Darcy Pattison's Blog, page 10

January 11, 2016

Start! Again. And Again. And Again. . .

Coming February 9!

PreOrder Now!

In their wise book about the nature of making art, Art and Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, David Bayles and Ted Orland say that people don’t STOP writing. Instead, they fail to begin again.

Beating the Holiday Stops by Starting Again

Today, I’m trying to beat the holiday STOPS by starting again. And I feel the resistance. I love my current WIP. I’m excited by the possibilities. I see the problems and have possible solutions to try. And yet —

Putting words on the page/screen is hard. I don’t know where to start. The story is a bit convoluted right now and I’m not sure I can solve the problems, even though I have strategies to try. I’m unsettled, unfocused, uncommitted. Pulled in too many directions.

And yet, a writer is a person who writes.

It’s comforting to go back to ART AND FEAR and reread that the core problem is to begin again. I must start. And it almost doesn’t matter where.

When I taught Freshman Composition, I often had students who balked at writing. After all, I had only the average students. The A/B students tested out of taking Freshman Comp. The D/F students didn’t come to college. That meant I had a class full of B/C/D average students. Often, they planned their entire schedule around my class. They had nothing before my class so they could write something at the last minute. They had nothing after my class, so they could hide in their room and weep. They did not WANT to write.

My advice was to write. Move the pen across the page. Do not stop moving the pen across the page until I tell you to stop. If you don’t know WHAT to write, copy this sentence over and over until you want to write something else: “I don’t know what to write, but I have to write something, so I’m writing this.”

Never did a student write that more than twice, because it’s so boring, so obvious. Instead, they’d launch into a tirade about how they really, honestly, completely didn’t want to write. But guess what? They were writing. And soon, they realized griping about writing was boring and started to let their more intelligent thoughts find their way to the page.

It’s the same advice I give myself. Write.

Anything.

It doesn’t matter.

Write a blog post.

Write a description.

Write a scrap of dialogue.

Write. Let the first word lead to a second word, and that leads to a third and fourth. And so on.

Write.

I’m going to write now. I hope you Start Again, too.

The post Start! Again. And Again. And Again. . . appeared first on Fiction Notes.

January 4, 2016

Grand Entrance: Pay Attention to This Character

In honor of Jacob Grimm's birthday,

this retelling of Hansel and Gretel is on sale: 10%

LEARN MORE.

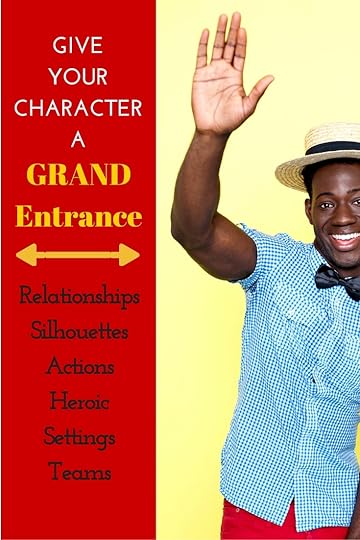

How do you introduce your character to your reader? Do you give the character a grand entrance or sneak them in while the reader is focused on something else? A grand entrance signals to the reader that this is a character they should pay attention to. Let’s talk about some ways to make this happen.

First, a couple reminders. Great storytelling is built on the foundation of sensory details. When you provide visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory (taste) or actions, the reader becomes immersed in the story as if they were actually present. You can use sensory details to create a zoom, a pan or a scan. A zoom focuses on tiny details; for example, a face fills the entire imagery, with minute details about each feature. The zoom can travel: you may start by describing in detail the character’s shoes and then travel upward to the face. Or start with any significant detail and then pull back to see the whole. For a surgeon, perhaps describe her clever hands and then travel to her scrubs and finally to her face.

At the other extreme, a panorama pulls back to a bird’s eye view of an entire village. A scan is a method of handling a crowd scene by using specific details to represent a general sense of the mass. For example, a scan might do a mini-zoom in on an old man stumbling along with a cane, then quickly move to an infant taking tottering steps, and then contrast those with a strong young man pushing everyone aside. The series of mini-zooms gives a flavor of the crowd, making it more specific and thus more interesting.

