Roy Miller's Blog, page 233

March 28, 2017

3 Tips for Navigating the April PAD Challenge

Last week, I posted the guidelines for the 2017 April PAD Challenge, which will start at the end of this week. This will be my 10th time through, so I thought Iâd share some tips on how to get through a month of daily poeming.

*****

Revision doesnât have to be a choreâsomething that should be done after the excitement of composing the first draft. Rather, itâs an extension of the creation process!

In the 48-minute tutorial video Re-creating Poetry: How to Revise Poems, poets will be inspired with several ways to re-create their poems with the help of seven revision filters that they can turn to again and again.

*****

Consider Different Approaches

For each prompt, thereâs a new poem to write. In fact, several poets over the years have shown there are often dozens of poems they can write from just one dayâs prompt. So the first thing I like to do after encountering a new prompt is to consider different approaches I could take for the prompt.

For instance, the prompt might be to write a scary poem. Of course, I could write a straight up scary poem, and that would be fine. But itâs possible to write a humorous poem that includes horror elements. Or write a poem thatâs scary, but maybe not in the traditional sense of zombies, vampires, or killer clowns. Instead, it might be food safety or a strange phobia.

Outside of considering different subject approaches, I also like to consider form for a moment. Do I want to write a poem that rhymes? Or would I rather go all free verse (or even prose) and figure out structure later? Sometimes when Iâm not sure, Iâll just pick a traditional poetic form and use the constraints of the form to help me figure out which direction to take my poem.

Just Write

I like to take a minute or three to consider different approaches, because Iâm a busy guy. After that, I just write. No worrying about publication, what everyoneâs going to think when they open the dayâs prompt and poem example, or really anything other than writing until the first draft is done.

For me, the goal is not to write a Best American Poem each time I sit down; itâs merely to create and see where that takes me. Often, I come to a poem with certain ideas and through the process of creating I find myself somewhere new. And itâs not unusual for those first drafts to kick me into a new poem thatâs going somewhere else completely.

I firmly believe that poems beget poems. So donât worry about being perfect; just write!

Have Fun

And yes, have fun. Let me say it again: Have fun!

If you miss a day or three of the challenge, thatâs fine. Donât stress out. If your poem isnât highlighted as a top poem of the month, thatâs fine. Hundreds (if not thousands) of poems written specifically for the April PAD Challenge have been published over the past 9 years; not all of them were named top poems of the month.

Instead of stressing over that stuff, seriously, just have fun. Write. Create. Experiment. Enjoy the process of writing and writing with others who are enjoying the process of writing.

One last time: Have fun!

*****

Robert Lee Brewer is Senior Content Editor of the Writerâs Digest Writing Community and author of Solving the Worldâs Problems (Press 53). Heâs a featured poet at the 2017 Austin International Poetry Festival (April 6-9) and is about to start his 10th year of prompting poets to poem on Poetic Asides beginning on Saturday morning.

Follow him on Twitter @RobertLeeBrewer.

*****

Find more poetic posts here:

Â

Save

You might also like:

The post 3 Tips for Navigating the April PAD Challenge appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Chris Colfer: The First Time I Braved New York (and a Taxi!)

âYouâre going to New York City ⦠by yourself?â my mom was shocked to learn. âBut Christopher, youâve never even been to the doctor by yourself.â

Continue reading the main story

âMom, life is about stepping outside your comfort zone,â I replied â or maybe I said: âCut the umbilical cord, Mrs. Bates! Iâm going to see my friends!â I canât remember.

I fully expected Lea or Jenna would greet me when I arrived at Kennedy International Airport â but I quickly learned thatâs not how it worked in a big city in 2008. Getting into the taxi of a complete stranger was the most terrifying experience of my life up to that point. I was convinced that I would be whisked away and murdered like one of the victims in âThe Bone Collector.â I was too afraid to look my driver in the eye or try pronouncing his foreign name (it was Gerald, by the way). The taxiâs door locks were broken and clicked loudly whenever the vehicle accelerated, so naturally, I thought gangsters were shooting at us.

Photo

Mr. Colfer on his first visit to New York.

Suddenly, everything changed as the Manhattan skyline came into view. My fears of being murdered faded away and were replaced with a wave of wonder. I couldnât breathe, I couldnât think, I couldnât feel â all I could do was stare in bewilderment at the towering buildings in the distance. I had seen âThe Wizard of Ozâ a million times, but until that moment on the bridge, I never knew how Dorothy felt when seeing the Emerald City. It was as bittersweet as it was magical, because I knew Iâd never see New York for the first time again.

Continue reading the main story

At 3 in the morning on my first night, a garbage truck rumbled down the narrow street outside and rattled the whole building. I leapt from a deep slumber on the couch and ran into the kitchen. After some reassurance, the girls tucked me back in, but I couldnât sleep another wink.

My mission for the week was to see as many Broadway shows as possible. My first New York theater experience was a preview of âShrek the Musical,â and boy, did all the families from the Midwest and I love it! I also saw âGypsy,â with Patti LuPone; âHairspray,â with Harvey Fierstein and Marissa Jaret Winokur; âMary Poppinsâ; âAvenue Qâ; and âSpring Awakeningâ three times. But nothing compared with the musical number in âShrekâ when Sutton Foster tap danced with the rats. It just tickled me.

Jenna was still in âSpring Awakeningâ during my visit, so I spent a lot of time backstage at the Eugene OâNeill Theater with her fellow cast members. Playing it cool and pretending I didnât know every detail about their personal lives and theater credits was my best performance to date. When I wasnât being a creepy groupie, Jenna would kindly walk me to the theater of my selected performance before her call time, drop me off and then pick me up after our shows. It was the closest thing to adult day care I hope to ever experience.

Continue reading the main story

The night I saw âHairspray,â however, disaster struck! When the show was over, Jenna texted me and asked if I could catch a cab and meet her back at the apartment. My palms became clammy at the very thought of hailing a taxi on my own. The task was nearly impossible as all the shows in the theater district were letting out at that exact same time. I finally managed to snag a cab, but it was swiped by a stealth family in foam Lady Liberty crowns.

Just as I worried Iâd be stranded in Times Square forever, I was hit by what I thought was a stroke of total genius. I sneaked inside a hotel lobby, hid in the bathroom for 45 minutes, pretended to be a guest as I re-emerged, and had the doorman hail me a cab. I was so relieved, I tipped him 15 bucks.

Continue reading the main story

As I rode back to Lea and Jennaâs apartment that night, I was beaming with more pride than I had ever felt. Apparently the cruel streets of New York City were no match for the cunning farm boy from Clovis.

âWell, how was New York?â my mom asked later as she sprayed my shoes and luggage with Lysol.

I told her how the Bone Collector had driven me into the city, how I was awakened by a deafening garbage truck, how I had braved the crowded theaters on Broadway, and how I had conned my way into a cab after a taxi was taken from me at knife point. Admittedly, I may have exaggerated a few things.

Continue reading the main story

âOh my,â she said. âI guess you wonât be going back to New York City anytime soon.â

âWhat are you talking about?â I said. âIt was amazing!â

Continue reading the main story

The post Chris Colfer: The First Time I Braved New York (and a Taxi!) appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Julio Cortázar Teaches a Class on His Own Short Story

The following is from Literature Class, a collection of eight lectures Julio Cortázar delivered at Berkeley in 1980. Translated by Katherine Silver.

We are all punctual to an exasperating degree; itâs exactly two oâclock. Iâm not sure, but I think the custom is to start a little late in case people arrive late, so we can wait a little.

To start off Iâd like to talk about something here that has delighted me. Throughout the time weâve been in contact, besides one-on-one conversations with many of you and some casual encounters, Iâve received a number of letters, some of which contain questions; others express a point of view about something I might have said here. This is very touching, and I want to publicly express my gratitude, because itâs a sign of trust in me and above all, a sign of friendship. Every single one of those letters has a purpose, points to a path or sometimes asks questions about one. I donât want to ignore this because it feels to me like an immediate continuation of what is happening here among us once a week that then continues on other levels. Itâs very beautiful to me, and in any case very useful, because it allows me to see into some of your personal worlds and to live and feel more fully what I have come here to say.

