Roy Miller's Blog, page 228

April 3, 2017

Photo Mania: MoCCA Arts Festival 2017

This content was originally published by on 3 April 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

This year's MoCCA Arts Festival, an annual gathering of independent and self-published comics and graphic novels, attracted a record crowd. PW was there to capture images of the weekend comics festival.

Source link

The post Photo Mania: MoCCA Arts Festival 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

2017 April PAD Challenge: Day 3

This content was originally published by Robert Lee Brewer on 3 April 2017 | 4:55 am.

Source link

I’ve found over the years that most people who can make it through three days have the stamina to keep poeming for 30. So let’s get through this together!

For today’s prompt, take the phrase “(blank) of Love,” replace the blank with a word or phrase, make the new phrase the title of your poem, and then, write your poem. Possible titles could include: “Water Bottle of Love,” “Smart Phone of Love,” “Toothbrush of Love,” “Tweet of Love,” or any number of blanks of love. I actually kind of love this prompt and am surprised I’ve never done it before.

*****

Learn how to write sestina, shadorma, haiku, monotetra, golden shovel, and more with The Writer’s Digest Guide to Poetic Forms, by Robert Lee Brewer.

This e-book covers more than 40 poetic forms and shares examples to illustrate how each form works. Discover a new universe of poetic possibilities and apply it to your poetry today!

*****

Here’s my attempt at a Blank of Love Poem:

“antiperspirant of love”

she warns me against setting

words of love down at her feet

because words can be revised

she’s more interested in things

that make a real impact like

the dinner & movie of love

or the spending time alone

of love or her all-time favorite

the antiperspirant of love

because she likes boys who

know how to work up a sweat

& still manage to smell sweet

*****

Robert Lee Brewer is Senior Content Editor of the Writer’s Digest Writing Community and author of Solving the World’s Problems (Press 53). He believes in the power of love (that strong, sudden, and sometimes cruel force of nature described by Huey Lewis & the News).

Follow him on Twitter @RobertLeeBrewer.

*****

Find more poetic posts here:

37 Common Poetry Terms.

Cywydd Llosgyrnach: Poetic Form.

Jaswinder Bolina: Poet Interview.

The post 2017 April PAD Challenge: Day 3 appeared first on WritersDigest.com.

The post 2017 April PAD Challenge: Day 3 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Now Batting: 14 New Baseball Books

This content was originally published by DANIEL M. GOLD on 2 April 2017 | 8:55 pm.

Source link

Photo

Credit

Patricia Wall/The New York Times

It happens every spring. It’s time to play ball, so publishers fill out a new lineup card of biographies, team histories and other baseball scholarship. This season must begin by acknowledging the surreality that after 108 years, the Chicago Cubs are again World Series champions. “The Plan” (Triumph, $24.95), by David Kaplan, is a chronicle of the project to turn “one of the worst organizations in baseball” into “a dynasty in the making.” Kaplan starts with the 2009 purchase of the franchise by Tom Ricketts, and the subsequent wooing of Theo Epstein, the general manager behind two titles for the formerly cursed Boston Red Sox. Chicago’s farm system is stocked and Joe Maddon, the Tampa Bay Rays manager, is signed ahead of the 2015 season. Add youngsters like Kris Bryant and Kyle Schwarber, and free agents like Jon Lester, and a long-losing club is finally No. 1. There’s too much front-office esoterica — one appendix lists clauses from rooftop-seating contracts for buildings around Wrigley Field — but Cubs fans won’t mind.

As for New York teams, “Casey Stengel” (Doubleday, $27.95), by Marty Appel, is the ultimate biography: Stengel not only played for the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants, he managed the Dodgers before steering the New York Yankees to their greatest run of dominance and became the first manager of the New York Mets. Paul Dickson’s “Leo Durocher” (Bloomsbury, $28) chronicles the adventures of Leo the Lip, the colorful player (briefly for the Yankees, later the Dodgers) and manager (for the Dodgers, Giants and other clubs) who stayed in the sports pages for more than 40 years.

Steve Steinberg’s “Urban Shocker” (University of Nebraska, $32.95) recalls a Yankees pitcher who should be better known for his name alone. A spitballer who was traded to the St. Louis Browns, Shocker had four 20-win seasons before returning to New York in time to be part of the 1927 championship team. “Piazza” (Sports Publishing, $24.99), by Greg W. Prince, revels in a more recent and beloved player. The best-hitting catcher of all time, Mike Piazza was already a Los Angeles Dodgers star when he was traded twice in 1998, first to the Florida Marlins, then to the Mets. After all Piazza did for the team (and the team for him), Prince’s book explains why it meant so much to New York fans that Piazza went into the Hall of Fame last year as a Met.