Also, remember that story openings work best when they are focused on a scene. Long-winded descriptions might have worked a hundred years ago, but are less successful for today’s impatient audience. Instead, stories succeed when they start with a character who wants something and faces obstacles to their desires. In short, a scene.

With those givens, a grand entrance–the introduction of a main character to the reader–should take place within an active scene. And you’ll have a choice of a zoom, a pan or a scan. Within those parameters, there are other options.

In Context of a relationship.

The first time we see Katniss in Hunger Games is telling. There’s an opening sequence that sets up what the Hunger Games are, and then there’s a scene cut to Prim screaming. Katniss hugs her, calms her, sings to her. The images are close up, zoomed into Katniss’s and Prim’s faces, as they face the knowledge that the Reaping happens that day.

If you can’t see this video, click here.

Silhouettes.

Sometimes the sensory details focus on silhouettes and shadows, often with a blinding light behind the character. Think Psycho (1960) and the silhouette on shower curtain (often parodied). This works well when the character likes to hide in the shadows until it is time to reveal themselves. This works well then timed for effect with a dramatic piece of dialogue.

Actions.

Often, beginning with the character in action makes for a grand entrance. Think of the Bridal March: the audience rises and turns to watch the bride make the long walk down the aisle. Everyone’s full focus is on The Walk. Or think of the Red Carpet arrival of celebrities at a premier or awards ceremony. It doesn’t have to be a Walk, though. For a basketball player, but him on the court and let him score with his signature hook shot. Or show a doctor doing chest compressions as a snow sled skims down a ski slope.

Heroic qualities.

Donald Maass, in his Breakout Novel Workbook, asks, “When does the reader first notice the heroic qualities of your character?” As a writer it’s helpful to think about what makes a character heroic in your own eyes. Then ask how you can present that quality the first time the character appears in your story.

In context of a setting.

Sometimes, the setting is crucial to the story. It may be a space station or a hospital surgery or a swimming hole, but something about the setting is crucial. Here, you could give a short panorama of the scene, and then slowly zoom in to the character and what s/he is doing within your setting. Another option is to scan across a scene (mini-zooms of several people), then abruptly come back for a double take of your character.

Group – Team is in Place.

Perhaps, the group of characters is just as important as the main characters. In this case, the Team needs a grand entrance, just as much as the main character needs one. Here, you might zoom in on the main character standing alone, and then slowly pull back as one-by-one others join him/her. The focus begins with one character but ends with the group as a cohesive character of its own.

Alternatives to the Grand Entrance

Anti-Grand Entrance. For my WIP, I was thinking about all of these options for a major character and eventually rejected all of them. Instead, I slipped my character in on the sly. Jake, the main character, is waiting in the Emergency Room waiting area for his turn to be seen by the doctor. He’s distracted by a huge salt water tank and talks to an older woman who is cleaning the tank. Later, when he goes back to see the doctor, he discovers that the woman cleaning the aquarium is the doctor. This works in my story because one of the themes is hiding in plain sight. Jake dismisses a woman as someone who just cleans aquariums–and reveals things that he wouldn’t normally tell the doctor. It’s a bit of misdirection because Jake makes wrong assumptions.

Second Grand Entrance. Another idea to consider for grand entrances is that sometimes, a character needs a second grand entrance, after some life-altering change. In Dicken’s “Christmas Carol,” Scrooge awakens the next morning as a changed man. He walks to the window and throws it open. Ah, what nice imagery. He’s looking out on a new world! He calls to a boy to fetch the large goose and have it delivered to the Cratchit family. This second grand entrance stands in contrast to the first grand entrance of Scrooge and tells the reader that a huge character change has been accomplished.

Whatever approach you choose, think hard about the reader’s first impressions of each major character. It is true that first impressions matter.

The post Grand Entrance: Pay Attention to This Character appeared first on Fiction Notes.

December 21, 2015

Slight: What Does an Editor Mean?

Thanks, L.A. for the question for today. She received a rejection that called her picture book manuscript, “slight.” What does an editor mean by that term? And what can you do about it? (BTW, I love questions! Send me your questions and I’ll try to do a post on it.)

