Roy Miller's Blog, page 231

March 30, 2017

A Trove on the Women’s Suffrage Struggle, Found in an Old Box

It would be 46 more years before the 19th Amendment guaranteed women the right to vote. The letter, saved by Hooker, ended up stashed in a wooden box along with nearly a hundred others relating to the suffrage struggle. And there they sat for more than a century, unknown to historians or seemingly anyone else.

Continue reading the main story

Now, the letters have been acquired by the University of Rochester as part of a larger trove of material that some are calling the biggest discovery of its kind in decades.

“It’s a stunning collection,” said Ann D. Gordon, a retired professor at Rutgers University and the editor of the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers Project. “That it’s being delivered all in one piece, with such a clear provenance, is remarkable.”

The collection, which Ms. Gordon is so far the only outside scholar to see, includes 26 letters from Anthony, 10 from Stanton and dozens from other suffragists. There are also broadsides, pamphlets, newspaper clippings and other material that Hooker kept in a kind of circulating library, many with “I.B. Hooker, please return” marked in her handwriting.

Photo

A letter from Susan B. Anthony to Isabella Beecher Hooker from 1874.

Credit

J. Adam Fenster/University of Rochester

Continue reading the main story

The material, mainly dating from 1869 to 1880, may not upend current scholarship, but Ms. Gordon said it sheds light on a contentious period within the suffrage movement, while underscoring the degree to which the movement was driven by complex networks of on-the-ground activists.

“We don’t pay enough attention to what a local movement this was,” Ms. Gordon said. “We’ve warped the story by only knowing the names of the national leaders.”

Continue reading the main story

Isabella Beecher Hooker, the youngest daughter of the prominent minister Lyman Beecher, had lived with her husband and three children for a time in Nook Farm, a literary colony in Hartford, whose residents included her half sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Mark Twain.

The collection came to light last year, when Elizabeth and George Merrow of Bloomfield, Conn., were cleaning out a jumble of books and papers, including some that had been retrieved from the former Hooker home, which Mr. Merrow’s grandfather, heir to a major sewing machine manufacturer, bought in 1895.

Continue reading the main story

Bob Seymour, a local book dealer, had recognized the signature of Elizabeth Cady Stanton on one letter. He sent the box to a colleague, Adrienne Horowitz Kitts, who didn’t initially have high hopes.

Continue reading the main story

“We figured we’d get some stuff about the family, maybe some New England manufacturing history,” she said, referring to the Merrows.

But as she started sorting through the material, dusting away ample mouse droppings, she was stunned to realize it was a rich archive of suffrage material.

Continue reading the main story

“It really shows you what these women went through,” Ms. Kitts said. “They really busted their butts for us.”

Lori Birrell, the special collections librarian for historical manuscripts at the University of Rochester library, said she was moved by a letter from 1872 in which Hooker describes her feelings of inadequacy in an early political speech.

Photo

Pages from a petition for women’s suffrage to Congress, 1876-1878.

Pages from a petition for women’s suffrage to Congress, 1876-1878.Credit

J. Adam Fenster/University of Rochester

Continue reading the main story

“Sitting here in 2017, that really blew me away,” Ms. Birrell said. (The library, a leading repository of early suffrage material, did not disclose the price it paid for the collection.)

But Ms. Gordon said the collection was very much “a political archive,” illuminating the years immediately following 1869, when the suffrage movement had split over the 15th Amendment.

A New York faction, led by Anthony and Stanton, opposed the amendment on the grounds that it would enfranchise black men but leave out women of all races. A Boston-based faction, led by Lucy Stone and others, strongly supported it, arguing that including women would doom the amendment and that women’s suffrage would be better pursued at the state and local level.

“I believe that just so far as we withhold or deny a human right to any human being, we establish a basis for the denial and withholding of our own rights,” Stone wrote to Hooker on Aug. 4, 1869, in a letter in the new collection explaining her support for helping black men win the vote first.

Continue reading the main story

There was a fight about which side would get Hooker, who was “considered an important catch,” Ms. Gordon said.

Continue reading the main story

Ultimately, Hooker went with the Anthony-Stanton wing. But she still worked to unify the movement. In 1871, she organized a national suffrage convention in Washington, which pushed the argument that women, under the recently adopted 14th Amendment, were citizens and therefore already had the right to vote.

Continue reading the main story

The letters, Ms. Gordon said, also depict Hooker’s tireless work on the ground in Connecticut — one of at least 22 states where women attempted to vote between 1868 and 1873.

Hooker died in 1907, 13 years before the 19th Amendment went into effect. She was important, Ms. Gordon said, not just as an activist but also as an archivist.

“She was someone who was part of the conversation and decision-making, and also someone who kept everything,” she said. “That’s huge.”

Correction: March 31, 2017

A capsule summary on Thursday about the women’s suffrage movement referred incorrectly to when women received the right to vote. A number of states allowed women to vote well before the final passage of the 19th Amendment, in 1920; it is not the case that women were not granted the right to vote until that year.

Continue reading the main story

The post A Trove on the Women’s Suffrage Struggle, Found in an Old Box appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Russia blamed for Amazon listing of anti-Trump book | Books

Publishers believe that Russian individuals are behind the creation of an fake book parodying a self-styled manual for resisting US president Donald Trump and other populist leaders, with the author, historian Timothy Snyder, claiming the listing to be the latest attack in a series of efforts by Russians to undermine his work.

A non-existent colouring book by “Timothy Strauss” appeared as a listing on Amazon.co.uk with the same title as Snyder’s On Tyranny. The blurb for Strauss’s book said it contained “lessons to Make World Great Again” [sic] – a slogan used on pro-Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin posters that have appeared across the Russian Federation.

Snyder, a Yale professor who specialises in European history and the Holocaust, said: “The idea of making the world great again appears, to my knowledge, only in Russian on pro-Trump posters in the Russian Federation.” He added: “The attack basically confirms several of the lessons in On Tyranny, such as [No] 14, on the importance of digital privacy.”