Around the league, former players telling stories include Rick Ankiel, the St. Louis Cardinal who lost his ability to pitch. In “The Phenomenon” (PublicAffairs, $27), written with Tim Brown, Ankiel speaks of succumbing to the anxiety disorder commonly called the yips, then reclaiming his career as an outfielder. Ankiel has company. Dennis Snelling’s compelling biography, “Lefty O’Doul” (University of Nebraska, $27.95), tells of the pitcher who, after a sore arm, became one of baseball’s greatest hitters and hitting coaches before helping to establish the game in Japan. “Ballplayer” (Dutton, $27) is a confessional memoir from Chipper Jones (with Carroll Rogers Walton), the likely Hall of Famer who spent his entire 19-year career with the Atlanta Braves. Mets fans know he enjoyed beating their team so much that he named one son Shea, after Shea Stadium; they may not recall that Jones hit his first major-league homer there. He details that moment and many others, including off-field behavior that led to two divorces.

Continue reading the main story

“One Nation Under Baseball,” by John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro (University of Nebraska, $29.95), looks at how the turmoil of the 1960s sowed the seeds for today’s game. A recurrent theme is ballplayers’ fight for higher wages, and when the labor lawyer Marvin Miller was hired in 1966 to lead the players’ union, it was all over but the court filing: The Curt Flood case taking on baseball’s reserve clause would eventually lead to free agency. This excellent read also covers race relations and other social issues, as well as the decade’s most memorable teams, players and events.

Free agency would eventually disrupt all clubs, but its earliest victims may have been the Oakland A’s. “Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $26), by Jason Turbow, recounts the team’s early-1970s dominance, when it won three straight World Series with a lineup that included Reggie Jackson, Joe Rudi and Sal Bando and a pitching staff anchored by Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue and Rollie Fingers. By 1976, free agency broke up the squad, and the club’s owner, a sympathetically drawn Charlie Finley, would sell it a few years later.

“Off Speed” (Pantheon, $23.95), by Terry McDermott, tracks the evolution of pitching from its earliest days, when the ball was thrown underhanded, to the modern science of hurling one at virtually superhuman speeds. McDermott describes nine pitches, weaving player and coach interviews into an absorbing examination of this arcane art. (Along the way he discloses secrets of the game: How have I never heard of Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud?) As Jane Leavy did in “Sandy Koufax,” McDermott frames his book around the nine innings of a perfect game; here it’s the one Felix Hernandez of the Seattle Mariners threw in 2012. An ideal counterpart is “Almost Perfect” (Lyons, $26.95), by Joe Cox. As that baseball fanatic Tolstoy almost wrote, “All perfect games resemble one another; each imperfect game is imperfect in its own way.” Cox analyzes the 16 games between 1908 and 2015 in which pitchers retired at least the first 26 batters they faced, only to see perfection elude them.

Continue reading the main story

The post Now Batting: 14 New Baseball Books appeared first on Art of Conversation.

April 2, 2017

Boom Times for the New Dystopians

This content was originally published by ALEXANDRA ALTER on 31 March 2017 | 2:09 am.

Source link

“American War” is one of several new dystopian novels that seem to channel the country’s current anxieties, with cataclysmic story lines about global warming, economic inequality, political polarization and the end of democracy. If there’s a thematic thread connecting this crop of doomsday books, it could be crudely summarized as, “Things may seem bad, but they might become much, much worse.”

Photo

Credit

Alessandra Montalto/The New York Times

In Lidia Yuknavitch’s novel “The Book of Joan,” the planet in 2049 has been destroyed by war and climate change, and the wealthy have retreated skyward to a ramshackle suborbital complex controlled by a celebrity-billionaire-turned-dictator who continues to suck resources from Earth. “I built a world that is only a small distance from our present tense,” Ms. Yuknavitch said in an email. “One in which our current aims have simply played out to their logical conclusions: endless war, environmental degradation, the exploitation of Earth as a resource, the brutal stratification of humanity.”

Similar catastrophic events propel Zachary Mason’s “Void Star,” a mind-bending novel in which rising seas have rendered large swaths of the planet uninhabitable, and impoverished masses huddle in favelas in San Francisco and Los Angeles, while the rich have private armies and armored self-driving cars and undergo life-extending medical treatments. Mr. Mason, a computer scientist who specializes in artificial intelligence, envisioned a world where the boundaries between machines and people have grown increasingly porous, and a powerful, godlike A.I. hacks into people’s minds.

Continue reading the main story

The future is even bleaker in Michael Tolkin’s “NK3,” which takes place in Los Angeles, after a weaponized microbe developed by North Korean scientists has swept the globe, destroying people’s memories and identities. The writer Chris Kraus called the novel “brilliant and barely speculative” and labeled it “the first book of the Trump era.”

Continue reading the main story

(For readers longing for a sliver of utopia, slightly less alarming visions of the future can be found in Kim Stanley Robinson’s “New York 2140,” in which the city is partly submerged by rising oceans but remains vibrant; and Cory Doctorow’s darkly funny “Walkaway,” a forthcoming novel about an idealistic man’s search for purpose in a country that has been leveled by extreme weather, economic disparity and the collapse of civil society.)