When by nonfiction book, Praire Storms was accepted by Arbordale, the editor said they had several prairie books to consider that year and choose mine because it had many layers. It’s the story of how prairie animals survive during a storm. But that’s not all it is.

When by nonfiction book, Praire Storms was accepted by Arbordale, the editor said they had several prairie books to consider that year and choose mine because it had many layers. It’s the story of how prairie animals survive during a storm. But that’s not all it is.

The layers include prairie animals, how they fit into that landscape, storms, and the months of the year/seasons. It wasn’t enough just to write a story with animals and their habitat. The addition of storms made sense, because on the prairies, the skies are such a big part of what you see. But I also knew that the Next-Gen Science Standards for K-3 emphasized the relationship between animals/habitats, and also how weather shapes the Earth. The book could be used to emphasize a variety of standards across K-3, or even into 4th or 5th for classrooms that used picture books.

Even that wasn’t enough. I also decided to include 12 animals and to feature one per month. Elementary students are learning about the months of the year and the seasons, so that added yet another layer that made it appealing in the classroom. Finally, I think the writing was a factor. I wrote the story first in poetry, but then reworked it as prose, because Arbordale usually translates their books into Spanish and prose is easier to translate. However the poetic feel came through in the revision. The poetry draft gave me language and rhythm patterns that made the book a stronger read aloud.

Adding Layers to Your Story

Study curriculum standards. To add layers to your own story, consider the various curriculum standards to see if there’s something you can layer over the story. It’s not the most important factor in selling a book, especially a trade book; however, any consideration of market is always appreciated. Make sure the layer is integral to the story and not forced, or it won’t work. When you write your cover letter, be sure to mention that you’ve added these layers; or consider adding a note at the end with info on how the mss can be used for certain standards.

Next-Gen Science Standards – easily searchable database.

Common Core Curriculum

Social Studies Teachers

Environmental Education + Common Core

STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math)

National Core Arts Standards

American Association of School Librarians Standards

Other standards that may apply to your story.

Language. I used a poetry draft to enhance my writing of Prairie Storms. It’s just one way to get to the idea that you need a story that’s a great read aloud. The language of the story should pull the reader along and be pleasant to read over and over. Read more on creating a satisfying read-aloud picture book.

What’s the Takeaway? Finally, consider the theme of the story. This is similar to the morals of the Aesop Fables. However, you shouldn’t bash the reader over the head with the story. Instead, the takeaway is the overall point of the story, whether stated or not. Often, it’s NOT stated explicitly, but is something the reader/listener will understand as a result of the story. It’s the answer to the question, “So what?”

In Prairie Storms, this is the weakest element with only a hint of a takeaway in the last line: “The bison stand, prairie-strong and defiant.” I meant that in a more general way for all the animals featured, that they were strong, and the prairie was a stronghold for wildlife in America. Defiant, for me, meant that even in the face of environmental problem, they would survive. After all, the bison have escaped extinction. It’s a stretch, yes, and I could’ve done more to make the takeaway explicit. Sometimes, I err on the side of understatement!

For your story, add layers: historical, literary, technical, or emotional layers. And you’ll never get that dreaded rejection note that says, “Too slight.”

December 14, 2015

Nominate Fiction Notes for Top Writing Blog

Dear friends –

This is a combination of two things: a list of popular posts in 2015 and a request for help. For the past two years you’ve been kind enough to nominate Fiction Notes as a Top 10 Blog for Writers. I’m asking if you’d be kind enough to do it for 2016.

WritetoDone.com, who sponsors the contest has new rules for 2015 – please read carefully.

To Nominate your favorite writing blog, you need to do 3 things in the comments section of this post:

Nominate only one blog post from your favorite writing blog. If you nominate more than one blog post, even in different comments, only your first vote will be counted.

Specify the correct web address of the blog post you���ve nominated.

Give reasons why you believe the blog post you���ve nominated should win this year���s award.

If your comment does not fulfill these criteria, your nomination will be invalid.

Conditions:

Only posts from writing blogs will be considered.

The blog post you nominate should have been first published in 2015.

