best Book by K.M. Weiland

Novel Metamorphosis: Uncommon Ways to Revise by Darcy Pattison

STAY FOCUSED: Get Offline

I know. As soon as you fire up your computer, you’re tempted: Facebook, email, Twitter, Pinterest, browsing, cruising the internet. . .

No. Stop.

Your writing time MUST be your writing time. Nothing else.

For some people, they find that they need help to turn off the internet.

Freedom. Freedom is one of the many programs that isolates your computer from the internet for a specified time interval. It works for me. If you don’t like this one, or it’s not for your kind of computer, search for something similar. And use it. As with other software, do a trial version before buying.

TRACK PROGRESS: Numbers

Finally, you – the wordsmith – need numbers. You need some accountability and numbers give you that. You should be tracking your writing somehow so that over time you can understand your writing self better.

Scrivener tracks words per session. Scrivener easily tracks number of words per writing session. When you set up project tracking, you can set a goal of finishing on a certain date. Scrivener then says, “OK, if you want to finish by XXX date, then you must write ZZZ number of words per day.” It will tell you if you meet that daily goal and show you a progress bar for your project.

Toggl. If however, you want to track time, find a simple app like Toggl that tracks the amount of time you spend on a project; you can also track WHERE you were working. It’s simple and syncs between desktop and mobile. Reports are easy to set up for each project.

Tracking in and of itself will do little to help you. Instead, set up a schedule – weekly, monthly, quarterly, yearly – to look over your numbers and evaluate. You may discover that when you write at a coffee shop, you can only concentrate for 15 minutes at a time; however, during that 15 minutes, you produce twice as many words as any other time frame. Whatever you discover, use the info to fine-tune your writing process.

Your Main Job

Remember, your main job is to figure out how to work on your work.

Then, your job is to DO your work.

These three suggested tools are just that, a suggestion. I know that outlining has the potential to increase your efficiency, while creating stronger stories. But if you absolutely hate it – do your work, your way. Don’t just discount this advice out of hand, though. Try it. Give it an honest shot. But if it doesn’t help, it doesn’t.

The same for the other suggestions. I like Freedom and Toggl; but find tools that work for you.

Basically, you need tools that help you write smarter (get more done in a shorter amount of time), help you stay focused (turn off distractions), and help you track your progress in ways that will make a real difference.

Writing part time is hard. But it’s doable. If you set yourself up for success–by using the right tools–you can do this.

Be sure to send me your good news!

September 21, 2015

Science Fiction and Fantasy Worldbuilding: Timeline Adds Crucial Details

One of the first tasks in revising my current WIP has been to nail down a firm time line for my story. When does all this stuff happen? I had it vaguely placed in the 21st century, but I didn’t want to nail it down specifically.

It’s the EveryMan problem. Some writers try to create an EveryMan, a character who can stand in for everyone and anyone. In doing so, though, they create a generic character who fails to engage the reader and becomes NoMan. To write something universal, you must do something that intuitively feels like a paradox: you must write one specific character. Only by doing this do you have a chance of letting the character live in the reader’s imagination in such a way that the character stands in for EveryMan (or EveryWoman).

I was making the same mistake with the timeline of my sff story. By refusing to set it in a specific time, I was going too generic.

Creating a TimeLine for Your SFF Story

However, I also see the wisdom of waiting till I finished the first draft to nail down the time line. It will mean, perhaps, that I have more revisions to do; however, I feel that it’s a strength to have this first draft done to see how the timeline extends into so many places.

How Old are Your Characters? One of the first things I’ve done is write out everyone’s birthday. The main villain was born in 1980, and his son–the minor villain–was born in 2013. That means the father was 33 years old when his son was born. It was his first child, so why so old? It make sense within this story because the father is a scientist who buries himself in his work and generally neglects his family. He didn’t marry till after he’d done a post-doc in volcanology, and after his son is born, he travels extensively for his work. This affects the father-son relationship! The timeline forced me to think about these aspects of character.

I also knew that the main character is 14. Okay. How old are his parents? A minimum of 30, but they could be as old as 50 or so. What made sense for their relationship?

World Events. Slotting characters into a personal time line also means they exist in the world at a particular time. If someone was born in 2001, for example, was it before or after the World Trade Center bombing? The world tilted on that day and it’s important to place your character in the context of world events.