Dystopian and postapocalyptic fiction has been a staple on the best-seller lists for years. Young-adult series like “The Hunger Games” and “Divergent” have sold tens of millions of copies and spawned blockbuster film franchises, and prominent literary writers like Cormac McCarthy and David Mitchell have experimented with end-of-the-world scenarios in their novels. But the current obsession with the collapse of civilization seems less like a diverting cultural trend and more like a collective panic attack.

Continue reading the main story

As pundits and historians fret about the erosion of American democracy and the creep of totalitarianism, readers are flocking to dystopian classics like Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” and Sinclair Lewis’s “It Can’t Happen Here.” Not long after Donald J. Trump’s inauguration, sales for George Orwell’s “1984” surged, spurred by controversy over Kellyanne Conway’s use of the Orwellian phrase “alternative facts.”

“People are finding comfort in dystopian books, or maybe more accurately, they’re finding answers in them,” said Matt Keliher, the manager of Subtext Books in St. Paul, who said “1984” and “The Handmaid’s Tale” are among the store’s top-selling titles.

Mr. Keliher has become a fervent evangelist for “American War,” which he predicts will be one of the spring’s most widely discussed novels. Critics have heaped praise on Mr. El Akkad’s debut; in The New York Times, Michiko Kakutani called “American War” “a disturbing parable” and compared it to works by Philip Roth and Mr. McCarthy.

Continue reading the main story

“When you’re reading it, it’s pretty difficult not to project yourself 70 years into the future and imagine that this has happened,” Mr. Keliher said.

Mr. El Akkad — who is soft-spoken and self-deprecating, and repeatedly apologized during an interview for talking too much — said he was wary of being lauded as a prophet.

Continue reading the main story

“I would love to say I envisioned what would happen, but I never intended to write a timely book,” he said.

Continue reading the main story

Born in Cairo and raised in Qatar, Mr. El Akkad, 35, moved to Canada as a teenager and studied computer science at Queen’s University. After graduating, he became a reporter for The Globe and Mail, where he covered a foiled terrorist plot in Toronto, the war in Afghanistan and the popular uprisings in Egypt.

Continue reading the main story

When he started writing the novel three years ago, Mr. El Akkad wanted to bring the horrors of sectarian warfare home for American readers, and to show that the desire for revenge is universal. To research “American War,” he traveled to Louisiana, Georgia and Florida, and read about the Civil War. He also drew heavily on his experience as a war correspondent. A passage about a volunteer distributing polio vaccinations in a refugee camp was based on an encounter he witnessed in Afghanistan, while a gruesome torture sequence came from his research on the American military’s treatment of prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and the Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. “I don’t think there’s much in this book that hasn’t happened; it just happened far away,” he said.

“American War” takes place in the southern United States toward the end of the 21st century, after a civil war has broken out over fossil fuel use. The novel’s protagonist, a girl named Sarat, has fled with her family to a refugee camp near the Tennessee border. There, she is recruited and radicalized by a rebel leader with ties to a Middle Eastern empire that has emerged as a global superpower as the United States collapses into chaos.

Though the premise seemed obviously speculative when Mr. El Akkad first dreamed up the plot — what if a foreign power meddled in American politics, driving a deeper wedge into partisan fissures? — it feels almost too close now.

Mr. El Akkad wonders if readers will be drawn in by the novel’s inadvertent timeliness, or repelled by its unsettling proximity to reality.

“I can totally see fatigue setting in,” Mr. El Akkad said. “This is a disturbing image of a future that might be nearer than we think.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Boom Times for the New Dystopians appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Andrew McCarthy’s Newest Role: Young Adult Novelist

This content was originally published by MARIA RUSSO on 31 March 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

“I was always the confidante, never the boyfriend,” he said. “When I was 15, I looked very young. I would stand in front of the mirror wishing I could know what I would look like in 10 years.”

His mother nudged him to audition for the school play, and he was cast as the Artful Dodger in “Oliver.”

“I finally felt like, ‘There I am,’” he said.

He no longer minds so much that people still identify him with the work he did in the ’80s. “When I go, it will be ‘Andrew “Pretty in Pink” McCarthy dies’ — which is fine!” he said. “I ran from all that for years.”

Photo

Mr. McCarthy on his legacy: “When I go, it will be ‘Andrew “Pretty in Pink” McCarthy dies’ — which is fine! I ran from all that for years.”

Credit

Jessica Lehrman for The New York Times

Readers of his best-selling travel memoir, “The Longest Way Home,” know that by his 30s he had stopped drinking and rediscovered that feeling of “there I am” by going it alone to far-flung places. He kept a notebook and spent a year trying to persuade a travel magazine editor to give him a shot. He has since published dozens of travel essays and has won awards, including the 2010 Travel Journalist of the Year from the Society of American Travel Writers.

Continue reading the main story

Before dedicating himself to his young adult book, Mr. McCarthy spent seven years working on a novel “about a married guy who had a one-night fling and had a child and spent 25 years keeping it a secret.” It was terrible, he said. Then, one day, while waiting for a plane to take off, he started writing from the point of view of his favorite character, the 15-year-old daughter.