Snyder’s book is a distillation of insights he has gleaned from 20th-century history about how tyrants can be resisted and presents practical actions to take against repressive regimes. This week, his UK publisher Vintage marked the launch of the book with a poster installation in a London street featuring the entire book. It is believed to be the first time a book has been promoted in such a way.

A No 1 bestseller on Amazon, the professor said he thought the listing was inspired by publicity for the book, which has proved popular on both sides of the Atlantic – coupled with a bad week for Trump, whose attempts to quash Obamacare were defeated in Congress.

“Russia has shown a tendency to jump in to help him at such times,” he said. Pointing to the fight for the White House last October, when Russian diplomacy criticised opposition to Trump’s pro-torture position, he added: “Perhaps someone who supports Mr Trump construed my book’s No 1 ranking on Amazon as a small part of his bad week.”

Snyder claimed there had been a pattern of Russian action to undermine another of his previous – Bloodlands – which tackled Hitler and Stalin. “The Russian foreign ministry, in an annual list, claimed that the existence of Bloodlands somehow constituted a human rights violation – odd for a book … whose subject was the violation of human rights,” he said.

A Russian company also bought the rights to publish the book Bloodlands in Russian, Snyder said, but the translation never appeared.

Once alerted to the fake book listing, Vintage informed Amazon, which removed it immediately. An Amazon spokesman told the Guardian: “All authors must follow our guidelines and those who don’t will be subject to action including potential removal of their account. The book in question is no longer available.”

The post Russia blamed for Amazon listing of anti-Trump book | Books appeared first on Art of Conversation.

We Are All Detectives Now: When Literary Plots Get Mysterious

There’s something reassuring about reading a story in which a heroic detective saves the day. Maybe it’s through tracking down a killer; maybe it’s finding a missing person. There’s that sense of closure, that sense that the protagonist has done the right thing and restored some sort of order. But what happens when the world feels askew—when those kinds of stories don’t entirely line up with the world around us, with questions of heroism, with ideas of power and authority.

Subverting detective-story tropes isn’t a new thing. Joe Meno’s The Boy Detective Failed and Jedediah Barry’s The Manual of Detection took archetypal characters and narratives in strange and surreal directions. Michael Chabon’s The Final Solution juxtaposes an aging Sherlock Holmes’s efforts to solve one final mystery with the much greater historical crime that he remains unaware of. Derek Raymond’s The Factory novels focused on an unnamed investigator whose psyche slowly unravels as a result of the horrors he witnesses through his job; instead of the cathartic or triumphant moment of revelation, the conclusions of the later novels in this series promise future trauma and wrenching emotions. Raymond’s A State of Denmark took another facet of crime fiction in another direction: the protagonist here is a journalist living in exile after running afoul of his country’s dictatorial head of state. Here, though, the story isn’t about a crusading writer taking down a corrupt state; instead, it’s a bleaker look at the way that power can be abused.

As a writer with a fondness for messing with these tropes myself—one of the two leads in my book Reel is basically a pulp detective in a world without any pulp detectives, and is a mess as a result—I have a fondness for stories that find something new to say about detective fiction, or that uses its features, tropes, and story beats to say something new about human existence.

Patty Yumi Cottrell’s Sorry to Disrupt the Peace does a tremendous job doing exactly that. Helen Moran, the novel’s narrator, returns to her hometown after a long absence when news comes of her brother’s suicide. She decides to investigate his death, believing there’s something more that she’s not being told, and does so by applying the language of detective stories to her investigation. “I needed to put his life into an arrangement that made sense,” she states at one point. One chapter begins with a suitably hard-boiled opening.

Article continues after advertisement

October 2nd, the first real day of my investigation, it was pitch-black outside, darker than the darkest mornings in Manhattan when the garbage has not yet been collected and the rats are at work.

And throughout the novel, she does what she believes a detective should: asks question of people who knew her brother, hypothesizes, retraces his steps. But there’s a hazard there, too, and it’s one that she brings up in another context, when musing on the origins of a book in her childhood home. “I realized I had created an entirely fictional narrative in my mind about the book of cars and its origins,” she says—and there it is, the fine line between detection and speculation.

From the readers’ side, we’re given Helen’s personality to figure out, which is a mystery in and of itself. Both she and her brother were adopted, and she constantly prefaces the words “mother” and “father” with “adoptive”—so is her voice a result of feeling alienated, or are there other psychological issues at work? There are certain moments where her descriptions of events seem slightly off: her constant references to herself as “Sister Reliability,” a nod to her work with troubled children, for instance, and her memories of a falling-out she had with a local art scene of which she was once a member.

Cottrell’s novel has a thoroughly complex and compelling narrator, questions of memory and family, and a fantastic sense of place. What makes it especially memorable is how its awareness of the structure of a detective story enables it to go to some very bleak, very powerful emotional places. It’s a moving and unsettling novel with a fantastic narrative voice at its center—and if Helen Moran isn’t necessarily the great detective she believes herself to be, her perspective on life and the stories we tell isn’t an easy one to shake.

The narrator of Katie Kitamura’s A Separation is also an unlikely detective, but she’s far less willing to embrace the role. As the novel opens, she and her husband Christopher have been separated for several months, though few people are aware of this fact. Christopher’s mother contacts her: Christopher has gone missing. And so the narrator travels to a Greek island to begin a search for a man whose presence or absence summons feelings of ambivalence.

A Separation has plenty of mystery-esque elements: a missing person, a frayed marriage, an investigation. But its pensive pacing suggests something else—a prose equivalent of a film like Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger, where character and setting take center stage. There is, ultimately, a crime, but it doesn’t happen until halfway through the novel. When that happens, it doesn’t suddenly become a whodunnit; instead, the inclusion of violence—and the question of whether the crime really was a crime, rather than simply an accident—heighten the themes of deception and trust that have come before it.