In some of the letters there are also critiques, and perhaps those are the best. Iâd like to clarify one thing that is the source of a very friendly and polite critique I received in a letter from someone. It was about something I had said about fantasy and the imagination in response to a question. It seems I didnât respond with sufficient breadth, and probably not with sufficient clarity. The person who wrote me that letter thought that I tended to see a writerâs fantasy and imagination as somewhat secondary, an accessory. I have the impression that those of you who have listened to all my previous classes must thinkââââas I doââââthat itâs exactly the contrary. I believe that a fiction writerâs most basic weapon is not his subject matter, not even how he writes about it, whether better or worse, but rather that capacity, that way of being that determines his devotion to fiction rather than, say, chemistry; this is the basic, dominant element in any literature throughout the history of humanity.

Article continues after advertisement

I use the word fantasy as a general term; within fantasy we can include everything that is imaginary, fantastic, and we have discussed this a lot during these talks .â.â. I donât think I need to elaborate further, you all know very well how important it is, not only for what I have written but also for what I personally prefer in literature. What I wanted to sayââââand perhaps this is the reason for the misunderstandingââââand what I will repeat now perhaps more clearly, is that at this time, above all, and very especially in Latin America considering the current circumstances, I never accept the kind of fantasy, the kind of fiction or imagination, that spins around itself and only itself, where you feel that the writer is creating a work of only fantasy and imagination, one that deliberately escapes from the reality that surrounds and confronts him and asks him to engage with it, have a dialogue with it in his books. Fantasyââââthe fantastic, the imagination that I love so dearly and that Iâve used to try to construct my own workââââis everything that helps to expose more clearly and more powerfully the reality that surrounds us. I said so at the beginning and I repeat it now as we leave the realm of the fantastic and enter realism, or what is called realism. Iâve now clarified something that I think is important because it would never occur to me to diminish the importance of everything that is fantasy for a writer, for I still believe it is a writerâs most powerful weapon, the one that finally opens doors onto a much richer and often more beautiful reality.

Iâve written several stories in which I think this is shown and exemplified perfectly, stories like âThe Southern Expressway.â There are others I could name that have unusual elements with no value in and of themselves, no independent importance, but they are signals, pointers, used to increase the sensation of the reality of the action, the plot. For this reason, I would like us to spend a little time with one of those stories, which I wrote about six years ago and is called âApocalypse at Solentiname.â Itâs one of the most realistic short stories imaginable because itâs based almost entirely on something I experienced, something that happened to me, that I tried to write about with as much fidelity and clarity as possible. At the end of that story, there appears a totally fantastic element, but itâs not an escape from reality; on the contrary, itâs a little like carrying things to their ultimate consequences so that what I want to express in a way that reaches readers more powerfully, which is a Latin American vision of our times, explodes in their faces and obliges them to feel implicated and present in the story.

Since itâs not very long, Iâve decided to read it because I think this is more valuable than any extraneous explanation I could give. I want to clarify one or two things of a technical nature before reading it, to avoid any difficulties. As you know, the people of Costa Rica are called ticos, and the people of Nicaragua are called nicas: ticos and nicas are mentioned a few times. Toward the end thereâs reference to a great poet and great resistance fighter from Latin America named Roque Dalton, a Salvadoran poet who fought for many years for what a large part of the Salvadoran people are fighting for right now, and he died under dark and painful circumstances that one day will be revealed, but we still donât have enough information about it. Thereâs mention of Roque Dalton, whom I loved very dearly as a writer and a comrade in many things.

The storyââââIâll say this again so itâs very clearââââis absolutely true to the events it recounts, except what happens at the end. Iâll also explainââââI guess you all know thisââââthat Solentiname is the name of a community that the Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal ran for many years on one of the islands in Lake Nicaragua, a community I visited under the circumstances recounted here and that was then destroyed by Somozaâs National Guard before the last offensive that finished Somoza off. In that very impoverished community of fishermen and peasants, which Cardenal led spiritually, very great artistic and intellectual work was carried out among the mostly illiterate and disadvantaged. Ernesto Cardenalââââby the wayââââtold me the last time we talked that he intends to build his community again now that Nicaragua is free and thereâs the possibility of doing that. I hope he goes through with it, because the work he did in that community for yearsââââwhile being hounded, persecuted, and threatened all the timeââââis one of those efforts that gives me more and more hope and faith in our people.

Apocalypse at Solentiname

Thatâs just how ticos are, quiet but full of surprises, you land in San José, Costa Rica, and there waiting for you are Carmen Naranjo and Samuel Rovinski and Sergio RamÃrez (whoâs from Nicaragua and not a tico but whatâs the real difference anyway itâs all the same, whatâs the difference in me being Argentine, though out of politeness I should call myself tino and the others nicas or ticos). It was so hot and even worse, everything started right away, the usual press conference, why donât you live in your country? Why was the movie Blow-Up so different from your story? Do you think a writer has to be politically engaged? By now I know that my last interview will take place at the gates of hell and theyâll ask the same questions, and if by some chance itâs chez Saint Peter, nothing will change, donât you think that down there you wrote too hermetically for the common folks?

Then on to Hotel Europa and the shower that crowns a trip with a long monologue of soap and silence. Except that at seven oâclock when it was finally time to take a walk through San José and find out if it was as modest and uniform as Iâd been told, a hand grabbed my coat and behind it was Ernesto Cardenal, and what a hug, poet, so glad youâre here after that conference in Rome, after so many times over the years weâve met on paper. It always surprises me, always touches me when someone like Ernesto comes to see me, to pick me up, you might say Iâm overflowing with false modesty but just come out with it, old man, the jackal howls but the bus still runs, Iâll always be an amateur, someone who looks up to certain people from way down below with so much love, and then one day it turns out those people love him back, these things are beyond me, but letâs change the subject.

The new subject was that Ernesto knew Iâd arrived in Costa Rica and, what do you know, he flew from his island because the little bird who brings him news told him that the ticas had planned for me to go to Solentiname and he found the idea of coming to get me irresistible, so two days later Sergio and Oscar and Ernesto and I crammed ourselves into the much too crammable cabin of a Piper Aztec aircraft, whose name will always remain a riddle to me but that flew with ominous hiccups and burps while the blond pilot played some countervailing calypsos and seemed completely nonchalant about my idea that the Aztec was carrying us straight to a pyramid to be sacrificed. That didnât happen, as you can see, we landed in Los Chiles and from there the equally wobbly jeep dropped us off at the country house of the poet José Coronel Urtecho, whom more people should read and in whose house we rested and talked about so many other poet friends, about Roque Dalton and about Gertrude Stein and about Carlos MartÃnez Rivas, until Luis Coronel arrived and we set out for Nicaragua in his jeep and in his launch that reached alarming speeds. But first there were keepsake pictures taken with one of those cameras that right then and there spits out a small piece of sky-blue paper that slowly and miraculously and polaroiderly starts filling up with gradual images, at first disturbing ectoplasms then little by little a nose, a tuft of hair, Ernestoâs smile with his Nazarene headband, Doña MarÃa and Don José outlined against the veranda. It seemed totally normal to them because they were used to using that camera, but I wasnât, for me seeing something emerge out of nothing, out of that little sky-blue square of nothing, those goodbye faces and smiles, filled me with wonder and I told them, I remember asking Oscar what would happen if after taking a family portrait the little sky-blue piece of paper started filling up out of nowhere

with Napoleon on his horse, and a roar of laughter from Don José Coronel, who as usual had been listening to everything, the jeep, come on, letâs drive to the lake.