Continue reading the main story

“I was just messing around,” he said. “I would do anything to avoid writing the other book.” The pages came easily, and he realized “the big novel was like a dead tree in the woods and this was a nurse tree that sucked up all the roots.”

Continue reading the main story

His protagonist, Lucy Willows, lives in an unnamed New Jersey town based on Westfield, where Mr. McCarthy’s family lived until he was 15, when they moved to Bernardsville. Furious at her father after learning about her secret half brother, Lucy jumps on a train to New York City and ends up on a solo journey to Maine.

Mr. McCarthy said he had not read any of the recent, similarly realistic young adult novels by the likes of John Green and Rainbow Rowell, who have become publishing juggernauts. But he has embraced the idea of writing for a teenage audience. “I thought, if there’s truth in this, it would be a book for that extraordinary teenage moment in life, because everything is so important, it’s life and death, and you’re the only one who’s ever gone through it,” he said.

Continue reading the main story

He tested a draft on a teenage neighbor, who told him Lucy’s voice sounded legitimate.

A waiter approached with a soda refill, prompting Mr. McCarthy to sweep a copy of “Just Fly Away” out of view. “They’d start asking about it,” he said apologetically. “I’ve come here for years and years.” He lived nearby briefly, but these days he lives in the West Village with his wife and three children, one from his first marriage. “I’m very happy down there,” he said. “I’m basically walking the same streets I walked in college” — he spent a few years at New York University before leaving to act full time — “but it’s different every day, and now I’m doing it with kids and a dog.”

After lunch, we headed to Teavana, where he ordered a takeout darjeeling. “My wife is Irish,” he said. “I now drink tea all day.” While we sat on a bench in Central Park, at times saying nothing, I recalled his description of a teenage character in “Just Fly Away”: “a loner who likes to mingle.” It’s the vibe Mr. McCarthy gives off.

Continue reading the main story

In addition to writing and directing for television, Mr. McCarthy has also become a somewhat reluctant stage dad. His daughter, Willow, played Matilda in the Broadway production of “Matilda the Musical,” which closed on Jan. 1.

“We went to see ‘Matilda,’ and she was like, I want to be in ‘Matilda,’” Mr. McCarthy said. “At that point she had been the frog in the school play; she was not an actor. I was like, O.K., sweetheart. So the babysitter was looking online for all things ‘Matilda,’ and there was an open call and Willow was like, ‘Can I go?’”

Continue reading the main story

Five auditions later, she won the part that she played for eight months.

“She was wondrous and wonderful, and she loved it,” Mr. McCarthy said. “I saw ‘Matilda’ 50 times. Luckily, it’s a great show. She gave the last performance of ‘Matilda.’ I found it very stressful. It was all the anxiety of performing but none of the release. It’s like watching your heart outside your body.”

Continue reading the main story

In the meantime, his oldest son, Sam, has acted in a few TV shows. “It’s everything I said would never happen to my children, and now here I am,” Mr. McCarthy said.

Recently Sam was cast in the indie movie “All These Small Moments.” His mother will be played by Molly Ringwald, Mr. McCarthy’s co-star in “Pretty in Pink.”

“After the first day of rehearsal, Molly emailed me and said, ‘Your son just walked away from me and it was like watching you walk away from me 30 years ago,’” he said. “It was very sweet.”

As Mr. McCarthy posed for a photograph under a bridge, a woman of a certain vintage called out, “I just have to say — a lifetime! You look great.”

Continue reading the main story

He stared serenely into the distance.

Continue reading the main story

The post Andrew McCarthy’s Newest Role: Young Adult Novelist appeared first on Art of Conversation.

2017 April PAD Challenge: Day 2

This content was originally published by Robert Lee Brewer on 2 April 2017 | 6:00 am.

Source link

Okay, the first day is in the books, and it was a lot of fun. But we’ve got plenty of poeming left to go.

For today’s prompt, write a “not today” poem. Maybe it’s normal to give in to outside pressures, but not today. Or maybe you’re usually very disciplined in your health and wellness habits, but not today. Or maybe you struggle to write poems, but not today.

*****

The 2017 Poet’s Market, edited by Robert Lee Brewer, includes hundreds of poetry markets, including listings for poetry publications, publishers, contests, and more! With names, contact information, and submission tips, poets can find the right markets for their poetry and achieve more publication success than ever before.

In addition to the listings, there are articles on the craft, business, and promotion of poetry–so that poets can learn the ins and outs of writing poetry and seeking publication. Plus, it includes a one-year subscription to the poetry-related information on WritersMarket.com.. All in all, it’s the best resource for poets looking to secure publication.

*****

Here’s my attempt at a Not Today Poem:

“when you say we’ll see”

i see exactly what i want

being hoisted high above me

& know it won’t happen today

because “we’ll see” is code

for “maybe” which is code

for “when hell freezes over”

so we’ll see i guess we’ll see

& in the meantime i’ll plot out

my moves toward plan b

*****

Robert Lee Brewer is Senior Content Editor of the Writer’s Digest Writing Community and author of Solving the World’s Problems (Press 53). He always has a plan b and probably says, “We’ll see,” a little too frequently.