You nominate a specific blog post, and that blog becomes a candidate for the Top 10 Blogs for Writers 2015/2016.

Nominations must be received by 24th December, 2015.

Click here to Nominate Fiction Notes for a Top Blog for Writers

So, it’s a bit different because you must nominate with a specific blog post, not just the overall blog itself! And the blog posts must have been written in 2015. I hope this list of top 10 blog posts from 2015 will help – the URL is provided for your convenience, too.

TOP 10 Blog Posts for 2015 include topics of marketing, characters, and revision

TOP 10 Blog Posts for 2015 include topics of marketing, characters, and revisionTop 10 Fiction Notes Posts for 2015

Top 20 Picture Book Agents – 234 Sales in Last 12 Months – http://darcypattison.com/marketing/top-20-picture-book-agents-2015/

Top 20 YA Agents – 72 Deals in Last 12 Months – http://www.darcypattison.com/marketing/top-10-ya-agents-72-deals/

Top 20 Middle Grade Agents – 129 Sales in Last 12 Months – http://www.darcypattison.com/marketing/top-20-middle-grade-agents-2015/

Find Your Novel’s Opening: Quickly, Efficiently – and with MORE Creativity – http://www.darcypattison.com/first-drafts/find-novel-opening/

Don���t Write a Damsel-in-Distress OR a Modern Super-Woman: Be Original – http://www.darcypattison.com/characters/dont-write/

10% of My Traffic Comes From Pinterest: Expand Your Author Platform – http://www.darcypattison.com/marketing/pinterest-for-authors/

Openings: 5 Ways Openings Go Wrong – http://www.darcypattison.com/revision/openings-5-ways-they-go-wrong/

What’s in Your Writer’s Bag of Tricks? Putting the Writing Process in Context – http://www.darcypattison.com/revision/writing-process/

Is My Story Good or Bad? Wrong Question -http://www.darcypattison.com/revision/is-my-story-good-or-bad-wrong-question/

Author Website – Getting Started http://www.darcypattison.com/marketing/author-website-getting-started/

Click here to Nominate Fiction Notes for a Top Blog for Writers

Thanks! It’s been a pleasure to talk with you this year!

December 7, 2015

Sell Your Novel: 2 Important Tools

You’ve finished your novel! Hurrah! Wahoo! Take time to celebrate!

And then, you wonder, can you sell this manuscript to a publisher? Welcome to the world of marketing your novel. It’s a relatively straight-forward process and two simple tools make it easy.

The Query Letter and the Synopsis

You can’t live long as a writer without developing a dread of The Query Letter. But it shouldn’t be a fearful thing.

First and foremost, a query is a business letter. You are asking a business (either agent or editor) a simple question. “Are you interested in reading my story?”

Please – don’t make it more difficult than that.

I know. Sometimes we’re tempted to endlessly critique a simple, one page query letter. Resist the urge. Write a business letter and let it do its job.

Here’s a simple plan:

Paragraph 1: Simple statement of what you’re selling. State what you have to sell. You should mention the title, length, genre and anything else pertinent. If you have a particular reason to sell to this particular agent/editor, state it here, too.

Paragraph 2: Hook the reader. Why should a reader care about your story? You’re a writer. In fact, you’re a great fiction writer. Just write a simple one-paragraph hook for the novel. Answer the “So what?” question and make the reader want more. That’s the key: you want the agent/editor to want to read much, much more!

Paragraph 3: Who are you? Here’s where you insert the simple 100-word bio that you’ve already got set up somewhere. Tweak it to make it fit this novel, of course.

Streamline Marketing with a Grab File of Previously Written Bios and Summaries

I like to take time to write up bios and summaries of stories in various lengths and then just customize the bio/summary for any given situation. Here’s a few of the bios I have available::

Tag line: Darcy Pattison, children’s book author and writing teacher, . . .

25 word bio: Include the most prestigious awards/publications/etc. If you have none, do NOT apologize or say, “I’m not published yet, but. . .” Just don’t say anything.

50 word bio: Here, I build on the previous and add any other books/awards that are appropriate.

100 word bio: Building on the previous, I loosen up some and try to add some fun and more details.