We reached Solentiname as night was falling, there waiting for us were Teresa and William and a gringo poet and other people from the community; we went to bed almost immediately but not before I saw the paintings in a corner, Ernesto was talking with his people and he took the supplies and gifts heâd brought from San José out of a bag, somebody was sleeping in a hammock, and I saw the paintings in a corner and started to look at them. I donât remember who explained to me that they were painted by the peasants in that region, that one was painted by Vicente, this is Ramonaâs, some were signed and others werenât, but they were all so beautiful, once again a primal vision of the world, the clean gaze of someone who depicts their surroundings as a song of praise: dwarf cows in fields of poppies, sugar shacks people are pouring out of like ants, the green-eyed horse against a background of sugarcane, a church baptism that doesnât believe in perspective and trips and falls over itself, the lake with little boats like shoes, and in the background an enormous laughing fish with turquoise-colored lips. Then Ernesto came and explained to me that the sale of the paintings helped them carry on, in the morning heâd show me the work the peasants do in wood and stone and also his own sculptures; we were already nodding off but I kept looking through the pictures piled up in the corner, pulling out of the jumble of canvases cows and flowers and that mother with her two children on her lap, one in white and the other in red, under a sky so full of stars that the only cloud stood as if mortified in one corner, pressing against the frame, so afraid it had already scooted off the canvas.

The next day was Sunday and eleven oâclock Mass, a Solentiname Mass where the peasants and Ernesto and visiting friends discuss a chapter of the Gospels, which on that day was the arrest of Jesus in the garden, a subject the people of Solentiname discussed as if it were about them, the threat that they would be attacked at night or in the middle of the day, lives led in permanent uncertainty on the islands and on the mainland and everywhere in Nicaragua and not only in Nicaragua but almost everywhere in Latin America, a life surrounded by fear and death, life in Guatemala and life in El Salvador, life in Argentina and in Bolivia, life in Chile and in Santo Domingo, life in Paraguay, life in Brazil and in Colombia.

Later came thoughts about leaving, and it was then that I thought again about the paintings, I went to the community room and started to look at them under the dazzling noon light, the heightened colors, the acrylics and oils facing off against one another from horses and sunflowers and fiestas in the meadows and symmetrical palm groves. I remembered I had a roll of color film in my camera and I went out onto the veranda with an armful of pictures; Sergio, who had just arrived, helped me prop them up in the light, and one by one I carefully photographed them, centering each so it would fill the entire frame. Chance is sometimes like that: I had as many shots left as there were paintings, not a single one was left out, and when Ernesto came to tell us that the launch was ready I told him what Iâd done and he laughed, painting thief, image smuggler. Yes, I told him, Iâm taking all of them with me, Iâll project them onto my screen and theyâll be bigger and brighter than these, tough luck for you.

I returned to San José, went to Havana and hung around and did a few things there, then back to Paris, my fatigue so full of nostalgia, Claudine quietly waiting for me at Orly, once again the life of the wristwatch and merci monsieur, bonjour madame, committee meetings, films, red wine and Claudine, Mozart quartets and Claudine. Among all the things those tell-all suitcases had spewed out onto the bed and the rug, among the magazines, clippings, scarves, and books by Central American poets, were the grey plastic film canisters, so many over a two-month period, the sequence from the Lenin School in Havana, the streets of Trinidad, the silhouette of the Irazú volcano and its crater full of boiling green water where Samuel and Sarita and I imagined already roasted ducks floating in the sulfurous fumes. Claudine took the rolls of film to get them developed; one afternoon while walking through the Latin Quarter I remembered and since I had the ticket in my pocket I picked them up and there were eight. I immediately thought about the paintings from Solentiname and when I got home I opened the boxes and looked at the first slides in each group, I remembered that before taking pictures of the paintings I had shot the Mass with Ernesto, children playing among the palm trees just like in the paintings, children and palm trees and cows against a violently blue sky and a lake just a tiny bit greener, or maybe the other way around, I wasnât quite sure anymore. I put the slides of the children and the Mass in the tray, knowing that the paintings would come next and continue to the end of the roll.

Night was falling and I was alone, Claudine would come over after work to listen to music and spend the night; I set up the screen and poured myself a glass of rum with a lot of ice, the slide projector with its tray loaded and the button of its remote control; no reason to close the curtains, the obliging night was already there igniting the streetlamps and the perfume of the rum; it was so pleasant to think that everything would appear once again a little at a time, after the paintings from Solentiname I would show the rolls from Cuba, but why the paintings first, why that occupational hazard, art before life, and why not, that one asked this one in a continuation of their everlasting never-to-be-disassembled fraternal and spiteful dialogue, why not look at the paintings from Solentiname first, for they are also life, for itâs all the same.

First came the pictures of the Mass, pretty bad due to wrong exposures, the children, though, were playing in the bright light and such white teeth. I pushed the forward button without much enthusiasm, I could have kept looking for a long time at each slide so laden with memories, that small fragile world of Solentiname surrounded by water and henchmen, surrounded like the boy I was looking at without understanding, Iâd pressed the button and the boy was there against a very clear background, his broad smooth face of surprised disbelief as his body pitched forward, the neat hole right in the middle of his forehead, the officerâs pistol still indicating the path of the bullet, the others on either side with their machine guns, a jumble of houses and trees behind.

Whatever you think, it always gets there first and leaves you so far behind; stupidly I told myself theyâd made a mistake at the photo shop, theyâd given me another customerâs slides; but then the Mass, the children playing in the meadow, so how? Nor did my hand obey when it pressed the button and there was an endless saltpeter field at noon with two or three lean-tos built of rusty sheet metal, a crowd of people on the left looking at the bodies lying face up, their arms spread wide against a gray and naked sky; you had to look very closely to make out the group of soldiers walking away in the background, the jeep waiting at the top of the hill.

I know I kept going; faced with this that defied all sanity the only thing possible was to keep pushing the button, seeing the corner of Corrientes and San MartÃn streets in Buenos Aires and the black car with the four men aiming at the sidewalk where somebody wearing a white shirt and tennis shoes was running, two women trying to take shelter behind a parked truck, someone staring straight ahead, an expression of horrified disbelief, bringing his hand to his chin as if to touch himself and feel that he is still alive, and suddenly an almost dark room, dirty light falling from the tall latticed windows, the table with the naked girl supine and her hair falling all the way to the ground, the shadow with its back to the camera sticking a wire between her open legs, two men facing the camera talking to each other, a blue tie and a green pullover. I never found out if I kept pushing the button or not, I saw a clearing in the jungle, in the foreground a hut with a thatched roof and trees, up against the trunk of the closest one a thin man looking to his left at a disorderly group of five or six people standing very close together pointing machine guns and pistols at him; the man with the thin face and a lock of hair falling over his brown forehead looked at them, one hand half raised, the other possibly in his pants pocket, it was as if he were telling them something calmly, almost offhandedly, and even though the picture was blurry I felt and I knew and I saw that he was Roque Dalton, and so I pressed the button as if by doing so I could save him from the infamy of that particular death, and then I saw a car exploding right in the middle of a city that could be Buenos Aires or São Paulo, I kept pushing and pushing past flashes of bloody faces and pieces of bodies and woman and children running down a Bolivian or a Guatemalan hillside, suddenly the screen filled with mercury and nothing and Claudine entering quietly, her shadow filling the screen as she leaned over to kiss my hair and ask me if they were lovely, if I was happy with the photographs, if I wanted to show them to her.

I pushed the tray and started it from the beginning, you canât know how or why you do things once youâve passed a boundary you also donât know. Not looking at her, because she would have understood or simply been frightened by how my face must have looked; not explaining anything because everything was one big knot from my throat to my toenails, I got up and slowly sat her down in my armchair, and I must have said something about going to get her a drink and that she should have a look, she should have a look while I went to get her a drink. In the bathroom I think I vomited, or maybe I only cried and later vomited, or I didnât do anything and just sat on the rim of the bathtub letting time pass until I could make it to the kitchen and prepare Claudineâs favorite drink, fill it with ice and then hear the silence, realize that Claudine was neither shouting nor running to question me, only the silence and for moments that saccharine bolero from the apartment next door. I donât know how long it took me to get from the kitchen to the living room, to see the back of the screen when she reached the end and the room filled with the sudden reflection of the mercury and then the semi-darkness, Claudine turning off the projector and leaning back in her armchair and picking up her glass and smiling at me slowly, happy and sexy and so pleased.