Follow him on Twitter @RobertLeeBrewer.

*****

Find more poetic posts here:

You might also like:

The post 2017 April PAD Challenge: Day 2 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Nonfiction: How the Courts Got Between Our Sheets

This content was originally published by MICHAEL KINSLEY on 31 March 2017 | 9:00 am.

Source link

“Sex and the Constitution” by Geoffrey R. Stone is a book on courts and sexual privacy that ranges across centuries.

Source link

The post Nonfiction: How the Courts Got Between Our Sheets appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Poet Who Stirred a Generation of Soviets, Dies at 83

This content was originally published by RAYMOND H. ANDERSON on 2 April 2017 | 12:47 am.

Source link

But it was as a tall, athletic young Siberian with a spirit both hauntingly poetic and fiercely political that he established his name in 20th-century literature. He was the best known of a small group of rebel poets and writers who brought hope to a young generation with poetry that took on totalitarian leaders, ideological zealots and timid bureaucrats. Among the others were Andrei Voznesensky, Robert Rozhdestvensky and Bella Akhmadulina, Mr. Yevtushenko’s first wife.

Continue reading the main story

But Mr. Yevtushenko did so working mostly within the system, taking care not to join the ranks of outright literary dissidents. By stopping short of the line between defiance and resistance, he enjoyed a measure of official approval that more daring dissidents came to resent.

While they were subjected to exile or labor camps, Mr. Yevtushenko was given state awards, his books were regularly published, and he was allowed to travel abroad, becoming an international literary superstar.

Some critics had doubts about his sincerity as a foe of tyranny. Some called him a sellout. A few enemies even suggested that he was merely posing as a protester to serve the security police or the Communist authorities. The exiled poet Joseph Brodsky once said of Mr. Yevtushenko, “He throws stones only in directions that are officially sanctioned and approved.”

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Yevtushenko’s defenders bristled at such attacks, pointing out how much he did to oppose the Stalin legacy, an animus fueled by the knowledge that both of his grandfathers had perished in Stalin’s purges of the 1930s. He was expelled from his university in 1956 for joining the defense of a banned novel, Vladimir Dudintsev’s “Not by Bread Alone.” He refused to join in the official campaign against Boris Pasternak, the author of “Doctor Zhivago” and the recipient of the 1958 Nobel Prize in Literature. Mr. Yevtushenko denounced the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968; interceded with the K.G.B. chief, Yuri V. Andropov, on behalf of another Nobel laureate, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn; and opposed the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

Photo

Mr. Yevtushenko in January 1972 during a news conference at Kennedy Airport in New York before a four-week tour of readings.

Credit

Dave Pickoff/Associated Press

Mr. Yevtushenko wrote thousands of poems, including some shallow ones that he dashed off, he admitted, just to mark an occasion. Some critics questioned the literary quality of his work. Some writers resented his flamboyance, sartorial and otherwise, and his success. But his foes as well as his friends agreed that a select few of his poems have entered the annals of Russian literature as masterpieces of insight and conscience.

Continue reading the main story

Written and read to crowds at critical moments, Yevtushenko poems like “Stalin’s Heirs” caught the spirit of a nation at a crossroads. In Russia, writers could be more influential at times than politicians. But they could also be severely rebuffed if they offended, as Pasternak did with his novel “Doctor Zhivago” and Solzhenitsyn did with “The Gulag Archipelago” and other works.

Combating Anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism lingered in the Kremlin after Stalin’s death. In one instance, nervous officials thwarted efforts to raise a monument at Babi Yar, a ravine near Kiev, Ukraine, where thousands of Jews were machine-gunned and buried in a mass grave in 1941 by the invading Germans.

Continue reading the main story

The reason the Kremlin said it resisted a memorial was that the Germans had shot other people there, too, not only Jews. Mr. Yevtushenko tackled the issue in 1961 in blunt verse that stunned many Russians and earned him acclaim around the world. The poem “Babi Yar,” composed after a haunting visit to the ravine, included these lines:

There are no monuments over Babi Yar.

But the sheer cliff is like a rough tombstone.

It horrifies me.

Today, I am as old

As the Jewish people.

It seems to me now,

That I, too, am a Jew.

Continue reading the main story

Alluding to the pogroms that erupted at intervals over the centuries, Mr. Yevtushenko went on:

It seems to me,

I am a boy in Byelostok.

Blood is flowing,

Spreading across the floors.

The leaders of the tavern mob are raging

And they stink of vodka and onions.

Kicked aside by a boot, I lie helpless.

In vain I plead with the brutes

As voices roar:

“Kill the Jews! Save Russia!”