Full Blown bio for when I’m speaking: Usually, I only need a full blown bio for when I’m speaking and they want to introduce me. Or teachers/librarians/reviewers/etc. sometimes want a full bibliography. For those times, I keep a pdf version available for download.

Synopsis

I’ve just written a synopsis and it was frustrating. I took 60,000 words to tell a story and a synopsis attempts to tell the story in only 1500-2000 words. Obviously, you’re going to leave out tons of story! How do you manage it?

The best advice I’ve heard is to tell the main through-story as if it were a short story. The through-line is the main plot or the story that carries throughout the story. It’s like a line is anchored in chapter one and then threads through every part of the story.

My first thought was to summarize every chapter with a sentence or two, but that’s not quite right. Instead, think short story. It needs to read as an interesting story, but you have few of the tools usually used in short stories. There’s little room for dialogue or in-depth scenes. You may hint at a scene here or there, but you won’t really develop it. Instead, the synopsis is narrative writing. Still use your strong verbs and sensory details whenever possible, but focus on moving through the story and keeping the reader wondering what comes next.

The query and synopsis aren’t hard. They are, however, a tighter form of writing than you’re used to while writing that long, long novel. Don’t agonize after them; just get them done and get the query out the door! Because we want to see your novel in print!

November 30, 2015

Rough Draft to Final Draft

NaNoWriMo is almost over, which means many of you will now 50,000+ words on a new draft.

Of course, you realize it’s a rough draft. So, what’s next?

Since 1999, I’ve taught Novel Revision Retreats that answer this very question. How do you take the rough draft to a finished draft?

Step 1. Look at what you’ve written. At this point, there are really two versions of your novel. There’s the novel in your head and the novel on the page. And they aren’t the same. Your intentions were only partly realized in this version. That means its time to actually look at what you wrote, and not what you think you wrote.

I ask writers to go through the mss chapter by chapter (or scene by scene, if they’d rather) and write one sentence to summarize the actions (plot) and another sentence to summarize the emotional content of the scene/chapter. Also, note whether the scene contains conflict.

If you read through these summaries, it should be a fairly smooth synopsis of the entire story. And you’ll see the holes in the story much easier.

Order the paperback now.

November 23, 2015

Turning Out Words: Productivity

My life is full. And I don’t want it any other way. I’m blessed to have such a rich, varied and full life.

But, oh! Life is full! And I need to get writing done.

I recently read a great book on productivity. Now, don’t let it scare you away, because it’s called, 2K to 10K: Writing Faster, Writing Better, and Writing More of What You Love by Rachel Aaron. It’s a $0.99 Kindle book, and it’s worth way more.

I recently read a great book on productivity. Now, don’t let it scare you away, because it’s called, 2K to 10K: Writing Faster, Writing Better, and Writing More of What You Love by Rachel Aaron. It’s a $0.99 Kindle book, and it’s worth way more.

Here’s why. Rachel Aaron chronicles her story of going from very low productivity to extremely high productivity. She has a three-pronged approach.

Knowledge. Before Aaron sits down to write, she knows what she’ll write. In other words, she does extensive pre-writing before she starts to write. This involves developing the world, the characters, and outlining the plot. Beyond that, on the day she writes a scene, she’ll spend 5-10 minutes sketching out the scene. To put it in my terms, she decides on the major beats of the scene. What are the major bits of action, dialogue, and thoughts that must happen in this scene and in what order should they come?

I always emphasize the importance of prewriting. When I teach writing to kids, I spend the biggest chunk of time on the prewriting phase, making sure they know WHAT to write about. If you want to improve your writing, learn the discipline of prewriting. Aaron says that this alone will double your word count on any given day.

Time. Next Aaron started to pay attention to her best working times. She realized that she needed four hours of uninterrupted time and it was best to write in the afternoons. In order to figure this out, she kept statistics. I know – words and numbers. But numbers are often important in our work. Over a period of time, Aaron recorded the start/stop times for writing and the number of words per session. After accumulating data, she analyzed it to find her most productive times. Once you know that, it’s simple. Protect that writing time and make sure your friends/family help you protect it.