âThey turned out beautifully, that one of the smiling fish and the mother with her two children and the little cows in the field; wait, and that other one of the baptism in the church, who painted them, tell me, I couldnât see the signatures.â

Sitting on the floor, without looking at her, I picked up my glass and drank it all down. I wasnât going to say anything, what could I tell her now, but I remember I vaguely considered asking her a stupid question, asking her if she had at some point seen a picture of Napoleon on horseback. But I didnât, of course.

I think that in a story of this kind the sudden appearance of an entirely uncanny elementââââentirely and decisively fantasticââââmakes reality more real and brings the reader something that, if stated explicitly or recounted in detail, would have ended up being one more report about all the many things that are going on, but within the story it is shown strongly enough, through the mechanism of the story itself.

I think that right now, before continuing, some of you might like to ask me some questions. I see one person there wants to.

Student: Would you mind talking a little about Roque Dalton? I think there are a lot of people who donât know who he is.

Yes, of course. Roque Dalton said he was the grandson of the pirate Dalton, an Englishman or North American who ravaged the coasts of Central America and conquered land he later lost. He also conquered, for better or for worse, some Salvadoran women from whom Roqueâs family descended, and they kept the name Dalton. I never knew, nor did Roqueâs friends, if that was true or one of the many inventions of his extremely fertile imagination. Roque is for me the very rare example of a man whose literary ability, whose poetic ability, was there from a very early age, mixed with or alongside a profound sense of belonging to his own people, their history and destiny. Never, from the age of 18, did he make a distinction between the poet and the fighter, the novelist and the combatant, and thatâs why his life was a continuous series of persecutions, prisons, exiles, escapesââââin some cases, spectacularââââand a final return to his country after many years spent in exile, there to join the struggle in which he would lose his life. Fortunately for us, Roque Dalton left a vast oeuvre: several volumes of poetry and a novel with a title that is both ironic and tender; itâs called The Poor Little Poet I Once Was. Itâs the story of a man who at a certain point feels tempted to devote himself fully to literature and leave behind all other things that his nature demands of him. In the end, he doesnât do that, and he continues to maintain the balance that I always admired in him. Roque Dalton was a man who at 40Â gave the impression of being a 19-year-old kid. There was something very childlike about him, heâd act like a child, he was mischievous and playful. It was difficult to see, to realize, the power, the seriousness, and the effectiveness that was hidden in that man.

I remember one night in Havana, a group of foreigners and Cubans gathered to talk to Fidel Castro. It was in 1962, at the beginning of the Revolution. The meeting was supposed to start at ten at night and last an hour, and it lasted until exactly six in the morning, which almost always happens in these meetings with Fidel Castro, which go on and on endlessly because he never gets tired and neither do his interlocutors under those circumstances. Iâll never forget how, around dawn, when I was already dozing off because I couldnât fight my fatigue and exhaustion .â.â. I remember Roque Daltonââââvery skinny and not very tallââââstanding with Fidelââââwhoâs not skinny at all and is very tallââââand stubbornly discussing the proper use of a certain kind of gun, I never found out which one exactly, some kind of machine gun. Each was trying to convince the other that he was right, with all kinds of arguments and even physical demonstrations: they threw themselves down on the floor, then jumped back up .â.â. all kinds of bellicose antics, which left us all pretty amazed.

Thatâs how Roque was: he could play while talking seriously. Obviously the topic interested him for reasons that had to do with El Salvador, and at the same time it was all a big game that amused him deeply. His booksââââthe poetry as well as the prose, he also has a lot of essays, many political works .â.â. they cover an important period in our history, especially the decade from â58 to â68. His analyses are always passionate but at the same time lucid, his denunciations and arguments always have strong historical foundations. He wasnât a propagandist; he was a thinking man and behind and in front and underneath all that was always a great poet, a man who has given us some of the most beautiful poems Iâve read in the last 20Â years. Thatâs what I have to say about Roque, and I hope you read him and get to know him better.

Student: In the story, you mention that people are afraidââââlike Jesusââââof being betrayed, but donât you think this is, generally speaking, because in Latin America reality is seen in a fantastic, emotional, irrational way, and only from one point of view? Because you talk about the people who were killed by the military, but in Argentina soldiers have also been killed, for example, Aramburu. Itâs always looked at from only one point of view and thatâs why there are those constant struggles, instead of trying to find a rational solution.

Of course there are constant struggles; of course there have been and continue to be confrontations, as there have been constantly in Nicaragua, and as there are right now in El Salvador. Of course there is violence on both sides and in many cases the violence is unjustifiable, on both sides of the struggle. What I think we have to consider and always keep in mind when we talk about violence, confrontations, and even criminal acts between two opposing forces is why did the violence start and who started it, or rather we need to introduce a moral dimension into the discussion. The Brazilian bishop or cardinal Hélder Câmara (I think he was a bishop) and the archbishop of El Salvador, Monsignor Romero (brutally assassinated a few months ago), both men of the church, they said in their last speeches that an oppressed, subjugated, murdered, and tortured people has the moral right to take up arms against their oppressors, and I think they were putting their fingers on the very core of the problem; because itâs very easy to be against violence in general, but what is often not considered is how that violence came about, what process originally unleashed it.

To respond very concretely to your question, I am fully aware that in my country, in our country, the forces that rose up against the army and the Argentine oligarchy committed many acts that we can qualify as excessive. They have behaved in ways that I cannot personally condone, or accept, not at all, but still, within that moral condemnation, I am aware that they would never have reached that pointââââbecause they wouldnât have needed toââââif beforehand, with the previous dictatorships (Iâm talking concretely about Generals OnganÃa, Levingston, and Lanusse), there hadnât been a monstrous escalation of torture, violence, and oppression, which finally led to the first uprisings against them. This is not a class about politics and I will stop here, though I think that you and I could discuss this topic much more, because clearly we are very familiar with it as Argentines. But I think Iâve said enough to show my opinion on this point.

Â

Reprinted from Literature Class with permission from New Directions.Â

The post Julio Cortázar Teaches a Class on His Own Short Story appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Romance Short Story: âLadybugâ by Gail Bartley

âLadybugâ by Gail Bartley is the First Place-winning story in the romance category of the 12th Annual Writerâs Digest Popular Fiction Awards. For complete coverage of this yearâs awards, including an exclusive interview with the Grand Prize winner and a complete list of winners, check out the May/June 2017 issue of Writerâs Digest. And click here for more information about entering the 13th Annual Popular Fiction Awards.

In this bonus online exclusive, you can read Bartleyâs winning entry.

âLadybugâ by Gail Bartley

Ladybug isnât really an insect, despite what her four-year fans believe. She earns her modest living starring in The Bug Parade, a one-woman extravaganza of fantastical creatures she creates herself in a cavernous loft, far out in Willamsburg, Brooklyn. It is not yet the trendy neighborhood it will one day become. She has an erratic frizz of brunette curls, a ballerinaâs body, and is given to random acts of hugging. Itâs rumored that she sleeps around, in a wholesome, Kundalini and carrot juice sort of way. No one really knows if this is true, for in spite of all the hugging, Ladybug isnât an easy read.

Self-contained as an actual ladybug, standing alone on the corner of 73rd and Madison, she loads her heavy case of costumes into a Yellow Cab which speeds off into the milky grey light of another winter Saturday. On the private pre-school, Upper Eastside birthday-party- circuit, The Bug Parade is in great demand. Ladybug often works these parties back-to-back, sometimes three in a day, until itâs all one sugary, Baby Gap blur.

Sliding into the cab, she tucks her purse neatly on her lap, exactly the way her mother does; the way all her sisters do, another vestige of her formerly-small-town-Ohio self which she cannot shake, no matter how far she runs. Inside the purse is an untouched chocolate truffle cake baked inside a red clay flower pot, the whimsy of which was lost on the three-year old guests at the last party.