Continue reading the main story

In a country ruled by Marxist myth, ostensibly free of bigotry, “Babi Yar” touched nerves in the leadership, and it was amended to meet official objections. Even so, it moved audiences. Whenever Mr. Yevtushenko recited the poem at public rallies, it was met with stunned silence and then thunderous ovations. He wrote once that he had received 20,000 letters hailing “Babi Yar.” Dmitri Shostakovich composed his Thirteenth Symphony on lines from that and other Yevtushenko poems.

But Mr. Yevtushenko was not allowed to give a public reading of the poem in Ukraine until the 1980s.

“Stalin’s Heirs,” published in 1962, also stirred Russians, appearing at a time when they feared that Stalinist-style repression might return to the country. It was published only after Nikita S. Khrushchev, the semi-liberal party leader who was then involved in a power struggle with conservatives, intervened as he pushed his cultural “thaw.” Stalin had been condemned anew the year before as having been a mad tyrant. The poem appeared in Pravda, the Communist Party’s official newspaper, and caused a sensation.

Continue reading the main story

“Stalin’s Heirs” opens with a description of Stalin’s body being borne in his coffin out of the Red Square mausoleum to a grave near the Kremlin wall.

Sullenly clenching

His embalmed fists,

He peered through a crack,

Just pretending to be dead.

He wanted to remember all those

Who carried him out.

Mr. Yevtushenko went on:

I turn to our government with a plea:

To double,

And triple the guard at the grave site

So Stalin does not rise again,

And with Stalin, the past.

And later, the main point of the poem:

We removed

Him

From the mausoleum.

But how do we remove Stalin

From Stalin’s heirs?

By the time democratic changes brought down Soviet Communist rule early in the 1990s, Mr. Yevtushenko had risen in the reform system to become a member of Parliament and secretary of the official Union of Soviet Writers. Along the way he received high honors, was published in the best periodicals and was sent abroad as an envoy of good will. He also endured abuse, jealousy, frustration and censorship. He once joked that Moscow censors were his best readers, the most expert at catching his meanings and nuances.

Photo

Mr. Yevtushenko at the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem in November 2007.

Mr. Yevtushenko at the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem in November 2007.Credit

Gil Cohen Magen/Reuters

Continue reading the main story

Evolution of an Artist

Yevgeny Aleksandrovich Gangnus was born on July 18, 1933, in Zima Junction, a remote lumber station on the trans-Siberian Railway in the Irkutsk region of Siberia, near Lake Baikal. His father, Aleksandr Rudolfovich Gangnus, was a geologist, as was his mother, Zinaida Ermolaevna Evtushenko, who became a singer. His parents divorced, and the boy took his mother’s surname. Yevgeny spent his early childhood years with his mother in Moscow. When German troops approached Moscow in late 1941, the family was evacuated to Zima and stayed there until 1944.

Continue reading the main story

While growing up, Yevgeny accompanied his father on geology expeditions to wild regions of Kazakhstan and the Altai Mountains, where his father recited poetry to him. The boy learned to love nature and literature.

He was also drawn to sports. At 16 he was selected to join a professional soccer team. But sudden literary success compelled him to abandon that ambition. Soon his poems began appearing in newspapers, popular magazines and literary monthlies. The authorities praised his early poems, which he later called “hack work,” and he was admitted to the elite Gorky Literary Institute and to the Soviet Writers’ Union.

Continue reading the main story

But after Stalin’s death — Mr. Yevtushenko was almost crushed to death in a funeral stampede in Moscow — his work began to run counter to Soviet Realism, the officially sanctioned artistic style, reflecting instead new thinking about individual responsibility and the state.

Themes of state repression and fear had recurred in his work over the years, but he also began introducing personal matters into his work, as he did in his long poem “Zima Junction,” about a return to his hometown in 1953. Published in 1956, it was followed by more volumes of poetry that refused to conform to the approved modes of expression. After he praised “Not by Bread Alone,” Dudintsev’s caustic 1956 novel about Soviet life, Mr. Yevtushenko was expelled from the Literary Institute.

Continue reading the main story

But as the 1950s grew to a close, he had published seven volumes of poetry and was allowed to read his work abroad. In the next few years he became familiar to literary circles in Eastern and Western Europe, the United States, Cuba, East Africa and Australia. Indeed, a virtual cult began to develop around him after Time magazine put his portrait, as an “angry young man,” on its cover in April 1962 and printed a laudatory article about him as a leading spirit in a changing, liberalizing Russia.

Continue reading the main story

The post Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Poet Who Stirred a Generation of Soviets, Dies at 83 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

April 1, 2017

Richard Bolles, Who Wrote ‘What Color Is Your Parachute?,’ Dies at 90

This content was originally published by PAUL VITELLO on 2 April 2017 | 1:30 am.

Source link

It also found a fan base among job-seekers attracted to Mr. Bolles’s homespun style — a fusion of boot camp rigor (job-hunters should spend at least 40 hours a week hunting), practical advice (“If you’re being interviewed over lunch, never — never — order a drink ... Don’t ... do ... it! ... Even if they do it”) and muted spirituality.