“Once you begin to pick at the seams, all deaths are unresolved (against the finality of death itself, there are the waves of uncertainty in its wake),” the narrator muses late in the book. It’s significant that Kitamura also juxtaposes this disappearance and its aftermath with an event that characters in the novel follow on the news: a cruise ship that seems to have vanished into thin air. Is a crime a crime if there’s no explanation? At what point does someone disappearing enter the territory of the deceased, to be mourned? And who, ultimately, determines that? The languorous investigation in A Separation raises a host of questions with mysterious answers.

In the vanished cruise ship of A Separation, there are plenty of echoes of the 2014 disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370. Olivia Sudjic’s Sympathy references the flight directly; here, too, it stands in for the inexplicable, for a mystery that may well go wholly unexplained, but was no less lethal for it. Sudjic’s novel is decidedly contemporary: social media plays a significant role in it, and one of the supporting characters is a thoroughly unpleasant tech-bro type involved with an app that aids people in finding threesomes.

In Sympathy, searches and investigations abound, chief among them how protagonist Alice Hare goes in search of a writer named Mizuko Himura living in New York. Questions of online communications and online personas suffuse the novel; taken in combination with the investigatory riffs in the book, it pushes towards a larger point: we are, arguably, all detectives now. Social media can easily be used for surveillance, for one thing, and different personas used online to gather information also have their crime-fiction counterparts.

At one point, Alice muses about another character’s capacity for insights—which, again, hearkens back to questions of mysteries and investigations.

“It never ceased to amaze me how she just had the facts, always, in her head. It occurred to me that if, or when, she died, a whole load of facts, a body of knowledge, might disappear without a trace.”

In the end, Sympathy turns out to be—like so many mysteries—a book about the past rising back into the present and setting everything askew. It’s a haunting conclusion to a novel that’s frequently disarming.

The opening sentence of Richard Beard’s The Apostle Killer also suggests the aftermath of a crime: “First, find the body.” But the conceit of Beard’s novel soon reveals itself: its setting is a strange blend of the modern era and the early days of the Roman Empire, blending the familiar with, well, other things that may be familiar, but in different contexts, such as this scene where Gallio, the novel’s investigator protagonist, muses over his options.

…Gallio can harass him on suspicion of the murder of Judas. Gallio is ready to invoke Interpol, confiscate Jude’s papers, close his beloved hospital, make his life a misery, but sitting beside him on the stairs Gallio doesn’t believe that Jude is the murderer of Judas. Nor is he Jesus in disguise.

Herein is the trick of Beard’s book: we’re reading this from the perspective of a skeptic, someone whose job places him at odds with the earliest Christians, and who thus fundamentally doesn’t quite get the narrative that he’s in the middle of. Occasionally, this comes off as a little too clever—but there are also some deft reimaginings of familiar stories, such as the idea of Judas being paid thirty pieces of silver for his betrayal.

In the end, Beard’s novel resembles the decades-spanning works of the likes of James Ellroy and David Peace. For all that Gallio is both protagonist and butt of a cosmic joke, his struggles feel real, even as his logic becomes more contorted: “Jesus has promised to return in the lifetime of his beloved disciple, and John is the last disciple standing. Therefore he is the beloved.” It’s a strange and unsettling book, which takes a strange elevator pitch and turns it into a compelling tale of obsession.

Structure and perspective can count for a lot. Much like how Gallio in The Apostle Killer is arranged as that rare detective with less information than the reader, the way the connections between the trio of desperate characters in Cynan Jones’s Everything I Found on the Beach becomes apparent and transforms a gritty working-class setting into something much more harrowing.

The novel’s prologue opens with the police making their way around a crime scene and describing the unsettling sights that they discover—in other words, from the outset, the reader is clear that this probably won’t end happily. From there, Jones showcases three primary characters: Grzegorz, who’s left Poland in search of a better life; Hold, a fisherman struggling with recent trauma; and Stringer, who’s enmeshed in the world of organized crime. Each one seems to be carrying on with his life as best they can, but soon, circumstances force them out of their comfort zones, and things repeatedly take a turn for the worse.

Had Jones told this novel in a more linear fashion, it might have played out more like a traditional crime novel. Here, in this more fragmented approach, it feels like a series of small-scale tragedies that gradually accumulate into something much bleaker. Comparisons and contrasts between the three men emerge, and a sense of disorientation—echoing the ways in which these characters find themselves out of their depth—comes to dominate the proceedings.

There are a host of things that are compelling about detective fiction on its own. The permutations of it that appear in these five novels show off some of the ways in which its elements can be used in a new context to create a feeling of revelation or disorientation. What is the sum total of a mystery? What comes of removing some of those components, or placing them in an entirely new context? These books offer a host of answers.

The post We Are All Detectives Now: When Literary Plots Get Mysterious appeared first on Art of Conversation.

There’s a Vice Munchies Cookbook Coming This Fall

In 2009, David Chang, owner and chef of Momofuku, hit the streets of New York City to eat and drink with Vice Media. The ensuing video, which sees Chang plowing through fried chicken in Koreatown and preparing his famous pork buns for late night revelers, was the first in a series called Munchies, which documents what famous chefs eat and drink during boozy nights on the town. The videos were such a success that Vice eventually launched Munchies, a food website and media channel, in 2014. Now, Munchies is forging new ground with the announcement of a three-book print cookbook deal with Ten Speed Press, with senior editor Emily Timberlake editing.

The first book, Munchies: Late-Night Meals from the World's Best Chefs, by J.J. Goode, Munchies editor-in-chief Helen Hollyman, and the editors of Munchies, is due out in fall 2017. The book is based on the Munchies web series (since rechristened as Chef's Night Out), and features stories of chefs’ debauchery, as well as their go-to recipes to soak up alcohol.