But even in a wider context, I needed to place this science fiction story in the context of astronomer’s exploration of the universe. The Kepler Space Observatory was launched in 2009 to search for planets similar enough to Earth that humans could live on them. I had to consider the timeline of their findings, and make sure my characters and the plot were aligned with that.

Imagined Events. Only once these elements were in place did I try to place my imagined story elements. Science fiction is only believable when it fits into the established world. I had to make sure that the events were believable in the context of the real history of our world. That doesn’t mean that I can’t do crazy and wild things–science fiction can and does stretch the imagination. It does mean that the events need to be based on some bits of truth that will lend it credibility.

World building for fantasy or science fiction is crucial. Rules are set up that control the story world, and once set up, the story is stronger if you stick to those rules. The timeline–in this revision of the first draft–was a crucial thing for me to nail down, and it’s adding surprising depth to the story.

September 7, 2015

In Praise of the Humble Sentence

Voice is the quality of writing that lets a reader see the author behind the work. It’s what makes a piece of writing unique so that you and only you could have written this piece. I don’t look at it as a mystical thing; instead, I look to the tools that writers have to work with: words, sentences, and longer passages. Here are three ways you can use sentences to help you find the best voice for your story.

Write ten openings. It’s said that the first word and first sentence of a story setup everything that follows. If THIS is the first sentence, what sentence MUST follow? What does the story and your storytelling voice DEMAND for the second sentence?

For example, let’s take a couple sentences and see what they demand next.

It was a dark and stormy night.

I would expect something about the night, the storm, more on the setting, the character’s reaction to the storm, and so on. That first sentence demands that the second comment on the night or the dark or the storm or the character in the situation. It would be a non-sequitur to follow that sentence with something like this: The bunny hopped through the sunlight.

The first sentence narrows the possible choices to a dozen or so topics. And the second sentence will narrow the choices even further. By the third, the story is locked in for at least the space of a couple paragraphs; of course, those paragraphs will lock in the next several paragraphs and so on.

This is why it’s so valuable to write multiple openings to a story. Each opening will set up topics, characters, settings, tone and voice that will send the story in a different direction. That’s what you want at first: options.

Mimic a text. On the other hand, I’ve also found it helpful to choose a text that I like and mimic the sentence pattern.

Here’s the opening sentence from The Green Glass Sea, by Ellen Klages, a story about a girl whose father is working on the atomic bomb during World War II.

Dewey Kerrigan sits on the concrete front steps of Mrs. Kovack’s house in St. Louis, waiting for her father.

Sentence Pattern: Proper-Noun verb prepositional-phrase prepositional-phrase prepositional-phrase, participial prepositional-phrase.

My sentence: Darcy Pattison runs through the historic neighborhood on top of the hill across from Little Rock, hoping for a miracle.

You’ll find out a lot about your own writing style and your unconscious habits of writing. One friend always writes in complex sentence with lots of phrases and clauses; it’s appropriate for her complex non-fiction styles. But when she’s tried to switch to writing simpler picture books, it doesn’t work.

Imitating or mimicking another person’s sentence structure is an interesting exercise for learning more about your writing and for exploring different voices.

Vary sentence patterns. Here’s an exercise I love. Take one page of your writing. Count the number of words in each sentence and write that number at the end of each sentence. Now, rewrite following this rule: each sentence must be at least plus or minus 4 from the previous sentence.

For example, if sentence #1 is 10 words, sentence #2 must be 10-4=6 or less OR 10+4=14 or more.

Let’s say, you went for a longer sentence, so sentence #2 is 16 words long. Sentence #3 must be 16-4=12 or less OR 16+4=20 or more.

This forces you to vary the sentence lengths: 10, 16, 3, 8, 20, 2.

Those varying sentence lengths give your writing rhythm and add to the meaning of the words.

It’s a funny mechanical exercise that yields amazing results in your writing. Once, I tried to figure out why this one small thing should matter so much. I looked at some essays by students in eighth grade. Amazingly, their sentence lengths were uniform, almost all about 12 words long with the shortest about 8 and the longest about 15. Not surprisingly, the voices were bland.

If you read The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo, you’ll find some of the most variety in a text that I’ve seen. She writes one word sentence fragments, followed by 30-word sentences. Why is it a great story? Because she’s a great storyteller? Yes. But also because she has command of her words and language, especially the sentence variety.

As writers, we only have words, sentences and longer passages. Those are our tools. Milk sentences for all they can add to your story’s voice.