Enthusiasm. Finally, Aaron realized that some days she was more enthusiastic about her work than others. In studying the problem, she realized that she wasn’t excited about some scenes. Well – if the AUTHOR isn’t excited by a scene, why should a reader be excited, she reasoned. Turning back to the prewriting phase, Aaron decided that she wouldn’t write a scene ever again unless she was excited by something in the scene. Some turn of phrase, turn of events, twist of emotions or something. If she couldn’t find that enthusiasm, she’d cut the scene and work to find another version of the events that did excite her.

By the end, Aaron was writing 10,000 words/day – regularly. Prewrite. Write at your most productive times (and you only know that with data). And get and stay excited about your story. It’s easy!

I started my new novel today and wrote 1750 words! Far from Aaron’s 10,000 words/day, but I’m just getting started! She says that she also speeds up as the novel enters the last phase. it was a blast to write today because I was so excited to get started – with a new set of strategies that might actually push me to write faster – and better!

November 16, 2015

EBooks for Kids? New Study Says Maybe Not

To study ebook adoption by kids and school libraries, School Library Journal and Follett School Solutions recently released the Sixth Annual Survey of Ebook Usage in the U.S. School (K-12) Libraries (September 2015).

Optimism about ebook adoption in schools has run high for the last few years, but this study provides some interesting news. Depending on where you fall on the issue – pro-eBook or pro-printBook – the details are shifting.

Reading on eBooks May Hamper Learning. In the past year, several research studies report that reading on ebooks may hamper understanding and/or retention of information, especially putting events into a time order. However, the studies come with a big question mark: “what about ‘ebook’ or mobile-device natives?” Kids growing up today who have known only computers and smart phones may develop differently – the research is still out.

Reading on eBooks May Hamper Learning. In the past year, several research studies report that reading on ebooks may hamper understanding and/or retention of information, especially putting events into a time order. However, the studies come with a big question mark: “what about ‘ebook’ or mobile-device natives?” Kids growing up today who have known only computers and smart phones may develop differently – the research is still out.

USABILITY PROBLEMS: Too Many Standards, Too Many Passwords. Students and school libraries have too many conflicting choices for reading an ebook. On Kindle alone, there are eight different devices and apps for another 27 devices. If a school library tries to commit to one device, say Kindle or Nook, the rapidly changing landscape means their ebook collection could rapidly become out-dated and unusable. Education distributors work around this by providing browser-based ebook readers (again, they are proprietary) that can be accessed by any device with a browser. Even getting around the problem of devices, students then have to contend with accounts and passwords. Digital security demands that schools maintain strict control of access to the ebooks. In my opinion, this is the biggest factor limiting the wide-spread adoption of ebooks in schools. The answer, of course, is for companies to stop haggling over their proprietary devices and strictly adhere to the international ePub3.0 standards. That’s unlikely.

In the short term, the companies may feel it’s imperative to slug it out over the best platform for delivering and reading ebooks. In the long run, I think they are hurting themselves by alienating students and school staff. If it continues for long, educators may decide it’s not worth it and turn back to only print resources.

eBooks are Available in Schools. Across the US, about 56% of schools report that ebooks are available. But students don’t often choose them (see standards/passwords above for at least a partial explanation). Nonfiction related to school projects edges out fiction titles in popularity. Only 6% of schools report a high interest in ebooks, 37% report moderate interest, and 57% report low or no interest. Availability doesn’t equal use. Kids aren’t feeling the love for ebooks!

Parents Demand Technology. Interestingly, it’s often parents who demand technology in the classroom. Over 20% of schools have a one-to-one device policy, which means that each child has a device for at least part of a day; another 24% plan to add one-to-one soon. But the problems are massive, from funding to implementation (see the standards/passwords above). While this study doesn’t cover parental or students attitudes toward ebooks, the Scholastic 2015 Kids and Parents Reading Report says that 65% of kids say they’ll always want to read print, up from 60% in 2012. Teenagers tend to read more when introduced to ebooks; on it’s top 12 list of things parents can do to encourage more reading, providing more ebooks holds the number 12 position. Read the Scholastic report for more details on the parent’s views on ebook reading.

Are your books available as ebooks? Do you read more print or ebooks? Do your kids/grandkids read more print or ebooks?