When asked why Munchies, and Vice Media, which courts a digital, Millennial audience, decided to make the foray into print, Munchies publisher John Martin said the online content actually pushed them in the direction of a cookbook. “We discovered that people were spending a really large amount of time on each page in the recipe section on Munchies, which means people were actually cooking from our recipes,” said Martin. “We view books as a platform, and if it’s one that our audience is on, we’ll produce for it. It’s a natural and smart brand extension, and in the food world a book is a real sign of having arrived.”

With close to 150 videos in the Chef’s Night Out series, the source material was in place. The book will include recipes and tales from 65 top chefs, including Anthony Bourdain, Dominique Crenn, Chang, Danny Bowien, Wylie Dufresne, and Enrique Olvera. San Francisco chef Brandon Jew's fried fish sandwich is inspired by the McDonald's Filet-o-Fish, a meal that “reminded him of his grandparents and their times at Micky D's,” according to Hollyman. “Only this filet o' fish has a beer batter that fries up to an airy crunch, a crisp slaw, and a tangy seaweed spiked tartar sauce.” There's more involved dishes, like Dufresne's Gemelli Pasta with Peas, Chicken, and Mushrooms, or Tien Ho's Lemongrass and Thai Basil Pork Pie (a Vietnamese inspired meat pie).

The book will be promoted through all of the Munchies platforms, and will be teased through trailers on the site’s YouTube channel, which Martin estimates will have roughly 2 million subscribers come launch. “You’ll see a print ad in Vice magazine, and our staff, talent and friends will all be promoting on their socials too,” said Martin. “We’re pretty good like that as a company, when we have a major announcement, everyone pulls together to promote the hell out of it. There are some fun contests and launch events planned too. We do like to party.”

The post There’s a Vice Munchies Cookbook Coming This Fall appeared first on Art of Conversation.

‘Richard Nixon,’ Portrait of a Thin-Skinned, Media-Hating President

And members of Nixon’s own party feared for his stability. As vice president, he once flew into a rage after contending with a group of hostile student journalists at Cornell University. “What scares the hell out of me is that you would blow sky high over a thing as inconsequential as this,” an adviser told him. “What in goddamn would you do if you were president and get into a really bad situation?”

Photo

Credit

Alessandra Montalto/The New York Times

These similarities in character lead to eerily similar behavioral consequences. In 1968, Nixon opened up a back channel to the president of South Vietnam, assuring him he’d get further support if he could just hold out for a Nixon presidency and resist Lyndon B. Johnson’s offers to broker peace. Nearly 50 years later, Michael Flynn had private discussions with the Russians that seemed to promise them a friendlier American policy — if they could just sit tight until Trump was inaugurated.

Both men went on to claim that their predecessors had wiretapped these discussions. Nixon said he’d been tipped off by J. Edgar Hoover.

Continue reading the main story

Confirmation of Nixon’s meddling in Johnson’s peace efforts is the only real news that “Richard Nixon” breaks. But startling revelations are hardly the only criterion for a good Nixon biography. He’s an electrifying subject, a muttering Lear, of perennial interest to anyone with even an average curiosity about politics or psychology. The real test of a good Nixon biography, given how many there are, is far simpler: Is it elegantly written? And, even more important, can it tolerate paradoxes and complexity, the spikier stuff that distinguishes real-life sinners from comic-book villains?

The answer, in the case of “Richard Nixon,” is yes, on both counts. Farrell has a liquid style that slips easily down the gullet, and he understands all too well that Nixon was a vat of contradictions. Some readers may find Farrell’s portrait too sympathetic — he’s as apt to describe Nixon as a tortured depressive as he is to call him a malevolent sneak — but more readers, I think, will find this book complicating and well-rounded.

Continue reading the main story

It’s also hard to read a one-volume history of a president’s life without feeling like you’re crawling over the dense folds of an accordion. But most chapters in “Richard Nixon” have room to breathe.

The development of Nixon’s character in this book is subtle. He doesn’t start out as a rampaging narcissist and megalomaniac. Over time, it was power combined with profound insecurity that misshaped him. He had no ability to tolerate the slings and arrows of outrageous public humiliations, of which he probably suffered a disproportionate many, and he responded with the venom of a toadfish. The press trolled him. Even Dwight D. Eisenhower trolled him. Once, Ike was asked to name an important decision Nixon had helped him make as his vice president. “If you give me a week, I might think of one,” he replied.

Continue reading the main story

Farrell follows a mostly chronological structure. We go to Whittier, Calif., where Nixon was raised by an ogre of a father, a fellow so bad at farming he couldn’t grow lemons. As a young man, Nixon was awkward, square, hopeless at making small talk. I could read a whole book of his love letters to Pat, his future wife. They’re endearing and pathetic, the desperate pleas of the runt of the litter.

Photo

John A. Farrell

John A. FarrellCredit

Kathy Kupka

“Yes, I know I’m crazy!” he wrote in a note he shoved under her door. “And that … I don’t take hints, but you see, Miss Pat, I like you!”

Continue reading the main story

In some ways, the Watergate years, because they’re so familiar, are the least interesting stretch of this book. (Though here’s a detail I’d forgotten: Nixon had a mole in almost every opponent’s campaign, a thumb in every pie.) It’s Farrell’s chapters about race that prove the most textured and dizzying: It was over this issue that the president’s Quaker upbringing and Machiavellian impulses seemed most overtly at war. When Nixon first ran for Congress, he was made an honorary member of the local N.A.A.C.P., so progressive was he on matters of race. Yet while running for president, he made it clear he’d “lay off pro-Negro crap,” and once in office he mastered the rhetorical art of exploiting racial grievances. Thus began the South’s transformation from a block of Democratic-voting states to a G.O.P. sea.

You can also draw a through line from Nixon’s contempt for the liberal elite to Trump’s boastful claims of political incorrectness. That vaudevillian public disdain for East Coast intellectuals, Ivy League blue bloods, cosmopolites — all of it started with Nixon. It was he who first used the phrase “the silent majority.”