August 30, 2015

The Editorial Dance: Finding the Right Editor

I talked with an editor earlier this week about my new novel, The Blue Marbles, a sff YA and found that editorial input comes in two forms–and these are so important to finding the right editor for your story.

Positioning in the Market Place

The first thing we talked about was our visions for the story, to see if we meshed. This is very much a marketing discussion. Where does the story fit into the marketplace? Who would read this book? Is this a middle grade or a YA?

Vastly important, you must know your audience because it determines so much of the next question about the quality of the story. If my story is a YA, it means that I need to follow certain conventions of the genre. The protagonist should be of a certain age; he’s got a certain outlook about dating and girls; he’s reacting to family in certain ways. It brings up questions such as should he be able to drive or not? If the story is middle grade, the tone of the story would be very different. The answers to the questions would be vastly different.

Even saying that it’s a YA, isn’t quite enough. Is it a young-YA or is it closer to the New Adult category? In other words, will the tone of the romance involve just a brief kiss or something much more physical.

What happens when you disagree with the editor’s opinion of where to best sell this story? I’ve seen writers struggle with this because they want to write a YA. They read YAs; they talk YAs; they live YAs. But when they write, what comes out is a middle grade. Sigh. It’s frustrating. What you love isn’t necessarily what you can write. (At least not yet.)

YOU want to push the story to a YA; the editor wants to push it to middle grade BECAUSE she thinks s/he can sell the story there.

In some ways, this is a career question and not just an editing-this-novel question. Where do you have the best chance of creating a career for yourself? HINT: It might be different than what you thought.

Writers are notorious for not SEEING clearly what we write. Sometimes, you have an inkling that, well, this might be middle grade instead of YA. But you don’t WANT it to be MG; you love YA. Sorry.

An editor’s strength is that s/he has a pulse on two things: great story writing and marketing great stories. For an editor, those two things must match up. And you, as the writer, must either trust that editor or find a different one. You must also decide if you want a career based on the editor’s positioning of the book in the marketplace. If it’s positioned as a middle grade, can you–do you want to–follow up with a second middle grade? Because careers are built on building a readership who consistently comes to you for a certain type of story.

When a manuscript sells, your first thought is celebration! Yahoo! Your second thought is, “What next?” To build a readership, what story is the logical follow-up. When someone reads THIS story, which of your possible stories would they naturally pick up next and love just as much or more?

This question of the editorial marketing vision for your story is crucial. You must share your editor’s vision for the story. Otherwise–it may not be the best fit for you, your story, and ultimately, your career.

Tell the Best Story Possible

The second thing a great editor can do it help you create the best story possible, given the shared vision.

For me, the discussion had some themes I’m familiar with:

Setting. While my natural world settings were strong, when the story veered into a school–where the YA would be very apparent–I need more work. Setting is crucial to making sure the reader is grounded in your story.

Raise the stakes. The editor suggested a change that would raise the stakes of my story. The reader should always be invested in finding out what happens next, and if you can put more at risk, the stakes pull them through the story.

Emotional resonance. On a similar note, the emotional story should resonate with the reader and impact them in some way.

Everything we discussed seemed reasonable and necessary because we were heading toward a mutually agreed upon goal. Without the shared vision, the specifics of a revision are agonizing; with a shared vision, revision is like dancing with a friend, where you mirror each other’s moves in perfect harmony.

August 24, 2015

Don’t Write a Damsel-in-Distress OR a Modern Super-Woman: Be Original

I have a problem in my WIP novel, which is just in the outline stage. There���s a specific illness going around and to SHOW, DON’T TELL that the illness is really bad, an important character must become sick.

But then, I have this sick character, Em. And she���s, well, sick.

She���s become a Damsel-in-Distress, who has no active part in the story. She���s a weak love interest, whose only role is to be sick and provide motivation for the main character.

It���s a good motivator. Jake, my main character, really cares for Em, and he���ll do almost anything to find a cure. From that side of things, it���s working. But Em is still just a sick���and-convenient���character.

I���ve given Em some other character problems. She���s adopted and is looking for information on her birth parents. They���ll come into the story and the intersection of these characters will give Em some rosy cheeks of health. Her subplot will be one of discovering who she really is.

But the excitement doesn���t last long enough for her. She has a crisis in her health, which is necessary to get Jake moving. Again, Em becomes a sick, convenient, unappealing and placid character. How do I provide some sort of action around a sickly character?