That night, after a long hot shower, Ladybug crawls into bed with the flower pot cake and a fork, thinking of the Balloon Guy, whoâd slipped her this treat on the guest floor of the Feinmanâs townhouse where the two of them were taking a break from the toddlers. The Balloon Guy (whose real name is Max) is the Michelangelo of balloon animals. Heâs been flown to Paris at least twice to entertain at fancy parties and recently spent a whole month in Tokyo, wowing customers at an exclusive childrenâs toy store.

While Max glows with confidence when creating balloon animals, he is otherwise shy, most especially around Ladybug, for whom he feels a heart-thumping attraction. Offering her pilfered cakes is the safest way he can think of to signal his affection.

A few days later, Ladybug steps out of H & H Plastics on Canal Street with a waggling armful of the foam rubber she uses to build her costumes and sees Max at one of the outdoor stands which line the street, selling everything from socks to sunglasses. She barely recognizes him at first, having never seen his naked head minus the silk top hat he wears when making balloon-animal magic. Maxâs hair (as uncontrollable as her own) sticks up in five or six different directions, clearly not a style but a more of situation best resolved by hats.

Caught off guard by this unexpected Max-sighting, Ladybug is torn between making a quick getaway before he spots her or just walking up like a normal person and saying hello, but before she can make up her mind, Max sees her and waves.

Watching Ladybug approach, Max (whoâs been picking through a pile of tin wind-up toys) nervously tosses a miniature robot from hand to hand while the vendor glares at him from behind a mountain of folding umbrellas.

âI thought that was you,â says Ladybug. She stands a few feet away since sheâs a walking hazard with all the foam rubber. She waits while Max searches for his wallet to buy the toy from the vendor, who charges him ten dollars out of spite. Right then, it starts to pour.

Max reaches for Ladybugâs arm and pulls her gently under the storeâs awning. The vendor shakes his head, amazed at someone who will spend ten bucks on a fifty-cent toy when what he clearly needs is a three-dollar umbrella. But Max simply isnât an umbrella-person, and neither, it happens, is Ladybug. In spite of a nagging sense of missing something when caught in the rain, they have never been prone to solve the problem with the purchase of an actual umbrella, especially when standing next to a stack of them so large it shelters two people quite nicely from a downpour.

Besides, Max and Ladybug are consumed with something more important than precipitation. Fate has thrust them together at this particular umbrella-and-toy stand, of all the countless umbrella-and-toy stands from Hoboken to Harlem, a fact they both know must be acknowledged. Thus, when a short while later, Ladybug finds herself riding the subway home to Brooklyn with Max at her side, her bug-parts balanced gallantly on his lap, she is nervous, happy, and alarmed. For it is Ladybugâs tendency to fall into bed with men following innocently chance encounters like this one, and generally, to regret it.

The sweet promise of a glance across a library shelf or a shared ride up a long escalator seemed to fall apart once the breathing slowed, the strange bathroom was peed in and Iâll-call- you was said, if rarely meant. What could have been, mostly never was. The last one, sheâd thought, might be different. Theyâd shared every single Wednesday for an entire year, but only Wednesdays, never more. So when Mr. Wednesday suddenly stopped calling, thirteen months ago, Ladybug took the hole in her week that was shaped like him and filled it instead with the gun metal sky outside her window and the hum of her sewing machine. New creatures sprang forth â a saucy lavender cockroach, a ten-foot tall praying mantis worn on stilts, fat velvet bumblebees, and just because, one pale pink rose she wore as a kind of voluptuous hat, her freckled nose peeking out from between the petals.

Mornings, she woke early, did yoga stretches beside her bed, then fixed a pot of tea (plain old Lipton) and sat at her worktable, contemplating whatever bug-in-progress waited there. Eventually, she would punch the button on her answering machine and listen to the confident mothers who intended to book her for very special parties celebrating their most extraordinary children. These calls Ladybug returned promptly, with a practiced brightness reserved for all things bug-show related.

Rarely, there would be another message, from her sister in Akron, or her mother. Weeks later, she might phone back and leave an answer on their machines, thus avoiding much actual conversation, which worked for everyone. Theirs was not a close family, and time and distance had pushed them increasingly apart. Mostly, she was alone.

Tuesdays and Thursdays, Ladybug rode the subway to Manhattan to take ballet lessons in a dusty studio on 14th Street, followed by a meandering walk to the fabric stores in the 30âs. She knew all the grumbly old men who worked behind the counters there, and could lose herself for hours amid the satins and brocades, the buttons, sequins and beads. Her last stop would be a Korean market for a few groceries; just enough to fit in her backpack, then the long ride home, a forty-minute daydream.

Now Maxâs shoulder pressed against hers while the train swayed, picking up speed as it rattled across the bridge above the East River, reminding her that she wasnât alone and had slept with no one but her cat in over a year. Abruptly, she was aware of how much she wanted to. But then what? If she disappointed him, if he disappointed her, to run into each other at work would be agonizing, whereas now, it was always a happy surprise.

Ladybug stole a look at Max, who gazed out the window at the dejected towers of the housing projects ahead. Sheâd never been close enough to him to notice the scattering of gray hairs above his ear which didnât match his pink-cheeked-boy face. A face so much like those of the children he entertained that it was either scary, or perfect, or perfectly scary. He turned to her, catching the measurement in her eyes. She smiled a smile she hoped would say, donât worry, I like your contrasts. I like the way you sit there in charge of my crazy foam rubber, ferrying it like precious cargo clear to Brooklyn because itâs raining and we both hoped you might. I like it that youâre nice and I donât like it that youâre nice. Am I nice? I donât know. Max smiled back, at her, a little sadly, as if he could hear her babbling, uncertain heart.

The walk from the train to Ladybugâs loft smoothed things over some. Max had never visited Williamsburg and a close call involving a beat-up station wagon jammed with Hasidic Jews, their ringlets dangling, gave them plenty to talk about. Max, it turns out, was Jewish himself (non-practicing) and was curious about Ladybugâs religious roots (Lutheran, also non- practicing). Theology covered six blocks and three flights of stairs, but abandoned them once they stepped inside Ladybugâs loft. Alone at last, an anxious silence settled around them like a low-lying fog.

Max spotted Ladybugâs worktable and placed his load there, admiring an intricate set of wings which she explained were for her new housefly costume. She struggled through the fog to her kitchen area, trying to remember what you did when someone visited, since in the three whole years sheâd lived there, no one ever had. Then her Ohio upbringing came to the rescue and she began making tea, laying out honey, lemon slices, graham crackers, her grandmotherâs cups and saucers. Max sat at the kitchen table, petting her cat who lay curled in his lap, blissfully shedding.

There they were, then, sipping tea while rain pinged softly on the roof and the cat purred, when Max reached over and took Ladybugâs hand in his own. They sat just like that for a long time. It might have been days until they fell onto her bed, where days slid into weeks as they swirled and spun till somehow, night arrived and though they should have been hungry, they werenât. Finally, they slept. When Ladybug opened her eyes, it was really morning and the bed beside her was empty.

At first she though he might be in the shower, but the loft was silent and when she checked, there was no trace of Max. Not a damp towel, not a note. Only an indent on his pillow; the chalk outline of a good idea gone bad. Ladybug lay still, regret jagging through her. Then came tears, the worst betrayal of all, for Ladybug was not a crier. Pulling the blankets around her, she rolled onto her side, searching for comfort in the reliable gray sky outside her window, but the gray was gone and floating there instead was a rainbow bouquet of balloon birds, balloon butterflies, and one magnificent red balloon rose. She rushed to the window and looked down.

Three stories below, Max leaned against the building, patiently clutching his gift as it bounced and drifted on the morning breeze. As he had done at regular intervals for the entire two hours heâd waited there, Max looked up towards her window, but this time, he saw Ladybug. Beaming up at her, he waved both hands, in his excitement forgetting the balloons, which saw their chance and sailed up and out, across the rooftops, headed for the lonesome streets of Manhattan, where another heart surely needed winning.

You might also like:

The post Romance Short Story: âLadybugâ by Gail Bartley appeared first on Art of Conversation.

A Florida of Sun, Sky, Sea and Mind

One of the themes of âSunshine State,â Sarah Gerardâs striking book of essays, is how Florida can unmoor you and make you reach for shoddy, off-the-shelf solutions to your psychic unease.