He came by that populism honestly. He started from nothing, and he found the culture of Washington, which went gaga over pretty, privileged boys like John F. Kennedy, infuriating. What his populism didn’t mean, however, was stripping the welfare state to the studs. The public still had a taste for big government back then. During Nixon’s presidency, he signed the Occupational Safety and Health Act and established the Environmental Protection Agency.

Continue reading the main story

The most charitable biographies paint Nixon as a tragic figure, and that’s precisely what the president is here. Farrell’s Nixon is smart and ambitious, a visionary in some ways (China), but also skinless, both driven and utterly undone by self-doubt.

It may be the way he differs most, at least psychologically, from our current president. Trump has shown almost no evidence of self-doubt, ever, about anything. He appears to sail through life unencumbered by introspection. He’d yield no more depth if you used an oil rig.

But grandiosity and profound insecurity often find the same form of public expression: recklessness. “I sometimes had the impression that he invited crisis and that he couldn’t stand normalcy,” Henry Kissinger once said. I’ll leave it up to the reader to determine which president he’s best describing.

Continue reading the main story

The post ‘Richard Nixon,’ Portrait of a Thin-Skinned, Media-Hating President appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Indies Recommend: Skylight Books | Literary Hub

As the nation’s only non-profit distributor, Small Press Distribution is dedicated to getting small press literature to the people who want to read it. As such, we’re grateful to our main customers—indie bookstores—the outward-facing purveyors who present our books to the public with flair and aplomb. To celebrate the great individuality of our favorite indie stores across the country, SPD’s asked a few of them to shine a monthly spotlight on their ten all-time favorite SPD-distributed titles. This month, we’re excited to host Los Angeles bookstore Skylight Books.

Skylight Books has been part of literary Los Angeles for the last twenty years. Our strengths lean towards literary fiction, regional history, current events, and the arts. We host a full schedule of author events, have a cat, a tree in the middle of the store, and, of course, skylights to let in the golden California light.

Amy Berkowitz, Tender Points

(Timeless, Infinite Light, 2015)

Article continues after advertisement

This exercise in self-awareness and collective awareness struck me hard. Tender Points is an offering—Amy lays down her real body experience, sheds a tear and a light on a life of pain, that many-layered thing. These essays give a deep sharp breath to a voice that we cannot ignore, deny, systematize, dismiss or suppress, even if their speaker can’t always get out of bed.

–Jenn Witte

[image error]

Sam Chanse, Lydia’s Funeral Video

(Kaya Press, 2015)

It’s a one-woman show, described as apocalyptic satire about abortion, shooting a funeral video, and comedy, all taking place within 28 days—a perfect menstrual cycle. A dark,funny, bold approach to all kinds of intersectionality.

–Kelsey Nolan

[image error]

Valerie Mejer, Rain of the Future

(Action Books, 2014)

My favorite poetry collections create worlds and logics unto themselves. Mejer’s book travels in worlds of grief, decomposition, and growth. Strange shades of light. A gauzy near-reality. Its presentation as an English-Spanish parallel text creates an exciting complementary lyricism.

[image error]

Chelsey Minnis,

Poemland

(Fence, 2009)

Books don’t make me laugh very often. This book makes me laugh. To feel some heavy things very acutely in that space, as well—that’s a special book I think.

[image error]

Frank Stanford, Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You

(Lost Roads Publishers, 2000)

The hungriest book I’ve read. I’m sometimes shocked that reading this wasn’t a dream.

–John Rossiter

[image error]

John Brian King, LAX: Photographs of Los Angeles 1980-84

(Spurl Editions, 2015)

Little has changed in the last thirty-five plus years: LAX remains an awful, awful airport to spend time at. In the early eighties John Brian King’s lens documented this hotbed of anxiety and frustration, providing a portrait of just how much it sucked to arrive in L.A. by air a generation ago, and contextualizing that, while it still sucks now, at least it’s traditional.

[image error]

Erin Wunker, Notes from a Feminist Killjoy: Essays on Everyday Life

(BookThug, 2016)

The longstanding worldwide tradition stifling the thoughts and voices of women is, at best, blasé. An education for all in feminist writing both present and past is essential to the social growth and development of our species. This book is one of many fantastic titles to propagate this effort.

–Clark Allen

[image error]

Ottessa Moshfegh, McGlue

(Fence Books, 2014)

McGlue comes-to, tied up on a boat and having possibly committed a crime he does not remember. The language rolls and pitches perfectly—I felt as messed up as the drunken sailor in this short novel.

[image error]

Dodie Bellamy, The TV Sutras

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2014)

All of Dodie’s books affect me, and this one gets inside my body like sunrise meditation or a delicious veggie sprouted rice bowl. These sutras, received from the glow of the television set, coupled with Bellamy’s honesty and rhythms, make my chemicals flood and flow.

[image error]

Anne Carson, Short Talks

(Brick Books, 2015)

I like Anne Carson’s poems. I really like how she plays not just with poetic form but even with structure of a “book” (see: Nox and Float). I saw her read at Temple in a cemetery and it was like going to a rock concert. This early collection speaks to me with its prose stylings and cultural references.

–Steven Salardino

The post Indies Recommend: Skylight Books | Literary Hub appeared first on Art of Conversation.

8 New Books We Recommend This Week

Devotees of Elena Ferrante should check out the latest piece in the puzzle of her identity: a novel by Domenico Starnone, “Ties,” that offers a response to her early work “Days of Abandonment.” Bonus: “Ties” is translated from the Italian by the Pulitzer Prize winner Jhumpa Lahiri, who also provides a captivating introduction. Two nonfiction books tackle the timely issue of inequality: one from the point of view of constitutional governance, the other from the perspective of your dental health. Philatelists and oenophiles, we’ve got you covered: “The One-Cent Magenta” tracks the travels of the most valuable stamp in the world, while “Cork Dork” chronicles the oft-hungover adventures of a would-be sommelier (and pairs nicely with something sweet).