Continue reading the main story

Job-hunting was an art form, more like dating than like selling a used car, he told readers. “You may never understand why things sometimes work, and sometimes don’t,” he wrote.

With that in mind, Mr. Bolles said, “What Color Is Your Parachute?,” subtitled “A Practical Manual for Job-Hunters and Career Changers,” was framed less as a guide to the job market than as a guide to help readers understand themselves — to help them figure out what they really liked doing so that they could find the job that would let them do it.

“You need firm ground to stand on,” Mr. Bolles told an interviewer in 2000. “From there you can deal with the change.”

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Bolles, an ordained Episcopalian priest until 2004, when he left the ministry, said the title of his book came from an oft-repeated discussion he had in the 1960s with parishioners who were unhappy in their jobs. They would say they were thinking of bailing out. “And I always thought of an airplane when I heard that phrase,” he said. “So I would respond, ‘What color is your parachute?’”

“Parachute” climbed book-sales rankings slowly but steadily throughout the decade. In 1979, it reached the New York Times best-seller list, where it remained for more than a decade, returning intermittently for years afterward.

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Bolles was well qualified to write a handbook on changing direction; he had changed his own several times, from planning a career in the chemical industry to becoming a minister and then experiencing being fired, at 41, and enduring the anxiety of unemployment at a time when he and his wife then, the former Janet Price, had four small children.

It had never entered his mind, though, that he would write a blockbuster. “I was just trying to help people be better prepared than I was when I was fired and started looking for a job,” he said in an interview for this obituary in 2014.

Photo

Mr. Bolles said in 2014 that he hoped his franchise would continue after he was gone and that his son Gary had asked him about updating future editions of “What Color Is Your Parachute?”

Credit

Sonny Figueroa/The New York Times

Continue reading the main story

Yet whether he knew it or not, Mr. Bolles had anticipated a sea change in the relationship between workers and employers in the United States, said Micki McGee, an associate professor of sociology at Fordham University and the author of “Self-Help, Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life,” a 2005 examination of self-help literature that includes a close analysis of Mr. Bolles’s book.

Continue reading the main story

She said “Parachute” had come along right at the beginning of a historic shift, when corporate strategies like outsourcing, subcontracting, downsizing and mergers were starting to erode traditional notions of job security. The idea that you could stay in one job for a lifetime began coming undone in the early 1970s, and “Parachute’s” perennial sales reflected, at least in part, this new reality.

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Bolles said he had come to acknowledge that connection over time, but, he added wryly, the success of “Parachute” had also reflected the fact that it was a pretty good book.

Richard Nelson Bolles was born March 19, 1927, in Milwaukee, the first of three children of Donald Clinton Bolles, an editor for The Associated Press, and the former Frances Fifield, a homemaker.

His brother, Donald Jr., who followed his father into journalism, was killed in 1976 in Phoenix when a bomb detonated under his car. Donald Bolles Jr. was then working as an investigative reporter for The Arizona Republic, and the killing was widely believed to be linked to a series of exposés he had been writing about corporate and organized crime in the state. The assassination resulted in the prosecution of one person but remained largely unsolved.

Continue reading the main story

After serving in the Navy at the tail end of World War II, Richard Bolles studied chemical engineering for two years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then transferred to Harvard, where he earned his bachelor’s degree cum laude with a major in physics. While still an undergraduate, he was moved by a sermon he heard one Sunday at church about a critical shortage of ministers. After graduation, instead of accepting a lucrative job offer in the chemical industry, he decided to become an Episcopal priest.

He attended General Theological Seminary in New York, where he received a master’s degree in New Testament studies and was ordained in 1953. He served as a rector at several churches in northern New Jersey, including St. John’s in Passaic, where he often counseled teenagers on sex and drug use. After participating in the 1963 March on Washington led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., he reached out to an all-black church in Passaic and, with its pastor, the Rev. Avery Johnson, led the integration of their churches, despite the opposition of some parishioners.

Mr. Bolles had been a clergyman for 18 years when a combination of budget problems and philosophical differences with superiors led to the elimination of his job and his dismissal in 1968 as a pastor at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, the flagship church of the Episcopal Diocese of California.

After six months of anxious searching, he landed a job in 1969 with United Ministries in Higher Education, an interdenominational church organization that had long been involved in recruiting and supporting college chaplains across the country. But college chaplains were increasingly being laid off, leaving Mr. Bolles a new mission: to help chaplains at campuses in seven Western states find new careers.

Continue reading the main story

That effort led him into research that inspired him to write the how-to manual that evolved into “What Color Is Your Parachute?” Among his other books was “The Three Boxes of Life and How to Get Out of Them,” on balancing work and personal life.

Continue reading the main story

Besides his son Gary, he is survived by his second wife of more than 12 years, Marci Mendoza Bolles; two other children from his first marriage, Stephen and Sharon Bolles; and 10 grandchildren. A third son, Mark, died in 2012.

In the 2014 interview, Mr. Bolles said he hoped his franchise would continue after he was gone. His son Gary, he said, had asked him about updating future editions of “Parachute” and finding other job-counseling experts who might provide new advice.