There are precedents for sick or sickly characters.

Angelic character and how the illness and/or death affect the main characters. In Little Women, Beth dies from scarlet fever. While her health wastes away, she is active, though, knitting and sewing clothes for neighborhood children. Her death is a major impact on Jo���s life, the main character. By giving her selfless acts to perform, it elevates Beth. She���s angelic in everything, never complaining and dying without a lot of fuss. By elevating Beth���s moral character, we understand why her life was important.

Imaginary life. In Paul Fleischman���s Mind���s Eye, a paralyzed girl leaves the real world behind in an imaginary trip across 1910 Italy. Here, Courtney comes alive in her imagination. She and her nursing home roommate, 88 year old Elva, use a 1910 Baedeker guide to catch trains, to travel and to live. It reminds me of a Star Trek episode about Captain Pike, the original captain of the Enterprise, who is injured and in a wheelchair. There���s a forbidden planet, and we find out that it���s forbidden because the inhabitants live a virtual life. On that planet, however, Pike can live a happy and full virtual life, walking and climbing wherever he wants. Like Courtney, Captain Pike chooses the illusion of life over the reality of his paralysis.

Give the sick character an amazing POV voice. John Green���s character in The Fault in Our Stars is suffering from cancer, and indeed, the whole story is about living with a death sentence in your lungs. The narration is from her POV and it���s a distinctive voice.

Entwine the emotions. In My Sister���s Keeper, Jodi Picoult poses an interesting dilemma. A younger sister is conceived for the specific purpose of donating an organ to her sickly older sister. The sisters, though, are both active to an extent and the real success here is how the emotional lives are entwined, just as their fates are interwoven.

Writing Sickly Characters

Here are some take-aways for my own writing.

Sick, but not incoherent. A character can be physically challenged or sick, but there must be lucid moments where the character���s life and personality emerge. Em can be very sick, but the illness must ebb and flow. And develop her personality, hopes, dreams, fears, anxieties, dreams, etc. as possible.

No griping. Okay. Em feels lousy. But no one wants to read about a character who complains her way through the actual horrors of the human form when it���s sick. No explicity descriptions of throwing up, other bodily fluids, etc., at least in MY stories. Instead, the sickly person rises above those things and we see her character, not her illness.

Emotional impact. Sick or not, people are invested deeply in Em���s life. They want to be with her and they care about her thoughts, emotions, reactions, etc. Perhaps, she must be even more entwined than usual in the main character���s life.

Action when possible. When she���s feeling good, I’ll give Em as much action as possible. I’ll look for both major and minor actions. Maybe stealing a cell phone and making a forbidden phone call is enough of a physical challenge, while also moving the plot along in some way. Look for ways to add action, arguments, and conflict. Just because she���s sick, she doesn���t get away with an easy life emotionally. Otherwise, where���s the story? Story requires conflict and even sick people in your story must endure the conflict���or there���s no story.

Rescue. Well, it���s OK. Em might need to be rescued. I know, gender roles these days decree that she not be a Damsel-in-Distress; instead, she must be the conquering princess who fights the dragon herself and saves the poor, incompetent prince. But that���s a modern trope that is just as bad as the damsel-in-distress trope. The challenge will be to create a unique, living character without falling prey to either clich��.

In short, sick or not, Em must be a real character. She���s no damsel-in-distress; neither is she the modern woman who rescues the weak men in her life. Instead, she pursues her goals with the same fervor (and whatever physical strength she can muster) as the main character, Jake. It���s a plan.

August 17, 2015

Where Am I? Setting the Scene

I’ve been reading lots of manuscripts lately and a common problem keeps arising. As a reader, I keep wondering, “Where am I?”

The plot and characters are often interesting, but I’m lost. I need a map to figure out where I am. In other words, setting is crucial to keeping your readers grounded in your story.

When?

Often, the problem is that I don’t know WHEN the story is taking place. This could be anything from what century to what season of the year. The simple detail of a Christmas tree might be enough to reorient me to the setting. Or I might need details of clothing worn in 1492 to understand the setting. Either way, the relevant details must be woven into the story. However, you can often just add a simple phrase to indicate time: early that morning, an hour later, or meanwhile.

Where?