Radhika Jones

Editorial Director, Books

CORK DORK: A Wine-Fueled Adventure Among the Obsessive Sommeliers, Big Bottle Hunters, and Rogue Scientists Who Taught Me to Live for Taste, by Bianca Bosker. (Penguin Books. $17.) Bosker was an editor at The Huffington Post when she became obsessed with the world of sommeliers and decided to change her life. For 18 months, she shadowed renowned wine fanatics, hoping to understand their obsession and to become a certified sommelier herself. Her book is the result of her immersion in that world. Our critic Jennifer Senior wrote: “Bosker’s journey into this sodden universe is thrilling, and she tells her story with gonzo élan.”

THE CRISIS OF THE MIDDLE-CLASS CONSTITUTION: Why Economic Inequality Threatens Our Republic, by Ganesh Sitaraman. (Knopf, $28.) Inequality is one of the defining challenges of our time, but beyond unfairness, what is its ultimate threat? Sitaraman argues in his fine book — both a history and a call to arms — that the Constitution is premised on the existence of a thriving middle class, and that the current explosion of inequality will destroy it.

TEETH: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America, by Mary Otto. (New Press, $26.95.) If the idea of death from tooth decay is shocking, it might be because we so rarely talk about the condition of our teeth as a serious health issue — or a serious class issue. This health journalist’s history of dentistry illuminates the class line between those who spend thousands of dollars to perfect their smiles and others who suffer from, and even die of, preventable tooth decay.

QUICKSAND, by Malin Persson Giolito. Translated by Rachel Willson-Broyles. (Other Press, $25.95.) A Swedish teenager on trial for her involvement in a mass shooting instigated by her boyfriend is the focus of this courtroom procedural, the first of the author’s four novels to be translated into English. As the facts of the case are revealed, so are the economic and racial tensions underlying the contemporary Swedish setting.

THIS LONG PURSUIT: Reflections of a Romantic Biographer, by Richard Holmes. (Pantheon, $30.) Holmes is well known as the biographer of Shelley, Coleridge and others. “He does for biography what Cheryl Strayed did for the Pacific Crest Trail,” Stacy Schiff writes in our review. The third of his books about the art of writing other people’s lives examines some familiar and other lesser-known figures as well as his own ecstatic practice.

Continue reading the main story

THE ONE-CENT MAGENTA: Inside the Quest to Own the Most Valuable Stamp in the World, by James Barron. (Algonquin, $23.95.) A scrap of reddish paper with faded lettering and clipped corners starts out in 1856 with a face value of a penny. A century and a half later, it’s worth $9.5 million. A Times reporter’s account of this unique 19th-century stamp is a window into the romance — and obsession — of stamp-collecting.

TIES, by Domenico Starnone. Translated by Jhumpa Lahiri. (Europa, paper, $16.) The husband of the woman who has been identified as Elena Ferrante offers an emotionally powerful novel about a fraying marriage that is a sort of sequel to Ferrante’s “Days of Abandonment.” Lahiri provides a fluid translation and a brilliant introduction explaining her own preoccupation with the book.

ILL WILL, by Dan Chaon. (Ballantine, $28.) Chaon’s dark, disturbing literary thriller encompasses drug addiction, accusations of satanic abuse and a self-deluding Midwestern psychologist. Chaon dismantles his timeline like a film editor, building the narrative with short, urgent chapters told from different perspectives.

Continue reading the main story

The post 8 New Books We Recommend This Week appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Juan Pablo Villalobos Volunteers the Nation of Mexico to Build Trump’s Wall

Let’s build the wall. And okay, we’ll pay for it, us Mexicans. But we’ll build it ourselves, and we’ll put an aid station every twenty kilometers, a proper shelter with doctors, food, water, beds where people can rest and gather their strength, and English classes. And most importantly, we’ll have lots of doors all up and down the wall, thousands of them. Doors that can only be opened from one side: ours.

Let’s build the wall. And okay, we’ll pay for it, us Mexicans. But first we’re going to ask for a construction loan from the government of the United States. Or the World Bank. Or, even better, the IMF. There will be a bidding process for the project of designing the wall. Another one for building it. And another for managing it once it’s ready. We’ll solicit bids only from our friends, of course. And the winning bids will come from our very closest friends. Those who design the wall will go way past deadline—way, way past deadline—years past deadline. (As architects they’re mediocre at best, but they’re our closest friends.) So the construction process will begin years late. And then there will be problems with the permits. And problems with the suppliers. And labor strikes. Two months after the first section is built, damp spots and cracks will appear, so construction will be suspended temporarily. The years will come and go, and with a little luck, so will presidents of the United States, until one who isn’t interested in having a wall comes along. Better still: one who asks that its construction be halted. (Obviously we won’t be paying back the loan.)

Let’s build the wall. And okay, we’ll pay for it, us Mexicans. Let’s build a green wall, an ecological wall—a hedge. More specifically, a hedge made of marijuana plants. We will of course first legalize marijuana as a construction material. And we’ll watch as the immigration patterns change: people from the north now flocking south to smoke our wall. Against all expectations, we won’t detain them. On the contrary. We’ll all meet up at the wall, and a new era of friendship and brotherhood will spring up between our two countries.

Let’s build the wall. And okay, we’ll pay for it, us Mexicans. But let’s build it as a tourist attraction, an amusement park. We’ll call it “The Wall of Shame,” or something like that. Right next to it we’ll build museums focusing on racism, imperialism, discrimination. And there will be viewing platforms so that we can watch what’s happening on the other side from a safe distance. Tourists will come from all over the world—Japan, China, Germany, Sweden. Our wall will make us a fortune and create thousands of jobs. Jobs that will be filled, of course, by immigrants who can’t make it across.

Let’s build the wall. And okay, we’ll pay for it, us Mexicans. An invisible wall, like the emperor’s invisible clothes. A wall that only smart people can see. We Mexicans will build it with invisible bricks, and invisible steel too. Freed from material limitations, we’ll be able to build it really, really high—a thousand meters high. And really thick: two kilometers thick. On the day we inaugurate it, we will say to the president of the United States, “Here’s your wall. It’s very high, and very thick, but only smart people can see it.” I’m sure the president will be thrilled.