Continue reading the main story

“I told him to make sure to find people who were funny, have a lightheartedness about them,” Mr. Bolles said. “When you are out of work and on the ropes, that is so important.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Richard Bolles, Who Wrote ‘What Color Is Your Parachute?,’ Dies at 90 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

World War II Fiction: The Home Front

This content was originally published by MARY POLS on 31 March 2017 | 10:00 am.

Source link

Shattuck’s characters represent the range of responses to fascism. Her achievement — beyond unfolding a plot that surprises and devastates — is in her subtle exploration of what a moral righteousness like Marianne’s looks like in the aftermath of war, when communities and lives must be rebuilt, together.

Continue reading the main story

THE CHILBURY LADIES’ CHOIR

By Jennifer Ryan

371 pp. Crown, $26.

Photo

Ryan’s first novel represents the sunnier side of World War II fiction, where women stand up for one another, frolic with whatever stray men are still about (dashing, flat-footed and otherwise) and solve a few mysteries. The empowerment is genteel. In Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows’s “The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society,” such ladies (and a few gentlemen) tackled literature. Here they take up singing.

Although the vicar has put the village choir on hiatus until the men return, Miss Primrose Trent, a music tutor from the local university who is prone to sweeping into rooms majestically (a role made for Emma Thompson), announces that the women will form their own singing group. Plotwise, a carrot in the form of a public choir competition is dangled, but the narrative is driven by the ladies’ reconsideration of their own worth, whether over- or underinflated.

Set during six months in 1940, the story unfolds mostly in letters and journal entries from nearly a dozen vantage points. Four dominate: Mrs. Margaret Tilling, a middle-aged widow about to send her only child off to the front; Edwina Paltry, a midwife of suspect ethical standards; and to-the-manor-born sisters, Kitty Winthrop, 13, and minxlike Venetia, 18, whose brother has just been killed in a submarine explosion. Dry your eyes: “He was a disgusting bully,” Kitty writes in her diary.

Continue reading the main story

This death sets in play a baby-swapping plot hatched by the Brigadier, Kitty and Venetia’s mustache-twiddling father, who needs a male heir. It’s all quite diverting, even if Ryan sometimes seems more interested in describing her characters’ clothing than their inner lives (skirt-swishing Venetia is a veritable Carmen Miranda). As for the war itself, it’s mostly a narrative convenience, a way to get rid of supporting characters we’re merely fond of, including one whose demise, while sad, neatly solves a dilemma. World War II is a way to tame a shrew and a bully and to pair off adorable couples of multiple generations. The fact that the fighting is still going strong at the book’s end confirms that this isn’t a story about war in any real sense, but rather a novel set in a time of war. To a tune called pleasing.

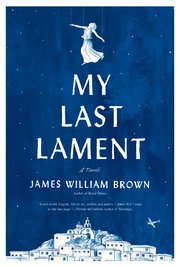

MY LAST LAMENT

By James William Brown

341 pp. Berkley, $26.

Photo

An American scholar travels to a Greek village to interview a woman named Aliki, its last professional lamenter, a composer of poems for the dead. Due to her reticence and some technical difficulties, the visit is a failure, so the American leaves behind a tape recorder, hoping Aliki will record herself when she’s in “the right frame of mind.” The elderly Luddite does a lot of precious fumbling (“Now let me see, how do I turn this thing on?”) before delivering a very personal lament, one big enough to fill six cassettes — less poem than novel.

Continue reading the main story

At 14, Aliki saw her father executed by the occupying Nazis and was rendered mute. Another act of violence brings back her voice; in a sense, she’s shocked into her professional calling. When the Nazis clear out, she and two other children, a Jewish teenager named Stelios, who had been hiding in her village, and an orphaned 11-year-old boy, Takis, set off on an odyssey around Greece, looking for everything from food to a more viable future.

Brown struggles to make his characters entirely plausible, sporadically resorting to jarringly modern language. “It was only after the Germans came,” Aliki says, sounding as if she’s chit-chatting after yoga class, “that the — I don’t know what — the glow just went out of everything.” And yet there’s a lot to hold one’s attention: The Greek setting is far less traveled ground in the English-language World War II novel, and Brown’s pacing is strong and engaging, at least at the outset.

The children become street performers of folkloric shadow puppetry, eventually traveling to Crete looking for paying audiences. This is when Brown loses narrative control, bogging down in an account of their journeys through the violent times that followed the war. There’s a love story, but what stays with you at the end of this ambitious but unruly narrative is Takis, Aliki’s orphan companion. Brown veers between making him the creepy child right out of a horror movie and the touchingly misunderstood victim of mental illness or post-traumatic stress. There are good larger points to be made here — about assigning blame in wartime and what it means to soldier on under deeper burdens than immediate circumstances, however awful. But, like Aliki with the cassette recorder, Brown fumbles when he sets his hand to them.

Continue reading the main story

The post World War II Fiction: The Home Front appeared first on Art of Conversation.