Continue reading the main story

Gerard grew up in Clearwater, a beach city near Tampa. She writes about how her otherwise incredulous parents (they met in a biker bar; he was wearing a baby-blue Jimmy Buffett T-shirt) fell into New Thought, a mind-healing movement.

Almost as bad, they signed on with Amway. That company, co-founded by the father-in-law of Betsy DeVos, the secretary of education, can, many have argued, resemble a pyramid scheme.

Gerard decides that dabbling with Amway was, in her perfect phrase, a form of âachievement tourism.â She writes, âWe left reality for a moment and believed the impossible was possible.â

Photo

Credit

Alessandra Montalto/The New York Times

Continue reading the main story

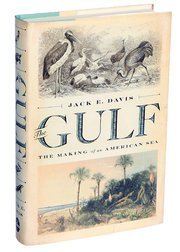

Gerardâs essay collection is one of two new books that examine the Florida experiment. The other is Jack E. Davisâs âGulf: The Making of an American Sea,â a sensitive and sturdy work of environmental history.

Obviously, the Gulf of Mexico does not belong solely to Florida. It is the 10th-largest body of water in the world. It touches several other countries â indeed, it is named for one of them â as well as other American states.

Continue reading the main story

But Davis lives in Florida, and that stateâs wet western edges run along a vast amount of the Gulfâ, like salt on the rim of a cocktail. He canât help but dwell often upon his home place.

Thanks to books by John Jeremiah Sullivan (âPulpheadâ) and Leslie Jamison (âThe Empathy Examsâ) and a handful of other young writers, the essay collection has new impetus and drama in American letters. The essay has gained ground on the short story.

Continue reading the main story

âSunshine Stateâ deserves to be talked about in this company, even if its essays are hit-and-miss. When Gerard is on, she is really on. Sheâs the author of one previous book, the novel âBinary Starâ (2015).

The first essay is a knockout, a lurid red heart wrapped in barbed wire. Itâs called âBFF,â and itâs about the authorâs intense friendship with a girl who grew up to become a stripper and who spent time in shelters for battered women.

Continue reading the main story

This essay is about attraction and betrayal, and has the sinister propulsion of a Mary Gaitskill short story. âYou shinier,â Gerard writes about her friend. âYou prettier. You taller. You thinner, more popular. In middle school, you had friends and I had you.â

Continue reading the main story

Theyâd had tattoos on their hips that read, when they stood side by side, âForever / & ever.â Their eventual split was devastating. The author had the means to get out of town; the friend did not.

Photo

Credit

Alessandra Montalto/The New York Times

Gerard catalogs the lies her friend told her, then she lists her own. She writes about her damage, splitting her face open while jumping from a train. This essay draws blood.

Continue reading the main story

Many of the essays in âSunshine Stateâ fall somewhere between memoir and journalism. Two of the longer pieces, about work to care for the homeless in Florida and about a troubled bird sanctuary, are serious and impeccably reported. But the authorâs voice is lost in the telling. Sheâs best when her evocations of the frenzy that is Florida are personal.

Historians, inspired by Fernand Braudelâs epic 1949 two-volume study of the Mediterranean Sea (1949), have written books about most of the worldâs important bodies of water. Davisâs âGulfâ is the first comprehensive history of the Gulf of Mexico, a place that tends to be, he persuasively argues, âexcluded from the central narrative of the American experience.â

Texas and Louisiana also have a great deal of Gulf-front real estate, and Davisâs book does not skimp on their histories. But since Gerard, Davis and I each grew up staring at the same blue-green water off Florida, I will stick with Florida in this review.

Davis carefully relates its history, from the stateâs native people and its earliest European explorers, through the early history of the United States and the arrival of tourists, developers and those who would fish and hunt Florida to depletion.

Continue reading the main story

The author has a well-stocked mind, and frequently views the history of the Gulf through the prism of artists and writers including Winslow Homer, Wallace Stevens, Ernest Hemingway and John D. MacDonald.

Continue reading the main story

His prose is supple and clear. About the arrival of motorized shrimp boats on the Gulf, he writes: âThey pushed farther out into the Gulf, the classical music of a wind-driven sea passage drowned forever by the heavy metal of internal combustion and snorting exhaust. Fishers discovered that if they worked past sunset, their trawls were filling with a new kind of shrimp, browns, which rose near the surface at night.â

Davisâs book functions, as well, as a cri de coeur about the Gulfâs environmental ruin. His book runs up through the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. That event aside, he writes, âEvery day in the Gulf is an environmental disaster, originating from sources near and far, that eclipses the spill.â

Continue reading the main story

âGoodbye North, Hello South,â Bessie Smith sang in âFlorida Bound Blues.â âItâs so cold up here that the words freeze in your mouth.â The words in Gerardâs and Davisâs books are sun-warm and, in their way, optimistic. Both writers make the effort, essential to any form of love, to see their state plain.

Continue reading the main story

The post A Florida of Sun, Sky, Sea and Mind appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Lit Hub Daily: March 28, 2017

The Best of the Literary Internet, Every Day

TODAY: In 1914, Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal is born.

Julio Cortázar on the hazy borders of memoir and fiction, and the fantastic violence of Latin American politics. | Literary Hub

How to write a libretto about a massacre: Harriet Scott Chessman tells the story of My Lai. | Literary Hub

Bookstore as political act: Scott Esposito finds resistance on the shelves. | Literary Hub

Julia Dahl: writing crime fiction among the pious. | Literary Hub

After facing complaints from parents and state lawmakers, a North Carolina school district has pulled Jacobâs New Dress, a book about a young boy who elects to wear a dress to school one day, from its first grade curriculum. | Cosmopolitan

âI do think there is something about this hybrid form that meets a need that is specifically female, one that is specifically marginalized by our culture.â An interview with Melissa Febos. | Bookforum

Fully entering into a different language involves a total upending of the self: Three translators weigh on what Arrival gets right (and wrong) about language learning. | Words Without Borders

âI read to be filled with a sense of wonder.â An interview with Kanishk Tharoor. | Los Angeles Review of Books

In honor of Buffy the Vampire Slayerâs 20th anniversary this month, a New York Times-curated list of Buffy fanfiction, by authors who range from 17 to 56. | The New York Times

âConsidering what climate change portends for our future, the subject ought to be the principal preoccupation of fiction writers the world over.â Amitav Ghosh on writing in the Anthropocene. | The American Scholar

His insurgent D.I.Y. purity is on full display: On a new volume of Bill Knottâs collected poems, which he may not have âbeen pleased to see . . . in print.â | The New Yorker

Gore Vidal on sex, Capote, and the pope in Tennessee Williamsâ memoirs. | Book Marks

The post Lit Hub Daily: March 28, 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

At PEN Awards, A Scaled-Up Atmosphere and Political Bent

PEN America hosted its annual literary awards at the New School in Manhattan on March 27 in a ceremony the organization hoped would be "celebration of literature on par with awards shows for other art forms," and which saw its biggest honors of the year bestowed.

While PEN announces the bulk of its winners, including the inaugural PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers, in advance of the ceremony each year, it saves its major awards for the ceremony itself. This year, the top award—the inaugural PEN/Jean Stein Book Award for the author of the year's "best book-length work"—went to Hisham Matar for Fathers, Sons and the Lands In Between. The PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay went to Angela Morales for The Girls In My Town. The PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize, which honors a first novel or collection of short stories, went to Rion Amilcar Scott for Insurrections. The inaugural PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement In International Literature went to Syrian poet Adonis for his full body of work.

The ceremony, hosted by former Daily Show correspondent and Halal in the Family creator Aasif Mandvi, was themed for the first time in PEN history, labeled Books Across Borders to "showcase the power of literature to transcend geographical, cultural, gender, and artistic boundaries, and to illuminate the impacts and influence of artists around the world on American thought," the organization said. The event was held on the heels of two widely-protested executive orders issued by President Donald Trump intending to secure American borders by halting the country's intake of refugees from a selection of predominantly Muslim countries.