Translated by Roy Kesey.

The post Juan Pablo Villalobos Volunteers the Nation of Mexico to Build Trump’s Wall appeared first on Art of Conversation.

March 29, 2017

How to Craft the Perfect Antihero

I’ve always been drawn to the darker side of fiction, to stories that brood on the imperfections of the human soul and the obstacles that war, poverty, social upheaval, illness, or just plain bad luck, throw in our way. All day long, I try to be exceedingly bright and pleasant to my neighbors and colleagues, my family, my dog. But when I pick up a novel, or begin to write one, I want to indulge in the shadows. Fortunately, modern literature is crowded with “antiheroes” – protagonists who lie, cheat, cower, abuse, and kill. The classic example is Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Crime and Punishment: a sick, seedy, resentful, deranged student who brutally murderers a poor old woman and her daughter, simply in order to test his misguided theory of moral exceptionalism. Some readers might find him repulsive, but he remains one of the most fascinating and affecting characters in all of fiction. Indeed, the novel was the literary hit of 1866, and total sales are still climbing.

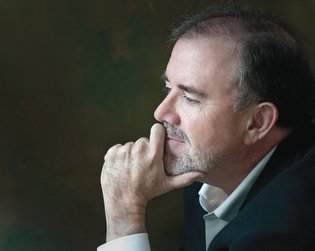

This guest post is by David Weisberg. Weisberg is an English professor, author of several books, and playwright, and his new novel The American Plan (Habitus Books/April 2017) has been described as a cross between Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and Ian Fleming’s James Bond. His protagonist, Philip Narby, is modeled after literature’s classic anti-heroes – characters with few redeeming qualities that continue to fascinate readers.

This guest post is by David Weisberg. Weisberg is an English professor, author of several books, and playwright, and his new novel The American Plan (Habitus Books/April 2017) has been described as a cross between Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and Ian Fleming’s James Bond. His protagonist, Philip Narby, is modeled after literature’s classic anti-heroes – characters with few redeeming qualities that continue to fascinate readers.

In my novel The American Plan I created my own brand of antihero. All along, I knew I ran the risk of alienating potential readers. My protagonist, Philip Narby — an unapologetic drug addict, a frequenter of prostitutes, cynical and paranoid, eager to betray friend and country alike to advance his own ends — has few redeeming qualities. Yet his story is compelling, and he carries the plot and themes forward with energy and excitement. Without giving away too much of the book, I can explain some of the choices I made in crafting Narby as a credible, effective, even sympathetic protagonist, despite the gaping flaws in his character.

1. Narrative Perspective

After much consideration, I decided to write the entire novel from Narby’s perspective, using a tightly controlled “over-the-shoulder” third-person voice. This accomplished two things: first, the more the reader sees the world through the eyes of the protagonist, the more likely she is to sympathize with his plight, despite his failings. Second, by avoiding the first-person, I created separation and tension between the protagonist and the world against which he struggles. Even though the reader sees the world more or less through Narby’s eyes, it’s not his world, not his voice. A first-person voice would have revealed perhaps too much about Narby’s inner life. So, while the reader understands Narby’s intimate desires and fears, at the same time he remains a mystery.

This was difficult to pull off. I had a model for this type of suspenseful narration in Patricia Highsmith’s masterful The Talented Mr. Ripley. Indeed, Tom Ripley is one of the most fascinating antiheros of American fiction.

[Want to Write Better? Here Are 10 Habits of Highly Effective Writers]

2. Motivation

Only villains are evil — antiheros are deluded, damaged individuals.

My protagonist’s flaws are drawn from the psychology of everyday life, only intensified: the need to be loved, the craving to find relief from pain and anxiety, the fear of being abandoning, the resentment that arises from seeing people who are no better than you thrive, while you languish.

In particular, I used two of the most complex of human emotions — resentment and humiliation — to motivate my protagonist. These composite emotions weave together arrogance, fear, pride, insecurity, envy, and jealousy into a knot of potential conflict and action. They also activate the protagonist’s vulnerability, his longing to be accepted by the very society he hates. They make him more human, yet no less craven or self-serving.

Again, I had as one of my models Highsmith’s Tom Ripley. Ripley’s resentments and humiliations, centered around his low social class and his repressed sexuality, fill him with longing and compel him to murder the one person he admires and then — in a twist the still fills me with wonder — assume the identity of the man he kills.

3. Secondary Characters

Like most antiheroes, my protagonist is an alienated loner, on the run, with enemies who, whether real or merely products of his paranoia, reflect the inherent injustice of the world he inhabits. I had to be very careful here, because I did not want to excuse my protagonist’s bad behavior, or worse, make him into a victim. But clearly, he is surrounded by others who, because they are socially powerful, cause harm and suffering through their hypocrisy and arrogance.

To serve this end, I created a few secondary characters who are blatantly afflicted with irrational hatreds and violent prejudice. So, though my antihero also carries these taints to a degree, his struggles against those worse than he ameliorate his own failings, giving the dark cloud of his character a tenuous silver lining, so to speak.

[The 5 Biggest Fiction Writing Mistakes (& How to Fix Them)]

4. An Open Ending

To be true to my antihero protagonist, I could not have him “win” at the end of the novel. Having survived a series of struggles, physical and emotional, he is still alone, lost, unrepentant and unredeemed, yet nevertheless somehow changed. To show this change, I contrived a final, explosive scene that brought together the very worst and the most positive aspects of his nature, as though he were purging himself of all that had gone before, and leaving the possibility, no means assured, that he might still find a way to redeem himself or find a measure of happiness. He stands on the threshold of something new.

If these fiction-writing strategies intrigue you, I invite you to pick up The American Plan and judge how effectively I created a hero who carries the day, even though you might not want to invite him to dinner. Or maybe you would.