The WHERE question can be much more complicated because it should be woven into the story seamlessly. One writer recently said that she was afraid to bog down her story with lots of description. That fear kept her from adding details that would keep the reader grounded. Novels aren’t screenplays or movie scripts; for those, you expect the production to fill in the blanks. For novels, though, you must play the movie in the reader’s head for them.

Beats in dialogue. This is especially important in dialogue or conversations between characters. Another writer had nice dialogue, but it was all in isolation–talking heads. You must remember that the characters are people who fidget, move around, blunder around or just nod their heads. Of course, sometimes you DO want a section that focuses on words. But even there, the right detail at the right time can emphasize a point, add comic relief, or make the story more believable.

Setting comes alive when you have the right details, usually sensory details. If you were a character in the story, in this particular scene, what would you see, hear, smell, touch, or taste? Description comes down to the careful use of our senses to put the reader into the scene.

Often, I’ll create a sensory details worksheet. Down a side of a page, I’ll write the senses: See, Hear, Smell, Touch, Taste. Then, for each sense, I try to find three details unique to the setting. I’m also trying to do it in language that would be used by the POV character.

Be specific as you do this.

Not: dog

Instead: Pit Bull

Notice that I didn’t say, “Big Dog.” The use of modifiers–adjectives and adverbs–weakens a story. Instead, I search for a more specific word, such as the name of a dog breed. Only after the verb or noun is as specific as possible do I allow myself to add modifiers.

Not: dog

Instead: Pit bull

Even Better: pit bull with a white-tipped tail

Be reasonable. Sometimes, “dog” is enough, depending on the story, where you want the reader to pay attention, and the intended audience. For a toddler’s story, Dog would be reasonable. Mostly, though, writers need to be more specific and avoid those adjectives that work as a crutch, but really add nothing to the description: good, nice, big, small, etc.

A special note on Touch/Feel: Often writers want to translate this into emotions. Instead, I mean this as a physical sensation of touch, usually temperature or texture.

Not: I loved my lunch.

Instead: The chili burned my tongue.

Once I have a list of sensory details, I like to start a scene with a unique detail. I search the imagined setting for something that will make a reader stop and pay attention. Here are some descriptions from the first pages of my Aliens, Inc. Series. The series is for 1st-4th grade readers, and each story begins in art class. Use the links to download sample first chapters to read more.

“Mrs. Crux, the art teacher had put a blue bowl of fruit on each table and said, ‘Paint this.'” from Kell, the Alien, Book 1, The Aliens Inc. Series

“I swiped a streak of red across my paper.” from Kell and the Horse Apple Parade, Book 2, The Aliens Inc. Series

“I bent over the giant state of Texas.” from Kell and the Giants(Listen to the audiobook sample), Book 3, The Aliens Inc. Series

“My hand dripped with blue paint.” from Kell and the Detectives (audiobook sample), Book 3, The Aliens Inc. Series

Balancing Description and Narrative

It’s impossible to tell you how to balance the narrative descriptions, dialogue and action. As an author, you need to learn which area you are strongest in and which is your weakest area. If you consistently get the response from readers, “I’m lost,” then you need to provide more description. Don’t fear the descriptions. They won’t slow down the reader unless you really go overboard. But they can sure LOSE you a reader, if you get them lost. They won’t trust you to tell the story and will stop reading.

In other words, listen to your early readers. If they are confused about what is happening, your descriptions are weak. If they are drowning in detail, the story will feel slow-paced. Work to find the right balance for your story and your readers. Just be sure they never get lost.

August 12, 2015

Indie Kids Books Listserv

As you know, I’m a hybrid author, with some traditionally published books and some published. I’ve written about the process here on Fiction Notes, and on Jane Friedman’s blog here and here.

Indie publishing, especially of children’s books, is hard. I listen to everything that those who write for adults talk about and try to adjust strategies to the world of children’s literature. And mostly, things don’t translate.

So, I’ve decided to try to bring together those who write for children and are involved with independent publishing or self-publishing.

Indie Kids Books Listserv

The purpose of the group will be to discuss independent or self-publishing as it relates specifically to children’s books: nonfiction or fiction, for readers from birth to 18. We’ll discuss writing, illustrating, publishing and marketing your books. Join the listserv discussion group by sending an email to

IndieKidsBooks-subscribe@yahoogroups.com

The group is just forming–get in on the ground floor!

Pass this along to anyone interested, whether they have books published or are just thinking about it.