Mandvi, a Muslim, began the evening joking about the danger of books crossing borders, noting that they could be "really bad libros," and suggesting that, should the president wish to keep Muslims from accessing the country, he might do so by building a wall "out of bacon. As a Muslim," he continued, "I know that would keep me out."

The ceremony featured a scaled-up atmosphere replete with musical performances and a dramatic reading of the work of Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright, screenwriter, and novelist Suzan-Lori Park by actors from the Huntington Theatre Company's staging of Park's play Topdog/Underdog under the direction of actor, singer, and director Billy Porter. Hamilton Leithauser, lead singer of indie-rock group the Walkmen, performed Leonard Cohen's song "Democracy" set to artwork by the artist David Mack and musician and composer Olga Nunes, and PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award winner Natalie Scenters-Zapico performed a poem about the U.S.-Mexico border along with accompaniment by violinist Ernesto Villalobos.

The event rounded up other star power as well, including ESPN's Jeremy Schaap, of SportsCenterT, and Tony Kornheiser, host of sports program Pardon the Interruption, the latter of whom regaled the crowd with stories of working with author William Nack at Newsday in the 1970s before presenting him with the PEN/ESPN Lifetime Achievement Award for Sportswriting. Tarell Alvin McCraney, the author of play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue and Academy Award–winning co-author of the script of its film adaptation, Moonlight, was also on hand to accept the PEN/Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater Award for a Playwright in Mid-Career.

"I have to admit this was a surprise," McCraney said as he accepted his award, nodding to the well-publicized flubbing of the conferring of the Academy Award for Best Picture: "And you'd think I'd be used to surprises by now."

Throughout the ceremony, PEN screened pre-filmed segments featuring each of the five nominees for the night's top award, the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award, reading from or discussing their shortlisted works. The segments, introduced by Mandvi, were similar to the highlight reels more customary at cinematic awards ceremonies such as the Academy Awards or the Golden Globes.

In closing, PEN America executive director Suzanne Nossel reminded the audience that "in our present political moment, words have new meaning." She added: "When words are used to harm, we use words to heal. When words are use to lie, we use words shed a light on truth. When words are stopped at the border, we use words to cross boundaries."

The post At PEN Awards, A Scaled-Up Atmosphere and Political Bent appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Horror Short Story: “Oakland Mothers, Oakland Wives” by Corey Quinlan Taylor

“Oakland Mothers, Oakland Wives” by Corey Quinlan Taylor is the First Place-winning story in the horror category of the 12th Annual Writer’s Digest Popular Fiction Awards. For complete coverage of this year’s awards, including an exclusive interview with the Grand Prize winner and a complete list of winners, check out the May/June 2017 issue of Writer’s Digest. And click here for more information about entering the 13th Annual Popular Fiction Awards.

In this bonus online exclusive, you can read Taylor’s winning entry.

Oakland Mothers, Oakland Wives by Corey Quinlan Taylor

I gave birth to my husband Morgan in 1863, five months after he died during the Battle of Gettysburg. The babe I held emerged as a vessel of my husband’s soul. He had told me this would occur, in the last letter he wrote, before getting shot in the leg during Pickett’s Charge. The .58 caliber bullet didn’t kill him; the infection and fever did.

Days after his delivery, my husband had no inclination to cry as most babies would. His smiles gave me solace. Though incapable of speech, his eyes expressed volumes to me. His hands, so soft and pink, could not hold a quill pen. I just assumed what his needs were. I would sit in the parlor of our home in Doylestown, with him on my lap and allowed him to see the letters and newspapers as I read them. Seeking his counsel in the form of yes and no questions, with a nod or shake of his head to guide me.

A learned man, fluent in German and Latin, he had no need for schooling during his years as a boy. He had no patience for children, though he was just as small. I grew accustomed to him recalling our courtship, or his expressions of consternation when gentlemen from our local church attempted to court me. I still held my youth and my husband had made sound financial investments. Like Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey, I kept the suitors at bay. Mr. Oakland was the only husband I ever had.

When he became capable of full speech, he pleaded that I keep his resurrection a secret. I asked if this ever occurred before.

“Yes. Many times.”

I asked if he always returned as a boy.

“I’ve had a woman’s form during several lifetimes. And if you’re wondering, I have dabbled in miscegenation. I didn’t live long as a mulatto – at least one of me didn’t.”

I asked if he ever had siblings.

“Yes, they were all me. We were one, minds in unison; experiencing multiple settings, multiple events, multiple encounters. Though we could never be more than three siblings of one mother or the connection would drift, become diluted. It’s madness: seeing a fourth son or daughter, and him or her completely shut down, isolated, unconnected, mentally gone. A freak. We took care of it.”

I asked my husband to explain.

“We took care of it; I will say no more.”

With the years passing, he became a man. He kept our love strong. We were discreet.

“I must take a bride, to live in a new form,” he said. “I cannot sire a child through you, my love. It’s forbidden.”

I understood; duty dictated that I’d give aid to his renewal. I invited local girls from established families for tea. Some were sweet enough, but not very savvy. I needed a young lady capable of protecting my husband when he became an infant again. There’s much horror during those months and years, of having an adult’s mind, though incapable of speech, incapable of walking, even feeding oneself. Like being buried alive in a beautiful coffin.

In 1886, my husband married a young lady named Beatrice – three years his senior, though that could not be helped. She was committed, intelligent, and dutiful. However, I decided to not tell her about my husband. Such things can never be explained between Oakland wives, they can only be experienced.

My experience? I love my husband. He died, then returned. I grew old. Now I sit on my deathbed: blind, weak. He and Beatrice visit from time to time. I still miss his face.

***

1927: Beatrice Oakland

We were never like those other people. The reserved people. The timid people. The morally obsessed people. It became pathology, really. The way husbands and wives declared before the world how righteous and cautious and unassuming they were, while hissing under fans and powdered cheeks about the shortcomings of others. I’m not sure who were worse, the wives of the pastors or the wives of the town councilmen. Authority has a way of tainting one’s spirit.

Mr. Oakland and I would attend picnics, recitals, and summer socials. From my periphery I could see eager lips whispering: how we held hands, or how he kissed me in tender ways unacceptable for most. My appearance often provoked their ire. Others wore their hair up with clasps and pins; I wore mine short. Others chose corsets and restrictive dresses in July; I wore blouses and pants. While most wives discussed cooking, sewing, and children, I joined my husband and the other men on the topics of politics, science, and commerce.

I fancied myself an amateur ornithologist, and I would regale summer social husbands with my mourning dove calls. I could also perform a raven’s cry, or that of a northern cardinal. The applause I received made Mr. Oakland smile. Even when the mayor’s wife, Agnes Johns, took it upon herself to ask my husband if he approved of such behavior, my beloved replied, “sunbeams don’t need approval to shine.”

The only time Mr. Oakland became insistent was on the matter of children. I understood when his mother invited me over for tea; it was with the possibility of becoming a bride for her son. I always found it odd that when he showed me affection she held an expression of resignation and duty, instead of joy. I chalked it up to a mother’s love, at first. Years later, I finally understood. I sobbed before Elizabeth, as she lay on her deathbed. She truly loved her husband, even when bound in the body of her son.

Years before that, he fascinated me. As he courted me, I grew to appreciate him … as a friend. My heart could not produce more. But in the most unusual way, I think he understood. And he began, almost intuitively, to treat me as an equal. To love me with a woman’s heart, and not a man’s assertion. With that, I accepted his proposal and we became as one. I even gave birth to his son and daughter. Twins.

The acts of an Oakland can rarely be explained without being witnessed. He wanted his son and daughter named after him, as he took on his departed father’s name: Morgan Oakland. After the first few days of their births, my son and daughter rarely cried. They spent their moments observing: the room, visitors, my actions, and hanging on every word spoken in their presence.

Mr. Oakland would ask about a neighbor who visited during his departure on a business trip. He would inquire about treatment for a bruise our daughter experienced after stumbling to the ground, or a cold our son caught from a local boy’s cough. When our children began speaking with his cadence, his mannerisms, I felt a streak of panic: my family sees the world through each other’s eyes. My five-year-old daughter had to rest my fears and inform me of her true self.