November 9, 2015

Revision Mindsets: Artist, Story or Audience

I talk a lot about revising fiction here and when I visit with people. I teach novel revision, especially in my novel revision retreat. Recently, I’ve been trying to reconcile the different ways talk about revision and understand the differences. It seems to me that there are several distinct differences, each with its own strengths.

Three distinct mindsets about revising. Which one do you use?

Three distinct mindsets about revising. Which one do you use?Don���t Revise. One school of thought is that the raw energy of a first draft represents your storytelling at its best. For these writers, they will work on learning craft issues, but once a tory is written, they don���t want to revise extensively, or they feel it will kill the energy. Don���t��� mistake this for laziness; they are diligently learning plotting, characterization, and so forth. Rather, like other artists, they believe the raw energy ��� a sort of primitiveness in visual art might be an analogy ��� is more important.

Re-envision. This type of revision takes a first draft and re-envisions it drastically to meet a mental model of a perfect story. The ideal story varies from writer to writer and genre to genre. Some will tout the hero���s journey as the perfect story, and scenes must slot into the stages of the journey. Whatever the story model, the goal is to match up the current story with the model. Often, it requires extensive rewriting because the writer���s first draft didn���t follow the model.

While this holds out the promise of a great story, it can also be a trap for the under-confident writer. If an editor has a different mental model of story, it could mean extensive rewrites of a story that under a different editor would be acceptable.

Reader Oriented. For me, the first draft of a story is to find out what story you want to tell. All subsequent drafts have the goal of finding the most dramatic way to tell the story. That means, you���re thinking of the reader. How can you tell a story to impact the reader the way you want? Do you want them to be scared, touched emotionally by tenderness, or so tense that the pages turn themselves? Revision here blends the mental model of a story with the reader���s imagined responses.

Of course, literary theorists can talk about reader-response theory, the narrative arc, and lots of other literary analysis techniques. I���m not saying you need to be proficient in all of those. Rather, I���m asking ��� what���s the most important consideration for you as you revise?

Your unique vision ��� you, as a creative artist.

Shaping a story to match your mental model of Story (with a capital S). Story theory.

Reader���s reaction. Audience.

No rights and wrongs. Only a recognition of your goals as a writer.

What’s your mindset as you approach the revision of a story? And does it change from story to story?

October 26, 2015

Does Your Scene Pivot: Creating Turning Points

I’m revising my WIP novel one scene at a time and finding places where I need to do lots of work. Specifically, I want scenes that pivot.

A scene is self-contained section of the story. Characters come into a scene with a goal and they either reach their goal or not. The scene should have a beginning, middle and end. And, according to THE SCENE BOOK by Sandra Scofield, your scene also needs a pivot point.

Scofield says that characters go into a scene with a goal, with something they are fighting for. But at some point the story twists, deepens, or changes in a fundamental way.

If you don’t have one, the scene is boring. Think about where the scene’s essence lies: the point at which everything changes. There if Before X and After X. X is the focal point. – Sandra Scofield, p. 54, The Scene Book

It’s a hard concept in some ways to talk about, but you know it when you see it. In this short scene from the movie,”Good Will Hunting,” the focal point, pivot point, hot spot, turning point, or apex is when Will steps in to help his friend. This is a great example because it shows the character in action, doing something that matters.

If you can’t see this video, click here.

By contrast, some scenes in my WIP just sit on the page. For example, I have one scene where the main character meets the romantic interest character. There’s a lot of characterization going on; they are at a coffee shop where she’s a barista and he’s ordering a special coffee drink; there’s some humor. But the scene still felt flat. Until I realized that there’s no real pivot point, no fulcrum for the scene. To change it, he asks a simple question, “Who are you?” That launches her into a humorous, but character-revealing pseudo-tirade, which results in him really paying attention to her and finding that he’s VERY attracted. Before the tirade, he’s not interested; after the tirade; he’s hooked.

To revise your scenes, fill in the blanks:

Before _____________(Pivot Point), my character _______________; AFTER _______________(Pivot Point), my character ____________________.

Find a way to pivot somewhere in each scene–and you’ll hook me as a reader!