ORDER NOW:

ORDER NOW:

The Brainstorm New Ideas Value Pack is designed to

help you succeed with proven tips on structures, hooks,

characters, dialogue, viewpoints, settings, and more.

Only available online here at the WritersDigestShop.

Thanks for visiting The Writer’s Dig blog. For more great writing advice, click here.

Brian A. Klems is the editor of this blog, online editor of Writer’s Digest and author of the popular gift book Oh Boy, You’re Having a Girl: A Dad’s Survival Guide to Raising Daughters.

Follow Brian on Twitter: @BrianKlems

Sign up for Brian’s free Writer’s Digest eNewsletter: WD Newsletter

Listen to Brian on: The Writer’s Market Podcast

You might also like:

The post How to Craft the Perfect Antihero appeared first on Art of Conversation.

William McPherson, Book Critic and Novelist, Dies at 84

Under his editorship, Book World took its place as one of the leading literary publications in the United States, and his wide-ranging, elegantly written reviews played no small part in establishing its reputation. In 1977, awarding him the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism, the prize judges noted his “broad literary and historic perspective.”

Continue reading the main story

In late middle age, Mr. McPherson unexpectedly delivered a novel, “Testing the Current,” a coming-of-age tale about an 8-year-old boy living in a small Midwestern town in the late 1930s. More than five years in the writing, it was published in 1984 to the kind of critical superlatives to which Mr. McPherson, as an editor, might have applied the blue pencil.

The novelist Russell Banks, writing in The New York Times Book Review, called it “an extraordinarily intelligent, powerful and, I believe, permanent contribution to the literature of family, childhood and memory.” He added, “From the first sentence of ‘Testing the Current’ to the last, there is not one false note, one forced image. It is a novel written with great skill, and with love. It’s what most good first novels merely aspire to be.”

After writing a sequel, “To the Sargasso Sea,” published in 1987, Mr. McPherson embarked on a new journalistic adventure. On something like a whim, he headed to Romania after the fall of its dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu, and stayed for nearly seven years, filing reports for Granta, The Wilson Quarterly and other publications.

Continue reading the main story

He pulled a last rabbit from his hat after he had returned to Washington and settled into a quiet life of occasional journalism, declining health and dwindling finances. In 2014 he chronicled his predicament, precisely and eloquently, in The Hedgehog Review.

His essay, “Falling,” described the downward spiral of a genteel man of letters who, through a combination of bad luck, bad investments and unrealistic expectations, now knew what it felt like to sit on a bench with a quarter in his pocket and no bank account.

Continue reading the main story

The essay struck a nerve with readers and attracted widespread critical attention. What made it so “somber and revelatory,” James Wolcott wrote in his Vanity Fair culture blog, “is that the author is giving us the park bench perspective of what it means to be old and poor now, with no hope of reversing the downward trajectory.”

Photo

The cover of the novel “Testing the Current.”

Credit

Simon and Schuster

“And,” he continued, “more importantly, what it feels like. And what it feels like is a daily scalding of shame, humiliation and being disregarded as a nobody.”

Continue reading the main story

William Alexander McPherson was born on March 16, 1933, in Sault Sainte Marie, Mich., where his father, Harold, was the manager of the Union Carbide plant. His mother, the former Ruth Brubaker, was a homemaker.

Continue reading the main story

He attended public schools and enrolled in the University of Michigan in 1951. After four years of study with no degree in sight, he was encouraged by school officials to try his luck elsewhere. He spent two years at Michigan State University, without earning a degree, and served a short stint as a merchant seaman before deciding, after a short visit, that Washington seemed like a nice place to live.

In 1958 he found work as a copy boy at The Post, which quickly made him a staff writer for the women’s page. In 1963 he was appointed travel editor. He later took a last, desultory stab at higher education, studying at George Washington University for two years, again leaving without a degree. He left The Post to become a senior editor at William Morrow in 1966.

Continue reading the main story

In 1958 he married Elizabeth Mosher. The marriage ended in divorce. In addition to his daughter, Mr. McPherson is survived by two grandchildren.

In a 1987 interview with Publishers Weekly, Mr. McPherson said that he had no intention of writing a novel, or, as he put it, to “add another tree to the pulp mill.” But while he was walking to work one day in 1977, he said, a mental picture appeared unbidden: A woman on a golf course on a summer morning, taking a practice swing.

Continue reading the main story

“The scene hit me with such force that I sat down on the curb,” Mr. McPherson told Washington Independent Review of Books in 2013. “It was so vivid; I saw it with such clarity and intensity that I couldn’t get it out of my head. At home in my office that night I decided I should describe what I had seen.”

In a rush, he produced 12 single-spaced pages. And over the next five and a half years, the novel took shape, with the first paragraph intact.

It began: “That summer morning, in the distance, Daisy Meyer bent her blond head over her club, a short iron for the short sixth hole, in effortless concentration on her practice swing. Still engrossed in her projected shot, and seemingly oblivious to the murmurings of the women on the porch, she walked over to the ball, addressed it, and crisply shot it off.”

The novel, told through the intensely observant eyes of its young hero, Tommy MacAllister, blended crystalline description with the confused musings of a preadolescent mind struggling to make sense of events. In 2013, it was reissued, to much fanfare, by New York Review Books Classics.

Continue reading the main story

In “To the Sargasso Sea,” Tommy made a return appearance, this time as a 40-year-old playwright navigating a series of midlife crises. Mr. McPherson planned a third installment but never completed it.

One of the rare negative reviews of “Testing the Current” — perhaps the only one — appeared in Book World, of all places, written by the Canadian novelist Robertson Davies.

Continue reading the main story

“Actually I don’t think he’d read the book,” Mr. McPherson told The Chicago Tribune in 2013. “He said it was a novel about a kid who loves golf, and that’s not quite what it’s about.”

Continue reading the main story

The post William McPherson, Book Critic and Novelist, Dies at 84 appeared first on Art of Conversation.