“I’m Morgan; we all are, Beatrice.”

I attended church, during my youth. In my realization of my husband and children, I recalled the biblical verse of Mark: the fifth chapter and the ninth verse, “And Jesus asked him, ‘What is your name?’ He replied, ‘My name is Legion for we are many.’”

In this case, I was not in the company of a New Testament demon. My family wasn’t – isn’t evil. They’re different forms, ages, and genders, all of the same spirit or personality.

My little girl pled to me, tearful, not to tell anyone. She trembled in my arms.

Why would I? It was 1896; people hadn’t been burned at the stake for hundreds of years, but I understood all the same. Sanitariums were just as horrific as the fires of inquisitors. And having one Oakland bound and hospitalized for insanity would become a prison for the other two – or how many more there are in the world.

So I acquiesced and raised our children – my husband.

On occasion, I needed a respite from the ambiguity of identity and familial roles. I knew a teacher, just outside of town, named Joan: a wonderful friend and a patient listener. I told her everything except our family’s secret, which still lifted such a weight from my heart.

Oaklands, being as they are, found out about my visits. Mr. Oakland insisted on having Joan join us for Sunday dinners, which soon included Friday dinners, and Saturdays as well. He never asked about my time with Joan. He never asked me to define my relationship with Joan. Perhaps it was his way of permitting my true self and maybe thanking me for never pushing back on having children, getting married to him, being courted. His mother – his wife before – was intuitive enough to know my heart. That didn’t matter, as long as I was strong willed.

Mr. Oakland died while reading the evening newspaper in 1918. An article about the Great War worked him into a rage. He was 55; our doctor said he had a heart attack. Our children experienced that sensation of death as well, through the emotional trauma. It took weeks to console my daughter, but my son Morgan was a 27-year-old lieutenant, stationed in Europe. Beyond my comfort and assurance.

Mr. Oakland left a stipend to hire Joan as an assistant in our Doylestown mansion. At least that was the official justification. Even in death, he understood me. And I continued to raise Morgan the best I could, despite her brother’s slaughter in a muddied trench in France. We are still a family, smashed and reassembled. We are whole.

***

1943: Isabelle Oakland

Some listen to American jazz for entertainment. The Résistance listens for messages about the Nazi officers, fuel deliveries, downed Allied pilots, and where to lay explosives for SS patrols. Each artist represents a scenario, each song a call for action. Louis Armstrong, George Gershwin, Lester Young, Benny Goodman, Jelly Roll Morton, Billie Holiday, and others, are like a spectrum of activities. Magnifying a mood, telling a story.

What better vehicle to convey our message to French brothers and sisters in arms. The idea and the albums belong to my son, Morgan Yves Oakland.

Spies and collaborators are never able to break our code … if one could call it that. Nor are they able to identify which radio station, at least among the pirated stations, is sending the information.

At first, I believed he had his father’s spirit – figuratively. For it’s rare to see creativity and toughness live harmoniously within a soldier, especially one from The Great War. I remember first meeting his father at a piano bar in 1918, so skinny in his brown uniform. His charisma filled in spaces his muscles could not. Yet, I fell in love and we shared much in our brief year and a half.

These memories had provided me peace when I gave birth to our son, not long after his father was killed in action. And then fear and disgust festered within me when I understood the truth. A truth I could not even confess to our village priest. Ironically, it was the Nazis that brought us together, again. In our darkest times, I could not deny my son.

Though we were poor, his other self – an American cousin of great kindness wired us funds, which we used to buy weapons. She even mailed us albums, to find some respite.

One night, while hiding from the Vichy police, Morgan had the idea about how Rhapsody in Blue, could be a musical piece to signal an attack. At first our friends considered it impossible, but someone in the upper echelons of the Maquis thought it was a superb idea. We just needed radio equipment, and two trucks to broadcast.

“Can you telegram your … cousin-self to send us the funds, Morgan?” I had asked.

My beloved’s soul spoke through my son, “No need, ma petite, she sees our conversation through my eyes. I am Oakland.”

Our strategy gained us many triumphs: officers killed, soldiers rescued, and more importantly information sent to the British and Americans. I was so proud of my boy, though I knew with the look he gave me; this was not his first war. Wisdom and innocence cannot inhabit the same heart.

One evening while broadcasting Strange Fruit, sung by Billie Holiday, a patrol had found one of our trucks – Morgan manned the vehicle. The scuffle and arrest could be heard over the radio. The brutes didn’t even have the courtesy to permit such a beautiful song to finish.

My son knew what would happen if he were arrested. He chose to detonate the potato masher on one of the soldiers’ belts. I lost my husband twice, but I lacked the moral courage to tell him I loved him, because of old taboos preached by old men.

And now I play the songs my boy once played. He, in the form of his female American cousin, sends fewer letters, but still wires cash through the Red Cross or missionary groups beyond the suspicions of the Vichy and the Nazis.

France will find liberty once again, and if possible, I would like to visit and embrace this cousin. Just to reunite once more with the son and husband I lost. I, too, bore a strange fruit.

***

1986: Morgan Kate Oakland

My mother was born a twin in 1891; she gave birth to me in 1921, though out of wedlock. Illegitimate acts occur for legitimate reasons. In my case, for survival and to prevent our … my family fortune from falling into the hands of some suitor unsuited for the burden of responsibilities that come in sharing my history, my state of mind, or the synecdoche nature of what it means to be an Oakland.

Oh, I’ve been a woman before – multiple times. But in different centuries, consequences occurred from taking on some sympathetic husband with good intentions, or a spouse compelled to dominate my thinking, my opinions, and my sensibilities. Each time, whether for the best or not, we – I – we lost control.

Having more than three children, with the fourth or fifth completely lost to my pan-cerebral thought and being. Numb to us. Abominations. They would have been empty vessels, devoid of senses. Devoid of a mind – completely. With their brainstems providing barely enough motivation to wail for food and drag across the floor like a crippled pup.

I can tolerate much, but not disconnected Oaklands. I took no joy in correcting those errors. Yes, I lied each time. If a baby didn’t catch consumption, she or he would be exposed to plague, or smallpox, or perhaps they turned the wrong way in their crib and could not breath. Afterwards, I would claim that my womb could bear no more. Few men truly understand a woman’s biology, so they would acquiesce.

That is, until those cold nights; those nights of heavy drink and boredom. When a man attempts to treat a wife like someone less than the person he committed vows to during the wedding ceremony. I’ve been a warrior and a soldier in enough men’s bodies across the centuries to easily subdue a drunkard husband while I reside in a woman’s body. The first time results in a bruise and a warning. The second time, I explain to a village constable how my departed husband fell and struck his skull on a stone stair. I will not be subjugated in any form. I am Oakland.

After America’s war with the Axis Powers, I felt it best to follow my departed mother’s path and bring children into this world. I had a cousin and aunt in France, resistance fighters, but they were both eventually killed. I also have a Negro extended cousin, from an Oakland branch going back more than a century ago. But in the mid-20th century, his autonomy was limited; significantly more than this brunette white woman in Pennsylvania. In my mind and heart, I live his life to this day, as he simultaneously lives mine. I know what I speak of, completely.

So I needed a male heir – a vessel. I asked a loyal friend, Melvin, to drive me to a summer resort in the Adirondacks. We purchased a room, and spent the week watching married couples, or families with smart, strong sons. Young men of good breeding.

I would spend my time reading by the lakes in my bathing suit, or taking sailing tutorials in dinghies with tall bright sails. Several men approached me on the sly, beyond the eyes of their wives or attentive mothers. We’d talk news, politics, and literature: some were exceptionally dull, while others were arrogant. I noticed a somber man, nursing his bourbon on the rocks, for an hour or so each afternoon. He noticed me noticing him, yet remained. I approached. His name was George.

He was a professor before the war, and afterward, he felt his nerves exposed. A draining sensation, which alienated him from his wife and daughter. I understood. We talked for hours.